|

|

|

WILLIAM PAULET, PAWLET, or POULET, first Marquis of Winchester (1485?-1572), was eldest son of Sir John Paulet

of Basing, near Basingstoke in Hampshire, the head of a younger branch of an ancient Somerset family seated in the

fourteenth century at Pawlet or Paulet and Road, close to Bridgwater.1 William's great-grandfather acquired

the Hampshire estates by his marriage with Constance, granddaughter and coheiress of Thomas Poynings, baron St. John

of Basing (d. 1428). Hinton St. George, near Crewkerne, became from the middle of the fifteenth century the chief

residence of the elder branch, to which belong Sir Amias Paulet and the present Earl Poulett.2

Paulet's father held a command against the Cornish rebels in 1497 [see Battle of Blackheath],

and died after 1519.3 His monument remains in Basing church. He married his cousin Alice (or Elizabeth?),

daughter of Sir William Paulet, the first holder of Hinton St. George.4 William, their eldest son, was born,

according to Doyle (Official Baronage), in 1485; Brooke, followed by Dugdale, says 1483; while Camden asserts

that he was ninety-seven at his death, which would place his birth in 1474 or 1475.

Paulet was sheriff of Hampshire in 1512, 1519, 1523, and again in 1527.5 Knighted before the end of 1525,

he was appointed master of the king's wards in November of the next year with Thomas Englefield.6 He appears

in the privy council in the same year.7 In the Reformation parliament of 1529-36 he sat as knight of the

shire for Hampshire. Created 'surveyor of the king's widows and governor of all idiots and naturals in the king's hands'

in 1531, he became comptroller of the royal household in May 1532, and a few mouths later joint-master of the royal

woods with Thomas Cromwell.8 Now or later he held the offices of high steward

of St. Swithin's Priory, Winchester, steward of Shene Priory, Dorset, and keeper (1536) of Pamber Forest, near

Basingstoke.9

In the summer of 1533 Paulet went to France as a member of the embassy which the Duke of Norfolk

took over to join Francis I in a proposed interview with the pope, and kept Cromwell informed

of its progress. But Clement's fulmination against the divorce pronounced by

Cranmer caused their recall.10 On his return

he was charged with the unpleasant task of notifying the king's orders to his discarded wife [Catherine

of Aragon] and daughter [Princess, later Queen, Mary]. He was one of the judges of

Fisher and More

in the summer of 1535, and of Anne Boleyn's supposed accomplices in May 1536.

When the pilgrimage of grace broke out in the autumn, Paulet took joint charge of the

musters of the royal forces, and himself raised two hundred men. The rebels complaining of the exclusion of noblemen from

the king's council, Henry reminded them of the presence of Paulet and others.11 In carrying out his royal master's

commands he was not, it would appear, unnecessarily harsh. Anne Boleyn excepted him from her

complaints against the council; 'the controller,' she admitted,' was a very gentleman.'12

His services did not go unrewarded. The king visited his 'poor house' at Basing in October 1536.13 The site and

other possessions of Netley Abbey, near Southampton, were granted to him in August 1536.14 He acted as treasurer

of the household from October 1537 to March 1539, when the old St. John peerage was recreated in his favour, but without

the designation 'of Basing'.15

The new peer became the first master of

Henry VIII's Court of Wards and Liveries in 1540, Knight of the Garter

in 1543 (April), and, two years later, governor of Portsmouth. Appointed Lord Chamberlain of the Household in May 1543, he was

great master (i.e. lord steward) of the same from 1545 to 1550.16 A year before the king's death he became

lord president of the council, and was nominated in Henry's will one of the eighteen executors who were to act as a council of

regency during his son's minority.

The new peer became the first master of

Henry VIII's Court of Wards and Liveries in 1540, Knight of the Garter

in 1543 (April), and, two years later, governor of Portsmouth. Appointed Lord Chamberlain of the Household in May 1543, he was

great master (i.e. lord steward) of the same from 1545 to 1550.16 A year before the king's death he became

lord president of the council, and was nominated in Henry's will one of the eighteen executors who were to act as a council of

regency during his son's minority.

