|

|

|

|

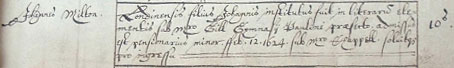

John Milton was born on December 9, 1608, in London, as the second child of John and Sara (neé Jeffrey). The family lived on Bread Street in Cheapside, near St. Paul's Cathedral. John Milton Sr. worked as a scrivener, a legal secretary whose duties included preparation and notarization of documents , as well as real estate transactions and moneylending. Milton's father was also a composer of church music, and Milton himself experienced a lifelong delight in music. The family's financial prosperity afforded Milton to be taught classical languages, first by private tutors at home, followed by entrance to St. Paul's School at age twelve, in 1620.

John Milton was born on December 9, 1608, in London, as the second child of John and Sara (neé Jeffrey). The family lived on Bread Street in Cheapside, near St. Paul's Cathedral. John Milton Sr. worked as a scrivener, a legal secretary whose duties included preparation and notarization of documents , as well as real estate transactions and moneylending. Milton's father was also a composer of church music, and Milton himself experienced a lifelong delight in music. The family's financial prosperity afforded Milton to be taught classical languages, first by private tutors at home, followed by entrance to St. Paul's School at age twelve, in 1620.

In 1625, Milton was admitted to Christ's College, Cambridge. While Milton was a hardworking student, he was also argumentative to the extent that only a year later, in 1626, he got suspended after a dispute with his tutor, William Chappell.

During his temporary return to London, Milton attended plays, and perhaps began his first forays into poetry. At his return to Cambridge, Milton was assigned a new tutor, Nathaniel Tovey. Life at Cambridge was still not easy on Milton; he felt he was disliked by many of his fellow students and he was dissatisfied with the curriculum. It was at Cambridge that he composed "On the Morning of Christ's Nativity" on December 25, 1629.

In 1632, Milton took his M.A. cum laude at Cambridge, after which he retired to the family homes in London and Horton, Buckinghamshire, for years of private study and literary composition.1 His poem, "On Shakespeare", was published in the same year in the Second Folio. From this period hail also his "L'Allegro" and "Il Penseroso." Milton's Comus, a masque, was performed at Ludlow Castle in 1634, to be first published anonymously in 1637, music by the famed court composer Henry Lawes. In April 1637, Milton was nearing the end of his studies when his mother died and was buried at Horton. Only a few months later, in August, Milton's friend Edward King died as well, by drowning. In November, upon his memory, Milton composed the beautiful elegy, Lycidas. It was published in a memorial volume at Cambridge in 1638. In 1632, Milton took his M.A. cum laude at Cambridge, after which he retired to the family homes in London and Horton, Buckinghamshire, for years of private study and literary composition.1 His poem, "On Shakespeare", was published in the same year in the Second Folio. From this period hail also his "L'Allegro" and "Il Penseroso." Milton's Comus, a masque, was performed at Ludlow Castle in 1634, to be first published anonymously in 1637, music by the famed court composer Henry Lawes. In April 1637, Milton was nearing the end of his studies when his mother died and was buried at Horton. Only a few months later, in August, Milton's friend Edward King died as well, by drowning. In November, upon his memory, Milton composed the beautiful elegy, Lycidas. It was published in a memorial volume at Cambridge in 1638.

As customary for young gentlemen of means, Milton set out for a tour of Europe in the spring of 1638. He met famed scholar Hugo Grotius in Paris, where he stayed briefly before continuing on to Italy. Milton arrived in Florence in the autumn, where he probably met with Galileo, who was then under house arrest by order of the Inquisition. In Rome, he was a guest of Cardinal Barberini, the Pope's nephew, and visited the Vatican Library. In Naples, Milton met Giovanni Batista, biographer of Torquato Tasso. Milton wrote Mansus in his honor. Upon reaching Geneva to visit with Calvinist theologian Giovanni Diodati, Milton found out about the death of his childhood friend, Charles Diodati in London. Milton's tour of Europe was cut short with rumors of impending civil war in England, and he returned home in July 1639. Shortly after, Milton composed Epitaphium Damonis, a Latin poem to the memory of his dearest friend.

Milton settled down in London, where he began schooling his two nephews, later also taking in children of the better families. The Civil War was brewing — King Charles I invaded Scotland in 1639, and the Long Parliament was convened in 1640. Milton began writing pamphlets on political and religious matters; Of Reformation, Animadversions, and Of Prelatical Episcopacy were published in 1641, The Reason for Church Government in February, 1642.

In the spring of 1642, Milton married Mary Powell, 17 years old to his 34, but the relationship was an unhappy one, and Mary left him to visit the family home briefly thereafter, and did not return. Matters were not improved when the Powells declared for the King in the Civil War which broke out in August. This prompted Milton to write his so-called 'Divorce Tracts' speaking for divorce on the grounds of incompatibility. In 1643, Milton published the Doctrine and Discipline of Divorce, which had its second, longer edition in early 1644. In 1644, Milton also published The Judgement of Martin Bucer Concerning Divorce. The 'Divorce Tracts' caused an uproar both in parliament and amidst the clergy, as well as with the general populace, which earned him the nickname "Milton the Divorcer."2 It is in reference to the attempted censorship of the same by the Stationers' Company, that Milton published his eloquent Areopagitica, an oration advocating freedom of the press, in late 1644.3 Milton had also had time to write a treatise Of Education, which prescribed a rigorous course of study for English youth. In 1645, Milton published Tetrachordon and Colasterion, and registered Poems of Mr. John Milton, Both English and Latin.

