BECUMA OF THE WHITE SKIN.

THERE are more worlds than one, and in many ways they

are unlike each other. But joy and sorrow, or, in other

words, good and evil, are not absent in their degree from

any of the worlds, for wherever there is life there is action,

and action is but the expression of one or other of these

qualities.

After this Earth there is the world of the Shí. Beyond

it again lies the Many-Coloured Land. Next comes the

Land of Wonder, and after that the Land of Promise

awaits us. You will cross clay to get into the Shí; you will

cross water to attain the Many-Coloured Land; fire must

be passed ere the Land of Wonder is attained, but we do

not know what will be crossed for the fourth world.

This adventure of Conn the Hundred Fighter and his

son Art was by the way of water, and therefore he was

more advanced in magic than Fionn was, all of whose

adventures were by the path of clay and into Faery only,

but Conn was the High King and so the arch-magician

of Ireland.

A council had been called in the Many-Coloured Land

to discuss the case of a lady named Becuma Cneisgel, that

is, Becuma of the White Skin, the daughter of Eogan Inver.

She had run away from her husband Labraid and had taken

refuge with Gadiar, one of the sons of Manannán mac Lir,

the god of the sea, and the ruler, therefore, of that sphere.

It seems, then, that there is marriage in two other

spheres. In the Shí matrimony is recorded as being

parallel in every respect with earth — marriage, and the

desire which urges to it seems to be as violent and inconstant

as it is with us; but in the Many-Coloured Land marriage

is but a contemplation of beauty, a brooding and meditation

wherein all grosser desire is unknown and children

are born to sinless parents.

In the Shí the crime of Becuma would have been

lightly considered, and would have received none or but

a nominal punishment, but in the second world a horrid

gravity attaches to such a lapse, and the retribution meted

is implacable and grim. It may be dissolution by fire, and

that can note a destruction too final for the mind to contemplate;

or it may be banishment from that sphere to a lower

and worse one.

This was the fate of Becuma of the White Skin.

One may wonder how, having attained to that sphere,

she could have carried with her so strong a memory of the

earth. It is certain that she was not a fit person to exist

in the Many-Coloured Land, and it is to be feared that she

was organised too grossly even for life in the Shí.

She was an earth-woman, and she was banished to the

earth.

Word was sent to the Shís of Ireland that this lady

should not be permitted to enter any of them; from which

it would seem that the ordinances of the Shí come from the

higher world, and, it might follow, that the conduct of

earth lies in the Shí.

In that way, the gates of her own world and the innumerable

doors of Faery being closed against her, Becuma was

forced to appear in the world of men.

It is pleasant, however, notwithstanding her terrible

crime and her woeful punishment, to think how courageous

she was. When she was told her sentence, nay, her doom,

she made no outcry, nor did she waste any time in sorrow.

She went home and put on her nicest clothes.

She wore a red satin smock, and, over this, a cloak of

green silk out of which long fringes of gold swung and

sparkled, and she had light sandals of white bronze on her

thin shapely feet. She had long soft hair that was yellow

as gold, and soft as the curling foam of the sea. Her eyes

were wide and clear as water and were grey as a dove's

breast. Her teeth were white as snow and of an evenness

to marvel at. Her lips were thin and beautifully curved:

red lips in truth, red as winter berries and tempting as the

fruits of summer. The people who superintended her

departure said mournfully that when she was gone there

would be no more beauty left in their world.

She stepped into a coracle, it was pushed on the enchanted

waters, and it went forward, world within world, until land

appeared, and her boat swung in low tide against a rock at

the foot of Ben Edair.1

So far for her.

Conn the Hundred Fighter, Ard-Rí of Ireland, was in the

lowest spirits that can be imagined, for his wife was dead.

He had been Ard-Rí for nine years, and during his

term the corn used to be reaped three times in each year,

and there was full and plenty of everything. There are

few kings who can boast of more kingly results than he

can, but there was sore trouble in store for him.

He had been married to Eithne, the daughter of

Brisland Binn, King of Norway, and, next to his subjects,

he loved his wife more than all that was lovable in the

world. But the term of man and woman, of king or queen,

is set in the stars, and there is no escaping Doom for any

one; so, when her time came, Eithne died.

Now there were three great burying-places in Ireland —

the Brugh of the Boyne in Ulster, over which Angus Og

is chief and god; the Shí mound of Cruachan Ahi, where

Ethal Anbual presides over the underworld of Connacht;

and Tailltin, in Royal Meath. It was in this last, the sacred

place of his own lordship, that Conn laid his wife to rest.

Her funeral games were played during nine days. Her

keen was sung by poets and harpers, and a cairn ten acres

wide was heaved over her clay. Then the keening ceased

and the games drew to an end; the princes of the Five

Provinces returned by horse or by chariot to their own

places; the concourse of mourners melted away, and there

was nothing left by the great cairn but the sun that dozed

upon it in the daytime, the heavy clouds that brooded on

it in the night, and the desolate, memoried king.