Under Somerset, St. John was for a few months in 1547 keeper of the great seal. He joined in

overthrowing the protector [i.e. Somerset], and, five days after parliament had deposed Somerset, was created (19 Jan. 1550)

earl of Wiltshire, in which county he had estates.17 The white staff laid down by Somerset was given to the new earl,

who contrived to remain lord treasurer until his death, twenty-two years later. Warwick succeeded

to his old offices of great master of the household and lord president of the council.18 Though Wiltshire was not, like

Northampton and Herbert, prominently identified with Warwick, he

received a further advance in the peerage on the final fall of Somerset. On 11 Oct. 1551, the same day that Warwick became duke of

Northumberland, he was created marquis of Winchester.19 Six weeks later he acted as lord steward at the trial of Somerset.

Careful as Winchester was to trim his sails to the prevailing wind, the protestants did not trust him. Knox,

unless he exaggerates, boldly denounced him in his last sermon before Edward VI as the 'crafty fox

Shebna unto good King Ezekias sometime comptroller and then treasurer.'20 Northumberland and Winchester, Knox tells us,

ruled all the court, the former by stout courage and proudness of stomach, the latter by counsel and wit. Though the reformers

considered him a papist, Winchester did not scruple to take out a license for himself, his wife, and twelve friends to eat flesh in

Lent and on fast days.21 Knox did him an injustice when he accused him of having been a prime party to Northumberland's

attempt to change the order of the succession. He was, on the contrary, strongly opposed to it: and even after he had bent, like

others, before the imperious will of the duke, and signed the letters patent of 21 June 1553, he did not cease to urge in the council

the superior claim of the original act of succession.22

After the death of the young king and the proclamation of Queen Jane, Winchester delivered the crown

jewels to the latter on 12 July. According to the Venetian Badoaro, he made her very indignant by informing her of Northumberland's

intention to have her husband crowned as well.23 But Winchester and several other lords were only waiting until they could

safely turn against the duke. The day after he left London to bring in Mary (15 July) they made a vain

attempt to get away from the Tower, where they were watched by the garrison Northumberland had placed there; Winchester made an excuse

to go to his house, but was sent for and brought back at midnight.

On the 19th, however, after the arrival of news of Northumberland's ill-success, the lords contrived to get away to Baynard's Castle,

and, after a brief deliberation, proclaimed Queen Mary. She confirmed him in all his offices, to which in

March 1556 that of lord privy seal was added, and thoroughly appreciated his care and vigilance in the management of her exchequer. He

gave a general support to Gardiner in the House of Lords, and did not refuse to convey

Elizabeth to the Tower. It was Sussex,

however, and not he, who generously took the risk of giving her time to make a last appeal to her sister.24 So firmly was

Winchester convinced of the impolicy of her Spanish marriage, that even after it was approved he was heard to swear that he would set

upon Philip when he landed.25 But he was rapidly brought to acquiesce in its accomplishment, and

entertained Philip and Mary at Basing on the day after their wedding.

On Mary's death Winchester rode through London with the proclamation of her successor [Queen Elizabeth I],

and, in spite of his advanced age, obtained confirmation in the onerous office of treasurer, and acted as speaker of the House of Lords

in the parliaments of 1559 and 1566, showing no signs of diminished vigour. He voted in the small minority against any alteration of the

church services, but did not carry his opposition further; and Heath, Archbishop of York, and Thirlby, Bishop of Ely, were deprived at

his house in Austin Friars.26 For some years he was on excellent terms with Cecil, to whom he wrote,

after an English reverse before Leith in May 1560, that 'worldly things would sometimes fall out contrary, but if quietly taken could be

quietly amended.'27

Three months later, when the queen visited him at Basing, he sent the secretary warning against certain 'back counsels' about the queen.28

Elizabeth was so pleased with the good cheer he made her that she playfully lamented his great age, 'for, by my troth,' said she, 'if my

lord treasurer were but a young man, I could find it in my heart to have him for a husband before any man in England.'29 Two

years later, when she was believed to be dying, Winchester persuaded the council to agree to submit the rival claims to the succession to

the crown lawyers and judges, and to stand by their decision.30

He was opposed to all extremes. In 1561, when there was danger of a Spanish alliance to cover a union between the queen and

Dudley, he supported the counter-proposal of alliance with the French Calvinists, but seven years later he

deprecated any such championship of protestantism abroad as might lead to a breach with Spain, and recommended that the Duke of Alva

should be allowed to procure clothes and food for his soldiers in England, 'that he might be ready for her grace when he might do her

any service.'31 He disliked the turn Cecil was endeavouring to give to English policy, and he was

in sympathy with, if he was not a party to, the intrigues of 1569 against the secretary.32