Milton had made plans to remarry, when Mary Powell returned. The two seem to have reconciled, since their daughter Anne was born in 1646. The whole Powell clan moved in with the Miltons, because Royalists had been ousted from Oxford. The situation was not savory. The year 1647 saw the death of both Milton's father and his father-in-law. The Powells eventually moved out and the Miltons moved to the neighborhood of High Holborn, where their daughter Mary was born in 1648.

It is probable that Milton witnessed the public execution of Charles I on January 30, 1649.4 Tenure of Kings and Magistrates was published two weeks later. In March, the Cromwellian government appointed Milton Secretary for Foreign Tongues and ordered him to write an answer to Charles I's purported Eikon Basilike ("Royal Image"). After publishing Observations on the Articles of Peace, Milton published Eikonoklastes ("Image Breaker") in October, 1649. In 1650, the Council of State ordered Milton to write a response to Salmasius' Defensio Regia — the Continental outcry against the English action ("Defense of Kingship"). Defensio pro populo Anglicano was published in February, 1651. Milton's first son, John, was born in March and the Miltons moved to Westminster.

The year 1652 was one of many personal losses for Milton. In February, Milton lost his sight. This prompted him to write the sonnet "When I Consider How My Light is Spent." In May, 1652, Mary gave birth to a daughter, Deborah, and died a few days later. In June, one year-old John died.

In 1654, Milton published Defensio Secunda, the response he had been ordered to write for Pierre du Moulin's Regii sanguinis clamor ("Clamor of the King's Blood"). Andrew Marvell had become his assistant, and he had aides to take dictation, to facilitate the carrying out of his duties as Secretary. In 1655, Defensio Pro Se ("Defense of Himself") was published. In 1656, Milton married Katherine Woodcock, but the happiness was short-lived. Milton's daughter Katherine was born in late 1657, but by early 1658, both mother and daughter had passed away. It is to the memory of Katherine Woodcock that Milton wrote the sonnet "Methought I saw my late espousèd saint."

Lord Protector Oliver Cromwell died in October, 1658, and the days of the Commonwealth were coming to a close. In early 1659, Milton published A Treatise of Civil Power and Ready and Easy Way To Establish a Free Commonwealth. For his propaganda writings, Milton had to go into hiding, for fear of retribution from the followers of King Charles II. In June, 1659, both Defensio pro populo Anglicano and Eikonoklastes were publicly burned. In early autumn, Milton was arrested and thrown in prison, to be released by order of Parliament before Christmas. King Charles II was restored to the throne on May 30, 1660.

In 1663, Milton remarried again, to Elizabeth Minshull, a match his daughters opposed. He spent his time tutoring students and finishing his life's work, the epic, Paradise Lost. Among the greatest works ever to be written in English, the feat is all the more remarkable for Milton's blindness — he would compose verse upon verse at night in his head and then dictate them from memory to his aides in the morning. Paradise Lost finally saw publication in 1667, in ten books. It was reissued in 1668 with a new title-page and additional materials. The book was met with instant success and amazement; even Dryden is reported to have said, "This man cuts us all out, and the ancients too."5

History of Britain was published in 1670; Paradise Regain'd and Samson Agonistes were published together in 1671. Of True Religion and Poems, &c. upon Several Occasions were published in 1673. In summer 1674, the second edition of Paradise Lost was published, in twelve books. Milton died peacefully of gout in November, 1674, and was buried in the church of St. Giles, Cripplegate. His funeral was attended by "his learned and great Friends in London, not without a friendly concourse of the

Vulgar."6 A monument to Milton rests in Poets' Corner at Westminster Abbey.

- Flannagan, Roy C. "Chronology". Paradise Lost. Macmillan, 1992.

- Parker, William Riley. Milton: A Biography. vol 1.

Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1996. 288.

- Masson, David. "A Brief Life of Milton." Encyclopaedia Britannica, 9th ed, 1888.

Excerpted in: Milton, John. Paradise Lost. Scott Elledge, ed.

New York, W. W. Norton & Company, 1993. 329-330.

- Parker. 345.

- Masson. 346.

- John Toland in 1698, quoted in Exploring Poetry, The Gale Group, 2006.

Selected Bibliography

Biographical

- Brown, Cedric. John Milton: A Literary Life. New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 1995.

- Campbell, Gordon, ed. A Milton Chronology. New York: Macmillan, 1997.

- Darbishire, Helen, ed. The Early Lives of Milton.

London: Constable & Co., 1932. (Repr. 1965)

Reprinted, Scholarly Press, 1971.

- Diekhoff, John. Milton on Himself: Milton's Utterances Upon Himself and His Works.