For the dead queen had been so lovely that Conn could

not forget her; she had been so kind at every moment that

he could not but miss her at every moment; but it was in

the Council Chamber and the Judgement Hall that he most

pondered her memory. For she had also been wise, and

lacking her guidance, all grave affairs seemed graver, shadowing

each day and going with him to the pillow at night.

The trouble of the king becomes the trouble of the

subject, for how shall we live if judgement is withheld, or

if faulty decisions are promulgated? Therefore, with the

sorrow of the king, all Ireland was in grief, and it was the

wish of every person that he should marry again.

Such an idea, however, did not occur to him, for he

could not conceive how any woman should fill the place his

queen had vacated. He grew more and more despondent,

and less and less fitted to cope with affairs of state, and one

day he instructed his son Art to take the rule during his

absence, and he set out for Ben Edair.

For a great wish had come upon him to walk beside the

sea; to listen to the roll and boom of long, grey breakers;

to gaze on an unfruitful, desolate wilderness of waters;

and to forget in those sights all that he could forget, and

if he could not forget then to remember all that he should

remember.

He was thus gazing and brooding when one day he

observed a coracle drawing to the shore. A young girl

stepped from it and walked to him among black boulders

and patches of yellow sand.

Being a king he had authority to ask questions. Conn

asked her, therefore, all the questions that he could think

of, for it is not every day that a lady drives from the sea,

and she wearing a golden-fringed cloak of green silk through

which a red satin smock peeped at the openings. She

replied to his questions, but she did not tell him all the

truth; for, indeed, she could not afford to.

She knew who he was, for she retained some of the

powers proper to the worlds she had left, and as he

looked on her soft yellow hair and on her thin red

lips, Conn recognised, as all men do, that one who is

lovely must also be good, and so he did not frame any

inquiry on that count; for everything is forgotten in

the presence of a pretty woman, and a magician can be

bewitched also.

She told Conn that the fame of his son Art had reached

even the Many-Coloured Land, and that she had fallen in

love with the boy. This did not seem unreasonable to one

who had himself ventured much in Faery, and who had

known so many of the people of that world leave their own

land for the love of a mortal.

"What is your name, my sweet lady?" said the king.

"I am called Delvcaem (Fair Shape) and I am the

daughter of Morgan," she replied.

"I have heard much of Morgan," said the king. "He

is a very great magician."

During this conversation Conn had been regarding her

with the minute freedom which is right only in a king. At

what precise instant he forgot his dead consort we do not

know, but it is certain that at this moment his mind was no

longer burdened with that dear and lovely memory. His

voice was melancholy when he spoke again.

"You love my son!"

"Who could avoid loving him?" she murmured.

"When a woman speaks to a man about the love

she feels for another man she is not liked. And," he

continued, "when she speaks to a man who has no wife

of his own about her love for another man then she is

disliked."

"I would not be disliked by you," Becuma murmured.

"Nevertheless," said he regally, "I will not come

between a woman and her choice."

"I did not know you lacked a wife," said Becuma, but

indeed she did.

"You know it now," the king replied sternly.

"What shall I do?" she inquired; "am I to wed you

or your son?"

"You must choose," Conn answered.

"If you allow me to choose it means that you do not

want me very badly," said she with a smile.

"Then I will not allow you to choose," cried the king,

"and it is with myself you shall marry."

He took her hand in his and kissed it.

"Lovely is this pale thin hand. Lovely is the slender

foot that I see in a small bronze shoe," said the king.

After a suitable time she continued:

"I should not like your son to be at Tara when I am

there, or for a year afterwards, for I do not wish to meet

him until I have forgotten him and have come to know

you well."

"I do not wish to banish my son," the king protested.

"It would not really be a banishment," she said. "A

prince's duty could be set him, and in such an absence he

would improve his knowledge both of Ireland and of men.

Further," she continued with downcast eyes, "when you

remember the reason that brought me here you will see

that his presence would be an embarrassment to us both, and

my presence would be unpleasant to him if he remembers

his mother."

"Nevertheless," said Conn stubbornly, "I do not wish

to banish my son; it is awkward and unnecessary."

"For a year only," she pleaded.

"It is yet," he continued thoughtfully, "a reasonable

reason that you give and I will do what you ask, but by

my hand and word I don't like doing it."

They set out then briskly and joyfully on the homeward

journey, and in due time they reached Tara of the

Kings.

It is part of the education of a prince to be a good chess

player, and to continually exercise his mind in view of the

judgements that he will be called upon to give and the

knotty, tortuous, and perplexing matters which will obscure

the issues which he must judge. Art, the son of Conn,

was sitting at chess2 with Cromdes, his father's magician.

Be very careful about the move you are going to

make," said Cromdes.