Winchester was still in harness when he died, a very old man, at Basing House on 10 March 1572. His tomb remains on the south side of

the chancel of Basing church. Winchester was twice married, and lived to see 103 of his own descendants.33 His first wife

was Elizabeth (d. 25 Dec. 1568), daughter of Sir William Capel, lord mayor of London in 1503, by whom he had four sons — (1) John,

second marquis of Winchester; (2) Thomas; (3) Chediok, governor of Southampton under Mary and Elizabeth; (4) Giles — and four

daughters: Elizabeth, Margaret, Margerie, and Eleanor, the last of whom married Sir Richard Pecksall, master of the buckhounds, and

died on 26 Sept. 1558.34 By his second wife, Winifrid, daughter of Sir John Bruges, alderman of London, and widow of Sir

Richard Sackville, chancellor of the exchequer, he left no issue. She died in 1586.

Sir Robert Naunton, in his reminiscences of Elizabethan statesmen (he was nine years old at Winchester's death), reports that in his

old age he was quite frank with his intimates on the secret of the success with which he had weathered the revolutions of four reigns.

'Questioned how he had stood up for thirty years together amidst the changes and ruins of so many chancellors and great personages,

"Why," quoth the marquis, "ortus sum e salice non ex quercu."35 And truly it seems the old man had taught them all, especially

William, earl of Pembroke.'36

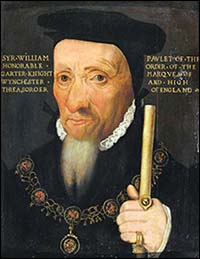

Winchester rebuilt Basing House, which he obtained license to fortify in 1531, on so princely a scale that, according to Camden, his

posterity were forced to pull down a part of it. An engraving of the mansion after the famous siege is given in Baigent (p. 428). The

marquis was one of those who sent out the expedition of Chancellor and Willoughby to northern seas in 1553, and became a member of the

Muscovy Company incorporated under Mary.37 A portrait by a painter unknown is engraved in Doyle's 'Official Baronage,' and

another, which represents him with the treasurer's white staff; in Walpole's edition of Naunton (p. 103), from a painting also, it would

seem, unassigned, in King's College, Cambridge. Two portraits are mentioned in the catalogue of the Tudor exhibition (Nos. 323, 348),

in both of which he grasps the white staff. If the latter, which is in the Duke of Northumberland's collection, is correctly described,

its ascription to Holbein must be erroneous, as he did not become treasurer until 1550, and the artist died in 1543.

1. Collinson, History of Somerset, ii. 166, iii. 74.

2. [i.e., "present" at the writing of this article in 1909; the last Earl Poulett died in 1973].

3. Cayley, Architectural Memoir of Old Basing Church, p. 10; cf. Baigent, History of Basingstoke, p. 19; Dugdale, Baronage, ii. 376.

4. cf. Notes and Queries, 5th ser. viii 135.

5. Calendar of Letters and Papers of the Reign of Henry VIII, ed. Brewer and Gairdner.

6. ib. iv. 2000, 2673.

7. ib. iv. 3096.

8. ib. v. 80, 1069, 1549.

9. ib. x. 392.

10. ib. vi. 391, 661, 830; The Chronicle of Calais, p. 44.

11. Letters and Papers, xi. 957, xii. pt. i. 1013.

12. ib. x. 797.

13. ib. ix. 639.

14. ib. xi. 385.

15. Courthope, Historic Peerage.

16. Machyn, Diary, p. xiv.

17. Froude, History of England, iv. 498.

18. Machyn, pp. xiv-xv.

19. Journal of Edward VI, p. 47; Calendar of State Papers, ed. Lemon, p. 35; Dugdale, followed by Courthope and Doyle, gives 12 Oct.

20. Strype, Memorials and Annals, Clarendon Press Ed. iv. 71.

21. Rymer's Foedera, xv. 329.

22. Froude, v. 162,168.

23. ib. v. 190.

24. ib. vi. 379.

25. Froude, v. 812.

26. ib. vi. 194; Machyn, p. 203.

27. Froude, vi. 370.

28. ib. vi. 413.

29. Strype, Annals, i. 367.

30. Froude, vi. 589.

31. ib. vi. 461, viii. 445.

32. Camden, Annales, p.151.

33. ibid.

34. Machyn, p. 307; Dugdale, ii. 377.

35. [trans. "I came of the willow, not of the oak."]

