|

|

|

|

By Dr. Wayne Narey, Arkansas State University

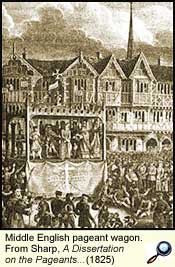

The old Medieval stage of "place-and-scaffolds," still in use in Scotland in the early sixteenth century, had fallen into disuse; the kind of temporary stage that was dominant in

England about 1575 was the booth stage of the marketplace—a small rectangular

stage mounted on trestles or barrels and "open" in the sense of being

surrounded by spectators on three sides.

The old Medieval stage of "place-and-scaffolds," still in use in Scotland in the early sixteenth century, had fallen into disuse; the kind of temporary stage that was dominant in

England about 1575 was the booth stage of the marketplace—a small rectangular

stage mounted on trestles or barrels and "open" in the sense of being

surrounded by spectators on three sides.

The stage proper of the

booth stage generally measured from 15 to 25 ft. in width and from 10 to 15 ft.

in depth; its height above the ground averaged a bout 5 ft. 6 in., with

extremes ranging as low as 4 ft. and as high as 8 ft.; and it was backed by a

cloth-covered booth, usually open at the top, which served as a tiring-house

(short for "attiring house," where the actors dressed).

In the England of 1575

there were two kinds of buildings, designed for functions other than the acting

of plays, which were adapted by the players as temporary outdoor playhouses:

the

animal-baiting rings or "game houses" (e.g. Bear Garden) and the

inns.  Presumably, a booth stage was set up against a wall at one side of the

yard, with the audience standing in the yard surrounding the stage on three sides.

Out of these "natural"

playhouses grew two major classes of permanent Elizabethan playhouse,

"public" and "private." In general, the public playhouses were large

outdoor theatres, whereas the private playhouses were smaller indoor theatres. The maximum capacity of a typical public

playhouse (e.g., the Swan) was about 3,000 spectators; that of a typical

private playhouse (e.g., the Second Blackfriars), about 700 spectators. Presumably, a booth stage was set up against a wall at one side of the

yard, with the audience standing in the yard surrounding the stage on three sides.

Out of these "natural"

playhouses grew two major classes of permanent Elizabethan playhouse,

"public" and "private." In general, the public playhouses were large

outdoor theatres, whereas the private playhouses were smaller indoor theatres. The maximum capacity of a typical public

playhouse (e.g., the Swan) was about 3,000 spectators; that of a typical

private playhouse (e.g., the Second Blackfriars), about 700 spectators.

At the public playhouses the

majority of spectators were "groundlings" who stood in the dirt yard for a

penny; the remainder were sitting in galleries and boxes for two pence or more.

At the private playhouses all spectators were seated (in pit, galleries, and

boxes) and paid sixpence or more. In the beginning, the private playhouses were

used exclusively by Boys' companies, but this distinction disappeared about

1609 when the King's Men, in residence at the Globe in the summer, began using

the Blackfriars in winter.

At the public playhouses the

majority of spectators were "groundlings" who stood in the dirt yard for a

penny; the remainder were sitting in galleries and boxes for two pence or more.

At the private playhouses all spectators were seated (in pit, galleries, and

boxes) and paid sixpence or more. In the beginning, the private playhouses were

used exclusively by Boys' companies, but this distinction disappeared about

1609 when the King's Men, in residence at the Globe in the summer, began using

the Blackfriars in winter.

Originally the private

playhouses were found only within the City of London (the Paul's Playhouse, the First and

Second Blackfriars), the public playhouses only in the suburbs (the Theatre,

the Curtain, the Rose, the Globe, the Fortune, the Red Bull); but this

distinction disappeared about 1606 with the opening of the Whitefriars

Playhouse to the west of Ludgate.

Public-theatre audiences,

though socially heterogeneous, were drawn mainly from the lower classes—a

situation that has caused modern scholars to refer to the public-theatre

audiences as "popular"; whereas private-theatre audiences tended to consist

of gentlemen (those who were university educated) and nobility; "select"

is the word most usually opposed to "popular" in this respect.

James Burbage, father to

the famous actor Richard Burbage of Shakespeare's company, built the first

permanent theatre in London,

the Theatre, in 1576. He probably merely adapted the form of the baiting-house

to theatrical needs. To do so he built a large round structure very much like a

baiting-house but with five major innovations in the received form.

First, he paved the ring

with brick or stone, thus paving the pit into a "yard."

Second, Burbage erected a

stage in the yard—his model was the booth stage of the marketplace, larger than

used before, with posts rather than trestles.

Third, he erected a

permanent tiring-house in place of the booth. Here his chief model was the

passage screens of the Tudor domestic hall. They were modified to withstand the

weather by the insertion of doors in the doorways. Presumably the tiring-house,

as a permanent structure, was inset into the frame of the playhouse rather

than, as in the older temporary situation of the booth stage, set up against

the frame of a baiting-house. The gallery over the tiring-house (presumably

divided into boxes) was capable of serving variously as a "Lord's

room" for privileged or high-paying spectators, as a music-room, and as a

station for the occasional performance of action "above" as, for

example, Juliet's balcony.

Fourth, Burbage built a

"cover" over the rear part of the stage, called "the Heavens", supported

by posts rising from the yard and surmounted by a "hut."

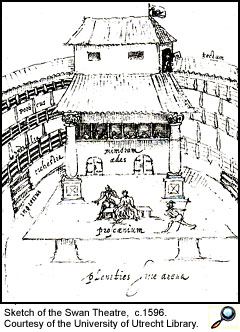

And fifth, Burbage added a

third gallery to the frame. The theory of origin and development suggested in

the preceding accords with our chief pictorial source of information about the

Elizabethan stage, the "De Witt" drawing of the interior of the Swan

Playhouse (c. 1596).

It seems likely that most

of the round public playhouses—specifically, the Theatre (1576), the Swan

(1595), the First Globe (1599), the Hope (1614), and the Second Globe

(1614)—were of about the same size.

The Second Blackfriars Playhouse of 1596 was designed by James Burbage, and he built his playhouse in

the upper-story Parliament Chamber of the Upper Frater of the priory. The

Parliament Chamber measured 100 ft. in length, but for the playhouse Burbage

used only two-thirds of this length. The room in question, after the removal of

partitions dividing it into apartments, measured 46 ft. in width and 66 ft. in

length. The stage probably measured 29 ft. in width and 18 ft. 6 in. in depth.

To cite this article:

Narey, Wayne. "Elizabethan Playhouses." Luminarium.

2 Aug 2006. [Date you accessed this article].

<http://www.luminarium.org/renlit/dramavenues.htm>

Continue to:

English Drama: From Medieval to Renaissance

The Sociopolitical Climate

in Elizabethan England

Elizabethan World View

Elizabethan Playhouses

Elizabethan Staging

Conventions

Timeline of Elizabethan Playhouses and Acting Companies

| to Renaissance Drama

|

| to Renaissance Literature

|

Site copyright ©1996-2010 Anniina Jokinen. All rights reserved.

This page created by Anniina Jokinen on August 2, 2006. Last updated August 10, 2010.

|

|

|