"Can I be careful?" Art inquired. "Is the move that

you are thinking of in my power?"

"It is not," the other admitted.

"Then I need not be more careful than usual," Art

replied, and he made his move.

"It is a move of banishment," said Cromdes.

"As I will not banish myself, I suppose my father will

do it, but I do not know why he should."

"Your father will not banish you."

"Who then?"

"Your mother."

"My mother is dead."

"You have a new one," said the magician.

"Here is news," said Art. "I think I shall not love

my new mother."

"You will yet love her better than she loves you," said

Cromdes, meaning thereby that they would hate each

other.

While they spoke the king and Becuma entered the

palace.

"I had better go to greet my father," said the young

man.

"You had better wait until he sends for you," his

companion advised, and they returned to their game.

In due time a messenger came from the king directing

Art to leave Tara instantly, and to leave Ireland for one

full year.

He left Tara that night, and for the space of a year he

was not seen again in Ireland. But during that period

things did not go well with the king nor with Ireland.

Every year before that time three crops of corn used to be

lifted off the land, but during Art's absence there was no

corn in Ireland and there was no milk. The whole land

went hungry.

Lean people were in every house, lean cattle in every

field; the bushes did not swing out their timely berries or

seasonable nuts; the bees went abroad as busily as ever,

but each night they returned languidly, with empty pouches,

and there was no honey in their hives when the honey

season came. People began to look at each other questioningly,

meaningly, and dark remarks passed between them,

for they knew that a bad harvest means, somehow, a bad

king, and, although this belief can be combated, it is too firmly

rooted in wisdom to be dismissed.

The poets and magicians met to consider why this

disaster should have befallen the country, and by their arts

they discovered the truth about the king's wife, and that

she was Becuma of the White Skin, and they discovered

also the cause of her banishment from the Many-Coloured

Land that is beyond the sea, which is beyond even the

grave.

They told the truth to the king, but he could not bear

to be parted from that slender-handed, gold-haired, thin-lipped,

blithe enchantress, and he required them to discover

some means whereby he might retain his wife and his

crown. There was a way and the magicians told him of it.

"If the son of a sinless couple can be found and if his

blood be mixed with the soil of Tara the blight and ruin

will depart from Ireland," said the magicians.

"If there is such a boy I will find him," cried the

Hundred Fighter.

At the end of a year Art returned to Tara. His father

delivered to him the sceptre of Ireland, and he set out on a

journey to find the son of a sinless couple such as he had

been told of.

The High King did not know where exactly he should

look for such a saviour, but he was well educated and knew

how to look for whatever was lacking. This knowledge

will be useful to those upon whom a similar duty should

ever devolve.

He went to Ben Edair. He stepped into a coracle and

pushed out to the deep, and he permitted the coracle to

go as the winds and the waves directed it.

In such a way he voyaged among the small islands of

the sea until he lost all knowledge of his course and was

adrift far out in ocean. He was under the guidance of the

stars and the great luminaries.

He saw black seals that stared and barked and dived

dancingly, with the round turn of a bow and the forward

onset of an arrow. Great whales came heaving from the

green-hued void, blowing a wave of the sea high into the

air from their noses and smacking their wide flat tails

thunderously on the water. Porpoises went snorting past

in bands and clans. Small fish came sliding and flickering,

and all the outlandish creatures of the deep rose by his

bobbing craft and swirled and sped away.

Wild storms howled by him so that the boat climbed

painfully to the sky on a mile-high wave, balanced for a

tense moment on its level top, and sped down the glassy

side as a stone goes furiously from a sling.

Or, again, caught in the chop of a broken sea, it

stayed shuddering and backing, while above his head there

was only a low sad sky, and around him the lap and wash

of grey waves that were never the same and were never

different.

After long staring on the hungry nothingness of air and

water he would stare on the skin-stretched fabric of his boat

as on a strangeness, or he would examine his hands and the

texture of his skin and the stiff black hairs that grew behind

his knuckles and sprouted around his ring, and he found

in these things newness and wonder.

Then, when days of storm had passed, the low grey

clouds shivered and cracked in a thousand places, each grim

islet went scudding to the horizon as though terrified by

some great breadth, and when they had passed he stared

into vast after vast of blue infinity, in the depths of which

his eyes stayed and could not pierce, and wherefrom they

could scarcely be withdrawn. A sun beamed thence that

filled the air with sparkle and the sea with a thousand lights,

and looking on these he was reminded of his home at Tara:

of the columns of white and yellow bronze that blazed

out sunnily on the sun, and the red and white and yellow

painted roofs that beamed at and astonished the eye.

Sailing thus, lost in a succession of days and nights, of

winds and calms, he came at last to an island.

His back was turned to it, and long before he saw it he

smelled it and wondered; for he had been sitting as in a

daze, musing on a change that had seemed to come in his

changeless world; and for a long time he could not tell

what that was which made a difference on the salt-whipped

wind or why he should be excited. For suddenly he had

become excited and his heart leaped in violent expectation.