36. Fragmenta Regalia, p. 95.

37. Calendar of State Papers, ed. Lemon, p. 66; Strype, Memorials, v. 620.

Source:

Tait, James. "William Paulet, first Marquis of Winchester."

The Dictionary of National Biography. Vol XV. Sidney Lee, Ed.

New York: The Macmillan Co., 1909. 537-539.

| to Luminarium Encyclopedia |

Site ©1996-2023 Anniina Jokinen. All rights reserved.

This page was created on August 24, 2009. Last updated April 11, 2023.

|

Index of Encyclopedia Entries:

Medieval Cosmology

Prices of Items in Medieval England

Edward II

Isabella of France, Queen of England

Piers Gaveston

Thomas of Brotherton, E. of Norfolk

Edmund of Woodstock, E. of Kent

Thomas, Earl of Lancaster

Henry of Lancaster, Earl of Lancaster

Henry of Grosmont, Duke of Lancaster

Roger Mortimer, Earl of March

Hugh le Despenser the Younger

Bartholomew, Lord Burghersh, elder

Hundred Years' War (1337-1453)

Edward III

Philippa of Hainault, Queen of England

Edward, Black Prince of Wales

John of Eltham, Earl of Cornwall

The Battle of Crécy, 1346

The Siege of Calais, 1346-7

The Battle of Poitiers, 1356

Lionel of Antwerp, Duke of Clarence

John of Gaunt, Duke of Lancaster

Edmund of Langley, Duke of York

Thomas of Woodstock, Gloucester

Richard of York, E. of Cambridge

Richard Fitzalan, 3. Earl of Arundel

Roger Mortimer, 2nd Earl of March

The Good Parliament, 1376

Richard II

The Peasants' Revolt, 1381

Lords Appellant, 1388

Richard Fitzalan, 4. Earl of Arundel

Archbishop Thomas Arundel

Thomas de Beauchamp, E. Warwick

Robert de Vere, Earl of Oxford

Ralph Neville, E. of Westmorland

Thomas Mowbray, Duke of Norfolk

Edmund Mortimer, 3. Earl of March

Roger Mortimer, 4. Earl of March

John Holland, Duke of Exeter

Michael de la Pole, E. Suffolk

Hugh de Stafford, 2. E. Stafford

Henry IV

Edward, Duke of York

Edmund Mortimer, 5. Earl of March

Henry Percy, Earl of Northumberland

Sir Henry Percy, "Harry Hotspur"