Oxford: OUP, 1939. Reprinted, London: Cohen & West, 1965.

- Fletcher, Harris F. The Intellectual Development of John Milton. 2 vols.

Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 1956-1961.

- French, Joseph M., ed. The Life Records of John Milton. 5 vols.

New Brunswick, NJ: Rutgers University Press, 1949-58.

Reprinted, New York: Gordian Press, 1966.

- Hanford, James H. John Milton, Englishman. New York: Crown Publishers, 1949.

- Lewalski, Barbara K. The Life of John Milton: A Critical Biography.

Williston, VT: Blackwell Publishers, 2001.

- Masson, David. The Life of John Milton. 7 vols. London: Macmillan, 1859-94.

- Parker, William R. Milton: A Biography. 2 vols. 2nd ed. rev.

Gordon Campbell, Ed. Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1996.

- Shawcross, John T. John Milton: The Self and the World.

Lexington: University Press of Kentucky, 1993. (Repr. 2001)

- Wilson, A.N. The Life of John Milton. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1983. (Repr. 1996)

Collected Works

- Ayers, Robert W., ed. The Complete Prose Works of John Milton. Revised Ed.

New Haven: Yale University Press, 1980.

- Bush, Douglas. The Portable Milton. New York: Viking Penguin, 1976.

- Flannagan, Roy C., ed. The Riverside Milton. Boston: Houghton Mifflin, 1998.

- Hughes, Merritt Y., ed. John Milton: Complete Poems and Major Prose.

New York: Odyssey Press, 1957.

- Patterson, Frank A., ed. The Works of John Milton. 20 vol.

New York: Columbia University Press, 1931–40.

- Shawcross, John T., ed. The Complete Poetry of John Milton. Revised Ed.

New York: Anchor Books, 1971.

Selected Studies

- Armitage, David, Armand Himy, and Quentin Skinner, eds. Milton and Republicanism. Cambridge: CUP, 1995.

- Cummins, Juliet, ed. Milton and the Ends of Time. Cambridge: CUP, 2003.

- Daiches, David. Milton. Reprint. New York: W. W. Norton & Co., 1966.

- Danielson, Dennis. The Cambridge Companion to Milton. 2nd ed. Cambridge: CUP, 1999.

- Dobranski, Stephen B., and John P. Rumrich, eds. Milton and Heresy. Cambridge: CUP, 1998.

- Evans, Martin J., ed. John Milton: Twentieth Century Perspectives. 5 vols.

New York: Taylor & Francis (Routledge), 2002.

- Fallon, Stephen M. Milton among the Philosophers: Poetry and Materialism in Seventeenth-Century England.

Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press, 1991.

- Ferry, Anne D. Milton's Epic Voice: The Narrator in Paradise Lost. Reprint.

Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1983.

- Flannagan, Roy C. John Milton: A Short Introduction. Oxford: Blackwell Publishers, 2002.

- Freeman, James A. Milton and the Martial Muse: Paradise Lost and European Traditions of War.

Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1980.

- Geisst, Charles R. The Political Thought of John Milton. London: Macmillan, 1984.

- Hunter, William Bridges, C. A. Patrides and J. H. Adamson, eds.Bright Essence: Studies in Milton's Theology.

Salt Lake City: University of Utah Press, 1971.

- Kermode, Frank, ed. The Living Milton: Essays by Various Hands. Reprint.

London: Routledge & Kegan Paul, 1960.

- Lieb, Michael and John T. Shawcross, eds. Achievements of the Left Hand: Essays on the Prose of John Milton.

Amherst: University of Massachussetts Press, 1974.

- Luxon, Thomas H. Single Imperfection: Milton, Marriage and Friendship.

Pittsburgh: Duquesne University Press, 2005.

- Marjara, Harinder Singh. Contemplation of Created Things: Science in Paradise Lost.

Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 1992.

- Nicholson, Marjorie. John Milton: A Reader's Guide to his Poetry

New York: Farrar, Straus & Giroux, 1963.

- Patrides, C.A. Milton and the Christian Tradition. Oxford: OUP, 1966.

- Patrides, C.A., ed. Milton's Epic Poetry: Essays on 'Paradise Lost' and 'Paradise Regained'.

London: Penguin Books, 1967.

- Revard, Stella P. The War in Heaven: "Paradise Lost" and the Tradition of Satan's Rebellion.

Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 1980.

- Shawcross, J. T., ed. Milton: The Critical Heritage. London: Routledge & Kegan Paul, 1970.

- Steadman, John M. Milton and the Paradoxes of Renaissance Heroism.

Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press, 1987.

- Steadman, John M. Milton's Epic Characters.

Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1968.

- Tillyard, E. M. W. Studies in Milton. London: Chatto & Windus, 1951.

To cite this article:

Jokinen, Anniina. "Life of John Milton." Luminarium.

21 June 2006. [Date you accessed this article].

<http://www.luminarium.org/sevenlit/milton/miltonbio.htm>

|

Back to Milton |

Site copyright ©1996-2012 Anniina Jokinen. All Rights Reserved.

Page created by Anniina Jokinen on June 21, 2006. Last updated April 14, 2012.

|

|

|