"It is an October smell," he said.

"It is apples that I smell."

He turned then and saw the island, fragrant with apple

trees, sweet with wells of wine; and, hearkening towards

the shore, his ears, dulled yet with the unending rhythms

of the sea, distinguished and were filled with song; for

the isle was, as it were, a nest of birds, and they sang

joyously, sweetly, triumphantly.

He landed on that lovely island, and went forward

under the darting birds, under the apple boughs, skirting

fragrant lakes about which were woods of the sacred hazel

and into which the nuts of knowledge fell and swam; and

he blessed the gods of his people because of the ground

that did not shiver and because of the deeply rooted trees

that could not gad or budge.

Having gone some distance by these pleasant ways he saw

a shapely house dozing in the sunlight.

It was thatched with the wings of birds, blue wings

and yellow and white wings, and in the centre of the house

there was a door of crystal set in posts of bronze.

The queen of this island lived there, Rigru (Large-eyed),

the daughter of Lodan, and wife of Daire Degamra.

She was seated on a crystal throne with her son Segda by

her side, and they welcomed the High King courteously.

There were no servants in this palace; nor was there

need for them. The High King found that his hands had

washed themselves, and when later on he noticed that food

had been placed before him he noticed also that it had come

without the assistance of servile hands. A cloak was laid

gently about his shoulders, and he was glad of it, for his

own was soiled by exposure to sun and wind and water,

and was not worthy of a lady's eye.

Then he was invited to eat.

He noticed, however, that food had been set for no one

but himself, and this did not please him, for to eat alone

was contrary to the hospitable usage of a king, and was

contrary also to his contract with the gods.

"Good my hosts," he remonstrated, "it is geasa (taboo)

for me to eat alone."

"But we never eat together," the queen replied.

"I cannot violate my geasa," said the High King.

"I will eat with you," said Segda (Sweet Speech)," and

thus, while you are our guest you will not do violence to

your vows."

"Indeed," said Conn, "that will be a great satisfaction,

for I have already all the trouble that I can cope with and

have no wish to add to it by offending the gods."

"What is your trouble?" the gentle queen asked.

"During a year," Conn replied, "there has been

neither corn nor milk in Ireland. The land is parched,

the trees are withered, the birds do not sing in Ireland, and

the bees do not make honey."

"You are certainly in trouble," the queen assented.

"But," she continued, "for what purpose have you

come to our island?"

"I have come to ask for the loan of your son."

"A loan of my son!"

"I have been informed," Conn explained, ** that if the

son of a sinless couple is brought to Tara and is bathed in

the waters of Ireland the land will be delivered from those

ills."

The king of this island, Daire, had not hitherto spoken,

but he now did so with astonishment and emphasis.

"We would not lend our son to any one, not even to

gain the kingship of the world," said he.

But Segda, observing that the guest's countenance was

discomposed, broke in:

"It is not kind to refuse a thing that the Ard-Rí of

Ireland asks for, and I will go with him."

"Do not go, my pulse," his father advised.

"Do not go, my one treasure," his mother pleaded.

"I must go indeed," the boy replied, "for it is to do

good I am required, and no person may shirk such a requirement."

"Go then," said his father, "but I will place you under

the protection of the High King and of the Four Provincial

Kings of Ireland, and under the protection of Art, the son

of Conn, and of Fionn, the son of Uail, and under the

protection of the magicians and poets and the men of art

in Ireland." And he thereupon bound these protections

and safeguards on the Ard-Rí with an oath.

"I will answer for these protections," said Conn.

He departed then from the island with Segda and in

three days they reached Ireland, and in due time they

arrived at Tara.

On reaching the palace Conn called his magicians and poets

to a council and informed them that he had found the boy

they sought — the son of a virgin. These learned people

consulted together, and they stated that the young man

must be killed, and that his blood should be mixed with

the earth of Tara and sprinkled under the withered trees.

When Segda heard this he was astonished and defiant;

then, seeing that he was alone and without prospect of

succour, he grew downcast and was in great fear for his

life. But remembering the safeguards under which he had

been placed, he enumerated these to the assembly, and

called on the High King to grant him the protections that

were his due.

Conn was greatly perturbed, but, as in duty bound,

he placed the boy under the various protections that were

in his oath, and, with the courage of one who has no more

to gain or lose, he placed Segda, furthermore, under the

protection of all the men of Ireland.

But the men of Ireland refused to accept that bond,

saying that although the Ard-Rí was acting justly towards

the boy he was not acting justly towards Ireland.

"We do not wish to slay this prince for our pleasure,"

they argued, " but for the safety of Ireland he must be

killed."