Thomas Percy, Earl of Worcester

Owen Glendower

The Battle of Shrewsbury, 1403

Archbishop Richard Scrope

Thomas Mowbray, 3. E. Nottingham

John Mowbray, 2. Duke of Norfolk

Thomas Fitzalan, 5. Earl of Arundel

Henry V

Thomas, Duke of Clarence

John, Duke of Bedford

Humphrey, Duke of Gloucester

John Talbot, Earl of Shrewsbury

Richard, Earl of Cambridge

Henry, Baron Scrope of Masham

William de la Pole, Duke of Suffolk

Thomas Montacute, E. Salisbury

Richard Beauchamp, E. of Warwick

Henry Beauchamp, Duke of Warwick

Thomas Beaufort, Duke of Exeter

Cardinal Henry Beaufort

John Beaufort, Earl of Somerset

Sir John Fastolf

John Holland, 2. Duke of Exeter

Archbishop John Stafford

Archbishop John Kemp

Catherine of Valois

Owen Tudor

John Fitzalan, 7. Earl of Arundel

John, Lord Tiptoft

Charles VII, King of France

Joan of Arc

Louis XI, King of France

Charles the Bold, Duke of Burgundy

The Battle of Agincourt, 1415

The Battle of Castillon, 1453

The Wars of the Roses 1455-1485

Causes of the Wars of the Roses

The House of Lancaster

The House of York

The House of Beaufort

The House of Neville

The First Battle of St. Albans, 1455

The Battle of Blore Heath, 1459

The Rout of Ludford, 1459

The Battle of Northampton, 1460

The Battle of Wakefield, 1460

The Battle of Mortimer's Cross, 1461

The 2nd Battle of St. Albans, 1461

The Battle of Towton, 1461

The Battle of Hedgeley Moor, 1464

The Battle of Hexham, 1464

The Battle of Edgecote, 1469

The Battle of Losecoat Field, 1470

The Battle of Barnet, 1471

The Battle of Tewkesbury, 1471

The Treaty of Pecquigny, 1475

The Battle of Bosworth Field, 1485

The Battle of Stoke Field, 1487

Henry VI

Margaret of Anjou

Richard Plantagenet, Duke of York

Edward IV

Elizabeth Woodville

Richard Woodville, 1. Earl Rivers

Anthony Woodville, 2. Earl Rivers

Jane Shore

Edward V

Richard III

George, Duke of Clarence

Ralph Neville, 2. Earl of Westmorland

Richard Neville, Earl of Salisbury

Richard Neville, Earl of Warwick

Edward Neville, Baron Bergavenny

William Neville, Lord Fauconberg

Robert Neville, Bishop of Salisbury

John Neville, Marquis of Montagu

George Neville, Archbishop of York

John Beaufort, 1. Duke Somerset

Edmund Beaufort, 2. Duke Somerset

Henry Beaufort, 3. Duke of Somerset

Edmund Beaufort, 4. Duke Somerset

Margaret Beaufort

Edmund Tudor, Earl of Richmond

Jasper Tudor, Earl of Pembroke

Humphrey Stafford, D. Buckingham

Henry Stafford, Duke of Buckingham

Humphrey Stafford, E. of Devon

Thomas, Lord Stanley, Earl of Derby

Sir William Stanley

Archbishop Thomas Bourchier

Henry Bourchier, Earl of Essex

John Mowbray, 3. Duke of Norfolk

John Mowbray, 4. Duke of Norfolk

John Howard, Duke of Norfolk

Henry Percy, 2. E. Northumberland

Henry Percy, 3. E. Northumberland

Henry Percy, 4. E. Northumberland

William, Lord Hastings

Henry Holland, Duke of Exeter

William Fitzalan, Earl of Arundel

William Herbert, 1. Earl of Pembroke

John de Vere, 12th Earl of Oxford

John de Vere, 13th Earl of Oxford

Thomas de Clifford, 8. Baron Clifford

John de Clifford, 9. Baron Clifford

John Tiptoft, Earl of Worcester

Thomas Grey, 1. Marquis Dorset

Sir Andrew Trollop

Archbishop John Morton

Edward Plantagenet, E. of Warwick

John Talbot, 2. E. Shrewsbury

John Talbot, 3. E. Shrewsbury

John de la Pole, 2. Duke of Suffolk

John de la Pole, E. of Lincoln

Edmund de la Pole, E. of Suffolk

Richard de la Pole

John Sutton, Baron Dudley

James Butler, 5. Earl of Ormonde

Sir James Tyrell

Edmund Grey, first Earl of Kent

George Grey, 2nd Earl of Kent

John, 5th Baron Scrope of Bolton

James Touchet, 7th Baron Audley

Walter Blount, Lord Mountjoy

Robert Hungerford, Lord Moleyns

Thomas, Lord Scales

John, Lord Lovel and Holand

Francis Lovell, Viscount Lovell

Sir Richard Ratcliffe

William Catesby

Ralph, 4th Lord Cromwell

Jack Cade's Rebellion, 1450

Tudor Period

King Henry VII

Queen Elizabeth of York

Arthur, Prince of Wales

Lambert Simnel

Perkin Warbeck

The Battle of Blackheath, 1497

King Ferdinand II of Aragon

Queen Isabella of Castile

Maximilian I, Holy Roman Emperor

King Henry VIII

Queen Catherine of Aragon

Queen Anne Boleyn

Queen Jane Seymour

Queen Anne of Cleves

Queen Catherine Howard

Queen Katherine Parr

King Edward VI

Queen Mary I

Queen Elizabeth I

Henry Fitzroy, Duke of Richmond

Margaret Tudor, Queen of Scotland

James IV, King of Scotland

The Battle of Flodden Field, 1513

James V, King of Scotland

Mary of Guise, Queen of Scotland

Mary Tudor, Queen of France

Louis XII, King of France

Francis I, King of France

The Battle of the Spurs, 1513

Field of the Cloth of Gold, 1520

Charles V, Holy Roman Emperor

Eustace Chapuys, Imperial Ambassador

The Siege of Boulogne, 1544

Cardinal Thomas Wolsey

Archbishop Thomas Cranmer

Thomas Cromwell, Earl of Essex

Thomas, Lord Audley

Thomas Wriothesley, E. Southampton

Sir Richard Rich

Edward Stafford, D. of Buckingham

Thomas Howard, 2nd Duke of Norfolk

Thomas Howard, 3rd Duke of Norfolk

John Dudley, Duke of Northumberland

Charles Brandon, Duke of Suffolk

Thomas Boleyn, Earl of Wiltshire

George Boleyn, Viscount Rochford

John Russell, Earl of Bedford

Thomas Grey, 2. Marquis of Dorset

Henry Grey, D. of Suffolk

Charles Somerset, Earl of Worcester

George Talbot, 4. E. Shrewsbury

Francis Talbot, 5. E. Shrewsbury

Henry Algernon Percy,

5th Earl of Northumberland

Henry Algernon Percy,

6th Earl of Northumberland

Ralph Neville, 4. E. Westmorland

Henry Neville, 5. E. Westmorland

William Paulet, Marquis of Winchester

Sir Francis Bryan

Sir Nicholas Carew

John de Vere, 15th Earl of Oxford

John de Vere, 16th Earl of Oxford

Thomas Seymour, Lord Admiral

Edward Seymour, Protector Somerset

Margaret Pole, Countess of Salisbury

Henry Pole, Lord Montague

Sir Geoffrey Pole

Thomas Manners, Earl of Rutland

Henry Manners, Earl of Rutland

Henry Bourchier, 2. Earl of Essex

Robert Radcliffe, 1. Earl of Sussex

Henry Radcliffe, 2. Earl of Sussex

George Hastings, Earl of Huntingdon

Henry Courtenay, Marquis of Exeter

George Neville, Baron Bergavenny

Sir Edward Neville

William, Lord Paget

William Sandys, Baron Sandys

William Fitzwilliam, E. Southampton

Sir Anthony Browne

Sir Thomas Wriothesley

Sir William Kingston

George Brooke, Lord Cobham

Sir Richard Southwell

Thomas Fiennes, 9th Lord Dacre

Sir Francis Weston

Henry Norris

Lady Jane Grey

Sir Thomas Arundel

Sir Richard Sackville

Sir William Petre

Sir John Cheke

Walter Haddon, L.L.D

Sir Peter Carew

Sir John Mason

Nicholas Wotton

John Taylor

Sir Thomas Wyatt, the Younger

Cardinal Lorenzo Campeggio

Cardinal Reginald Pole

Stephen Gardiner, Bishop of Winchester

Edmund Bonner, Bishop of London

Nicholas Ridley, Bishop of London

John Hooper, Bishop of Gloucester

John Aylmer, Bishop of London

Thomas Linacre

William Grocyn

Archbishop William Warham

Cuthbert Tunstall, Bishop of Durham

Richard Fox, Bishop of Winchester

Edward Fox, Bishop of Hereford

Pope Julius II

Pope Leo X

Pope Clement VII

Pope Paul III

Pope Pius V

Pico della Mirandola

Desiderius Erasmus

Martin Bucer

Richard Pace

Christopher Saint-German

Thomas Tallis

Elizabeth Barton, the Nun of Kent

Hans Holbein, the Younger

The Sweating Sickness

Dissolution of the Monasteries

Pilgrimage of Grace, 1536

Robert Aske

Anne Askew

Lord Thomas Darcy

Sir Robert Constable

Oath of Supremacy

The Act of Supremacy, 1534

The First Act of Succession, 1534

The Third Act of Succession, 1544

The Ten Articles, 1536

The Six Articles, 1539

The Second Statute of Repeal, 1555

The Act of Supremacy, 1559

Articles Touching Preachers, 1583

Queen Elizabeth I

William Cecil, Lord Burghley

Robert Cecil, 1st Earl of Salisbury

Sir Francis Walsingham

Sir Nicholas Bacon

Sir Thomas Bromley

Robert Dudley, Earl of Leicester

Ambrose Dudley, Earl of Warwick

Henry Carey, Lord Hunsdon

Sir Thomas Egerton, Viscount Brackley

Sir Francis Knollys

Katherine "Kat" Ashley