Angry parties were formed. Art, and Fionn the son of

Uail, and the princes of the land were outraged at the idea

that one who had been placed under their protection should

be hurt by any hand. But the men of Ireland and the

magicians stated that the king had gone to Faery for a

special purpose, and that his acts outside or contrary to

that purpose were illegal, and committed no person to

obedience.

There were debates in the Council Hall, in the market-

place, in the streets of Tara, some holding that national

honour dissolved and absolved all personal honour, and

others protesting that no man had aught but his personal

honour, and that above it not the gods, not even Ireland,

could be placed — for it is to be known that Ireland is a god.

Such a debate was in course, and Segda, to whom both

sides addressed gentle and courteous arguments, grew more

and more disconsolate.

"You shall die for Ireland, dear heart," said one of them,

and he gave Segda three kisses on each cheek.

"Indeed," said Segda, returning those kisses, "indeed

I had not bargained to die for Ireland, but only to bathe in

her waters and to remove her pestilence."

"But, dear child and prince," said another, kissing him

likewise, "if any one of us could save Ireland by dying for

her how cheerfully we would die."

And Segda, returning his three kisses, agreed that the

death was noble, but that it was not in his undertaking.

Then, observing the stricken countenances about him,

and the faces of men and women hewn thin by hunger, his

resolution melted away, and he said:

"I think I must die for you," and then he said:

"I will die for you."

And when he had said that, all the people present

touched his cheek with their lips, and the love and peace of

Ireland entered into his soul, so that he was tranquil and

proud and happy.

The executioner drew his wide, thin blade and all

those present covered their eyes with their cloaks, when a

wailing voice called on the executioner to delay yet a

moment. The High King uncovered his eyes and saw

that a woman had approached driving a cow before her.

"Why are you killing the boy?" she demanded.

The reason for this slaying was explained to her.

Are you sure," she asked, "that the poets and

magicians really know everything?"

"Do they not?" the king inquired.

"Do they?" she insisted.

And then turning to the magicians:

"Let one magician of the magicians tell me what is

hidden in the bags that are lying across the back of my

cow."

But no magician could tell it, nor did they try to.

"Questions are not answered thus," they said. "There

are formulae, and the calling up of spirits, and lengthy

complicated preparations in our art."

I am not badly learned in these arts," said the woman,

"and I say that if you slay this cow the effect will be the

same as if you had killed the boy."

"We would prefer to kill a cow or a thousand cows

rather than harm this young prince," said Conn, "but if we

spare the boy will these evils return?"

"They will not be banished until you have banished

their cause."

"And what is their cause?"

"Becuma is the cause, and she must be banished."

"If you must tell me what to do," said Conn, "tell

me at least to do something that I can do."

"I will tell you certainly. You can keep Becuma

and your ills as long as you want to. It does not matter

to me. Come, my son," she said to Segda, for it was

Segda's mother who had come to save him; and then that

sinless queen and her son went back to their home of

enchantment, leaving the king and Fionn and the magicians

and nobles of Ireland astonished and ashamed.

There are good and evil people in this and in every other

world, and the person who goes hence will go to the good

or the evil that is native to him, while those who return

come as surely to their due. The trouble which had fallen

on Becuma did not leave her repentant, and the sweet

lady began to do wrong as instantly and innocently as a

flower begins to grow. It was she who was responsible for

the ills which had come on Ireland, and we may wonder

why she brought these plagues and droughts to what was

now her own country.

Under all wrong-doing lies personal vanity or the

feeling that we are endowed and privileged beyond our

fellows. It is probable that, however courageously she had

accepted fate, Becuma had been sharply stricken in her

pride; in the sense of personal strength, aloofness, and

identity, in which the mind likens itself to god and will

resist every domination but its own. She had been punished,

that is, she had submitted to control, and her sense of

freedom, of privilege, of very being, was outraged. The

mind flinches even from the control of natural law, and how

much more from the despotism of its own separated likenesses,

for if another can control me that other has usurped

me, has become me, and how terribly I seem diminished

by the seeming addition!

This sense of separateness is vanity, and is the bed of all

wrong-doing. For we are not freedom, we are control, and

we must submit to our own function ere we can exercise it.

Even unconsciously we accept the rights of others to all that

we have, and if we will not share our good with them, it is

because we cannot, having none; but we will yet give what

we have, although that be evil. To insist on other people

sharing in our personal torment is the first step towards

insisting that they shall share in our joy, as we shall insist

when we get it.

Becuma considered that if she must suffer all else

she met should suffer also. She raged, therefore, against

Ireland, and in particular she raged against young Art,

her husband's son, and she left undone nothing that could

afflict Ireland or the prince. She may have felt that she

could not make them suffer, and that is a maddening

thought to any woman. Or perhaps she had really

desired the son instead of the father, and her thwarted

desire had perpetuated itself as hate. But it is true that

Art regarded his mother's successor with intense dislike,

and it is true that she actively returned it.

One day Becuma came on the lawn before the palace,

and seeing that Art was at chess with Cromdes she walked

to the table on which the match was being played and for

some time regarded the game. But the young prince

did not take any notice of her while she stood by the

board, for he knew that this girl was the enemy of Ireland,

and he could not bring himself even to look at her.

Becuma, looking down on his beautiful head, smiled

as much in rage as in disdain.

"O son of a king," said she, "I demand a game with

you for stakes."

Art then raised his head and stood up courteously,

but he did not look at her.

"Whatever the queen demands I will do," said he.

"Am I not your mother also," she replied mockingly,

as she took the seat which the chief magician leaped from.

The game was set then, and her play was so skilful

that Art was hard put to counter her moves. But at a

point of the game Becuma grew thoughtful, and, as by a

lapse of memory, she made a move which gave the victory

to her opponent. But she had intended that. She sat

then, biting on her lip with her white small teeth and

staring angrily at Art.

What do you demand from me?" she asked.

"I bind you to eat no food in Ireland until you find the

wand of Curoi, son of Darè."

Becuma then put a cloak about her and she went from

Tara northward and eastward until she came to the dewy,

sparkling Brugh of Angus mac an Og in Ulster, but she

was not admitted there. She went thence to the Shí

ruled over by Eogabal, and although this lord would not

admit her, his daughter Ainè, who was her foster-sister,

let her into Faery. She made inquiries and was informed

where the dun of Curoi mac Darè was, and when she had

received this intelligence she set out for Sliev Mis. By

what arts she coaxed Curoi to give up his wand it matters

not, enough that she was able to return in triumph to

Tara. When she handed the wand to Art, she said:

"I claim my game of revenge."

"It is due to you," said Art, and they sat on the lawn

before the palace and played.

A hard game that was, and at times each of the combatants

sat for an hour staring on the board before the next

move was made, and at times they looked from the board

and for hours stared on the sky seeking as though in heaven

for advice. But Becuma's foster-sister, Ainè, came from

the Shí, and, unseen by any, she interfered with Art's

play, so that, suddenly, when he looked again on the board,

his face went pale, for he saw that the game was lost.

"I didn't move that piece," said he sternly.

"Nor did I," Becuma replied, and she called on the

onlookers to confirm that statement.

She was smiling to herself secretly, for she had seen

what the mortal eyes around could not see.

"I think the game is mine," she insisted softly.

"I think that your friends in Faery have cheated,"

he replied, "but the game is yours if you are content to

win it that way."

"I bind you," said Becuma, "to eat no food in Ireland

until you have found Delvcaem, the daughter of Morgan."

"Where do I look for her," said Art in despair.

"She is in one of the islands of the sea," Becuma

replied, "that is all I will tell you," and she looked at him

maliciously, joyously, contentedly, for she thought he would

never return from that journey, and that Morgan would

see to it.

Art, as his father had done before him, set out for the

Many- Coloured Land, but it was from Inver Colpa he embarked

and not from Ben Edair.

At a certain time he passed from the rough green ridges

of the sea to enchanted waters, and he roamed from island

to island asking all people how he might come to Delvcaem,

the daughter of Morgan. But he got no news from any one,

until he reached an island that was fragrant with wild apples,

gay with flowers, and joyous with the song of birds and the

deep mellow drumming of the bees. In this island he

was met by a lady, Credè, the Truly Beautiful, and when

they had exchanged kisses, he told her who he was and

on what errand he was bent.

"We have been expecting you," said Crede, "but alas,

poor soul, it is a hard, and a long, bad way that you must

go; for there is sea and land, danger and difficulty between

you and the daughter of Morgan."

"Yet I must go there," he answered.

"There is a wild dark ocean to be crossed. There is

a dense wood where every thorn on every tree is sharp as a

spear-point and is curved and clutching. There is a deep

gulf to be gone through," she said, "a place of silence and

terror, full of dumb, venomous monsters. There is an

immense oak forest — dark, dense, thorny, a place to be

strayed in, a place to be utterly bewildered and lost in.

There is a vast dark wilderness, and therein is a dark house,

lonely and full of echoes, and in it there are seven gloomy

hags, who are warned already of your coming and are

waiting to plunge you in a bath of molten lead."

"It is not a choice journey," said Art, "but I have no

choice and must go."

"Should you pass those hags," she continued, "and

no one has yet passed them, you must meet Ailill of the

Black Teeth, the son of Mongan Tender Blossom, and who

could pass that gigantic and terrible fighter."

"It is not easy to find the daughter of Morgan," said

Art in a melancholy voice.

"It is not easy," Credè replied eagerly, "and if you

will take my advice—"

"Advise me," he broke in, "for in truth there is no

man standing in such need of counsel as I do."

"I would advise you," said Credè in a low voice, "to

seek no more for the sweet daughter of Morgan, but to

stay in this place where all that is lovely is at your service."