Lettice Knollys, Countess of Leicester

George Talbot, 6. E. of Shrewsbury

Elizabeth, Countess of Shrewsbury

Gilbert Talbot, 7. E. of Shrewsbury

Sir Henry Sidney

Sir Robert Sidney

Archbishop Matthew Parker

Walter Devereux, 1st Earl of Essex

Robert Devereux, 2nd Earl of Essex

Penelope Devereux, Lady Rich

Sir Christopher Hatton

Edward Courtenay, E. Devonshire

Edward Manners, 3rd Earl of Rutland

Thomas Radcliffe, 3. Earl of Sussex

Henry Radcliffe, 4. Earl of Sussex

Robert Radcliffe, 5. Earl of Sussex

William Parr, Marquis of Northampton

Henry Wriothesley, 2. Southampton

Henry Wriothesley, 3. Southampton

Charles Neville, 6. E. Westmorland

Thomas Percy, 7. E. Northumberland

Henry Percy, 8. E. Northumberland

Henry Percy, 9. E. Nothumberland

William Herbert, 1. Earl of Pembroke

Charles, Lord Howard of Effingham

Thomas Howard, 4th Duke of Norfolk

Henry Howard, 1. Earl of Northampton

Thomas Howard, 1. Earl of Suffolk

Henry Hastings, 3. E. of Huntingdon

Edward Manners, 3rd Earl of Rutland

Roger Manners, 5th Earl of Rutland

Francis Manners, 6th Earl of Rutland

Henry FitzAlan, 12. Earl of Arundel

Thomas, Earl Arundell of Wardour

Edward Somerset, E. of Worcester

William Davison

Sir Walter Mildmay

Sir Ralph Sadler

Sir Amyas Paulet

Gilbert Gifford

Anthony Browne, Viscount Montague

François, Duke of Alençon & Anjou

Mary, Queen of Scots

Henry Stuart, Lord Darnley

James Hepburn, Earl of Bothwell

Anthony Babington and the Babington Plot

John Knox

Philip II of Spain

The Spanish Armada, 1588

Sir Francis Drake

Sir John Hawkins

William Camden

Archbishop Whitgift

Martin Marprelate Controversy

John Penry (Martin Marprelate)

Richard Bancroft, Archbishop of Canterbury

John Dee, Alchemist

Philip Henslowe

Edward Alleyn

The Blackfriars Theatre

The Fortune Theatre

The Rose Theatre

The Swan Theatre

Children's Companies

The Admiral's Men

The Lord Chamberlain's Men

Citizen Comedy

The Isle of Dogs, 1597

Common Law

Court of Common Pleas

Court of King's Bench

Court of Star Chamber

Council of the North

Fleet Prison

Assize

Attainder

First Fruits & Tenths

Livery and Maintenance

Oyer and terminer

Praemunire

The Stuarts

King James I of England

Anne of Denmark

Henry, Prince of Wales

The Gunpowder Plot, 1605

George Villiers, 1st Duke of Buckingham

Robert Carr, Earl of Somerset

Arabella Stuart, Lady Lennox

William Alabaster

Bishop Hall

Bishop Thomas Morton

Archbishop William Laud

John Selden

Lucy Harington, Countess of Bedford

Henry Lawes

King Charles I

Queen Henrietta Maria

Long Parliament

Rump Parliament

Kentish Petition, 1642

Thomas Wentworth, Earl of Strafford

John Digby, Earl of Bristol

George Digby, 2nd Earl of Bristol

Thomas Fairfax, 3rd Lord Fairfax

Robert Devereux, 3rd E. of Essex

Robert Sidney, 2. E. of Leicester

Algernon Percy, E. of Northumberland

Henry Montagu, Earl of Manchester

Edward Montagu, 2. Earl of Manchester

The Restoration

King Charles II

King James II

Test Acts

Greenwich Palace

Hatfield House

Richmond Palace

Windsor Palace

Woodstock Manor

The Cinque Ports

Mermaid Tavern

Malmsey Wine

Great Fire of London, 1666

Merchant Taylors' School

Westminster School

The Sanctuary at Westminster

"Sanctuary"

Images:

Chart of the English Succession from William I through Henry VII

Medieval English Drama

London c1480, MS Royal 16

London, 1510, the earliest view in print

Map of England from Saxton's Descriptio Angliae, 1579

London in late 16th century

Location Map of Elizabethan London

Plan of the Bankside, Southwark, in Shakespeare's time

Detail of Norden's Map of the Bankside, 1593

Bull and Bear Baiting Rings from the Agas Map (1569-1590, pub. 1631)

Sketch of the Swan Theatre, c. 1596

Westminster in the Seventeenth Century, by Hollar

Visscher's View of London, 1616

Larger Visscher's View in Sections

c. 1690. View of London Churches, after the Great Fire

The Yard of the Tabard Inn from Thornbury, Old and New London

|

|