"But, but—" cried Art in astonishment.

"Am I not as sweet as the daughter of Morgan?" she

demanded, and she stood before him queenly and pleadingly,

and her eyes took his with imperious tenderness.

"By my hand," he answered, "you are sweeter and

lovelier than any being under the sun, but—"

"And with me," she said, "you will forget Ireland."

"I am under bonds," cried Art, "I have passed my

word, and I would not forget Ireland or cut myself from it

for all the kingdoms of the Many-Coloured Land."

Credè urged no more at that time, but as they were

parting she whispered, "There are two girls, sisters of

my own, in Morgan's palace. They will come to you with

a cup in either hand; one cup will be filled with wine and

one with poison. Drink from the right-hand cup, O my

dear."

Art stepped into his coracle, and then, wringing her

hands, she made yet an attempt to dissuade him from that

drear journey.

"Do not leave me," she urged. "Do not affront

these dangers. Around the palace of Morgan there is a

palisade of copper spikes, and on the top of each spike the

head of a man grins and shrivels. There is one spike

only which bears no head, and it is for your head that spike

is waiting. Do not go there, my love."

"I must go indeed," said Art earnestly.

"There is yet a danger," she called. "Beware of

Delvcaem's mother. Dog Head, daughter of the King of

the Dog Heads. Beware of her."

"Indeed," said Art to himself, "there is so much to

beware of that I will beware of nothing. I will go about

my business," he said to the waves, "and I will let those

beings and monsters and the people of the Dog Heads go

about their business."

He went forward in his light bark, and at some moment

found that he had parted from those seas and was adrift on

vaster and more turbulent billows. From those dark-green

surges there gaped at him monstrous and cavernous jaws;

and round, wicked, red-rimmed, bulging eyes stared fixedly

at the boat. A ridge of inky water rushed foaming mountainously

on his board, and behind that ridge came a vast

warty head that gurgled and groaned. But at these vile

creatures he thrust with his lengthy spear or stabbed at

closer reach with a dagger.

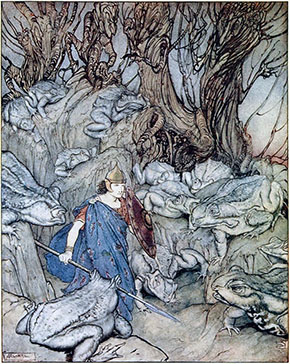

He was not spared one of the terrors which had been

foretold. Thus, in the dark thick oak forest he slew the

seven hags and buried them in the molten lead which they

had heated for him. He climbed an icy mountain, the cold

breath of which seemed to slip into his body and chip off

inside of his bones, and there, until he mastered the sort of

climbing on ice, for each step that he took upwards he

slipped back ten steps. Almost his heart gave way before

he learned to climb that venomous hill.

In a forked glen

into which he slipped at nightfall he was surrounded by

giant toads, who spat poison, and were icy as the land they

lived in, and were cold and foul and savage. At Sliav

Saev he encountered the long-maned lions who lie in wait

for the beasts of the world, growling woefully as they squat

above their prey and crunch those terrified bones. He

came on Ailill of the Black Teeth sitting on the bridge

that spanned a torrent, and the grim giant was grinding

his teeth on a pillar stone. Art drew nigh unobserved and

brought him low.

It was not for nothing that these difficulties and dangers

were in his path. These things and creatures were the

invention of Dog Head, the wife of Morgan, for it had

become known to her that she would die on the day

her daughter was wooed. Therefore none of the dangers

encountered by Art were real, but were magical chimeras

conjured against him by the great witch.

Affronting all, conquering all, he came in time to

Morgan's dun, a place so lovely that after the miseries

through which he had struggled he almost wept to see

beauty again.

Delvcaem knew that he was coming. She was waiting

for him, yearning for him. To her mind Art was not only

love, he was freedom, for the poor girl was a captive in

her father's home. A great pillar an hundred feet high

had been built on the roof of Morgan's palace, and on the

top of this pillar a tiny room had been constructed, and in

this room Delvcaem was a prisoner.

She was lovelier in shape than any other princess of

the Many-Coloured Land. She was wiser than all the

other women of that land, and she was skilful in music,

embroidery, and chastity, and in all else that pertained to

the knowledge of a queen.

Although Delvcaem's mother wished nothing but ill to

Art, she yet treated him with the courtesy proper in a

queen on the one hand and fitting towards the son of

the King of Ireland on the other. Therefore, when Art

entered the palace he was met and kissed, and he was bathed

and clothed and fed. Two young girls came to him then,

having a cup in each of their hands, and presented him with

the kingly drink, but, remembering the warning which

Credè had given him, he drank only from the right-hand

cup and escaped the poison.

Next he was visited by Delvcaem's mother. Dog Head,

daughter of the King of the Dog Heads, and Morgan's

queen. She was dressed in full armour, and she challenged

Art to fight with her.

It was a woeful combat, for there was no craft or

sagacity unknown to her, and Art would infallibly have

perished by her hand but that her days were numbered,

her star was out, and her time had come. It was her head

that rolled on the ground when the combat was over, and

it was her head that grinned and shrivelled on the vacant

spike which she had reserved for Art's.

Then Art liberated Delvcaem from her prison at the

top of the pillar and they were affianced together. But the

ceremony had scarcely been completed when the tread of

a single man caused the palace to quake and seemed to jar

the world.

It was Morgan returning to the palace.

The gloomy king challenged him to combat also, and

in his honour Art put on the battle harness which he had

brought from Ireland. He wore a breastplate and helmet

of gold, a mantle of blue satin swung from his shoulders,

his left hand was thrust into the grips of a purple shield,

deeply bossed with silver, and in the other hand he held

the wide-grooved, blue-hiked sword which had rung

so often into fights and combats, and joyous feats and

exercises.

Up to this time the trials through which he had passed

had seemed so great that they could not easily be added to.

But if all those trials had been gathered into one vast

calamity they would not equal one half of the rage and

catastrophe of his war with Morgan.

For what he could not effect by arms Morgan would

endeavour by guile, so that while Art drove at him or

parried a crafty blow, the shape of Morgan changed before

his eyes, and the monstrous king was having at him in

another form, and from a new direction.

It was well for the son of the Ard-Rí that he had been

beloved by the poets and magicians of his land, and that

they had taught him all that was known of shape-changing

and words of power.

He had need of all these.

At times, for the weapon must change with the enemy,

they fought with their foreheads as two giant stags, and the

crash of their monstrous onslaught rolled and lingered on

the air long after their skulls had parted. Then as two

lions, long-clawed, deep-mouthed, snarling, with rigid

mane, with red-eyed glare, with flashing, sharp-white

fangs, they prowled lithely about each other seeking for

an opening. And then as two green-ridged, white-topped,

broad-swung, overwhelming, vehement billows of the deep,

they met and crashed and sank into and rolled away from

each other; and the noise of these two waves was as the

roar of all ocean when the howl of the tempest is drowned

in the league-long fury of the surge.

But when the wife's time has come the husband is

doomed. He is required elsewhere by his beloved, and

Morgan went to rejoin his queen in the world that comes

after the Many-Coloured Land, and his victor shore that

knowledgeable head away from its giant shoulders.

He did not tarry in the Many-Coloured Land, for he

had nothing further to seek there. He gathered the things

which pleased him best from among the treasures of its

grisly king, and with Delvcaem by his side they stepped

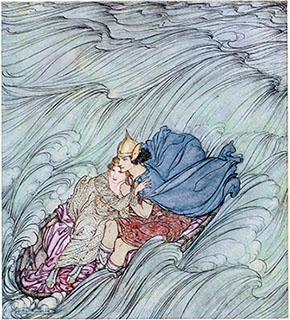

into the coracle.

Then, setting their minds on Ireland, they went there

as it were in a flash.

The waves of all the worlds seemed to whirl past them in

one huge green cataract. The sound of all these oceans

boomed in their ears for one eternal instant. Nothing was

for that moment but a vast roar and pour of waters. Thence

they swung into a silence equally vast, and so sudden that

it was as thunderous in the comparison as was the elemental

rage they quitted. For a time they sat panting, staring at

each other, holding each other, lest not only their lives but

their very souls should be swirled away in the gusty passage

of world within world; and then, looking abroad, they saw

the small bright waves creaming by the rocks of Ben Edair,

and they blessed the power that had guided and protected

them, and they blessed the comely land of Ir.

On reaching Tara, Delvcaem, who was more powerful

in art and magic than Becuma, ordered the latter to go

away, and she did so.

She left the king's side. She came from the midst of

the counsellors and magicians. She did not bid farewell

to any one. She did not say good-bye to the king as she

set out for Ben Edair.

Where she could go to no man knew, for she had been

banished from the Many-Coloured Land and could not return

there. She was forbidden entry to the Shí by Angus Og,

and she could not remain in Ireland. She went to Sasana3

and she became a queen in that country, and it was she who

fostered the rage against the Holy Land which has not

ceased to this day.

[AJ Notes:

The original of this tale is in the Book of Fermoy, compiled in the 14th century, now in the Royal Irish Academy. For a transcription and translation, see

"The Adventures of Art Son of Conn", by R. I. Best, in Ériu, Vol. III, Kuno Meyer and John Strachan, eds., Dublin: David Nutt, 1907, 149-173. -> online.

1. Ben of Howth, near Dublin.

2. The original story has fidchell, an ancient celtic boardgame.

3. Old Irish name for England.]

Text Source:

Stephens, James, ed. Irish Fairy Tales.

London: The Macmillan Co., Ltd., 1920. 219-255.

|