|

|

|

The Pardoners in the Middle Ages

Excerpted from:

Jusserand, J.J. English Wayfaring Life in the Middle Ages. 8th Ed.

London: T. Fisher Unwin, 1891. 311-337.

* * * * *

Little by little the idea of a commutation vanished, and was replaced by quite a different system, known as the theory of the "treasury." It had indeed become obvious as the use of indulgences spread that they could no longer be justified as offering to the sinner nothing more than his choice between several sorts of penance. They were something else. A short prayer, a small gift in money, would exempt devout people from the greatest penalties and from numberless years of a possible purgatory; the one could scarcely be considered as being the equivalent of the other; how was the equilibrium established between the two scales? The answer was that the deficiency was made up by the application to the sinner of merits, not indeed his own, but merits of Christ, the Virgin, and the saints, of which there was an inexhaustible "treasury," the dispensation of which rested with the Pope and the clergy. This theory was acted upon long before it was put forth in express words; it does not appear to have been more than vaguely alluded to before the fourteenth century, when Pope Clement VI., "Doctor Doctorum," gave a perfectly clear definition and exposition of the "treasury" system. In a bull of the year 1350, Clement explains that the merits of Christ are infinite, and the merits of the Virgin and the saints are superabunding. This excess of unemployed merit has been constituted into a treasury,

"not one that is deposited in a strong room, or concealed in a field, but which is to be usefully distributed to the faithful, through the blessed Peter, keeper of heaven's gate, and his successors." However largely employed, there ought to be "no fear of an absorption or a diminution of this treasury, first on account of the infinite merits of Christ, as has been said before, then because the more numerous are the people reclaimed through the use of its contents, the more it is augmented by the addition of their merits." 1 It must be admitted that such being the case no doubt the treasury would never be found empty, since the more was drawn from it, the more it grew. Such is in all its simplicity the theory of the "treasury," which has ever since, and with no change whatever, been acted upon.

Having so much wealth to distribute among the faithful, the Church used to insure its repartition through means of certain people who went about, authorized by official letters, offering to good Christians some particle of the heavenly wealth placed at the disposal of the successors of St. Peter. They expected in return some part of the much more worldly riches their hearers might be possessed of, and which could be applied to more tangible uses than the "treasury." The men entrusted with this mission were called sometimes quæstors, on account of what they asked, and sometimes pardoners, on account of what they gave.

Does not the name of these strange beings, whose character is peculiar to the Middle Ages much more than that of the friars, or any of those whom we have just studied, recall the sparkling laugh of Chaucer, and bring back his amusing portrait to the memory? His pardoner describes himself:

"Lordyngs, quod he, in chirches whan I preche,

I peyne me to have an hauteyn speche,

And ryng it out, as lowd as doth a belle,

For I can al by rote which that I telle.

My teeme is alway oon, and ever was;

Radix omnium malorum est cupiditas."

|

In the pulpit he leans to the right, to the left, he gesticulates, he babbles; his arms move as much as his

tongue; it is a wonder to see and hear him.

"I stonde lik a clerk in my pulpit,

And whan the lewed people is doun i-set,

I preche so as ye have herd before,

And telle hem an hondred japes more.

Than peyne I me to strecche forth my necke

And est and west upon the poeple I bekke,

As doth a dowfe, syttyng on a berne;

Myn hondes and my tonge goon so yerne,

That it is joye to se my businesse.

* * * * *

I preche no thyng but of coveityse.

Therfor my teem is yit, and ever was,

Radix omnium malorum est cupiditas."

|

This description seems to-day so extraordinary that it is well worth inquiring whether or not it is consistent with facts, and can be verified from authentic sources. The search for documents on the subject will show once more the marvellous exactness of Chaucer's pictures; however malicious they may be when they concern the pardoner, they do not contain a trait that may not be justified by letters emanating from papal or episcopal chancery.

These quæstores, or quæstiarii as they were officially called, were, so says Boniface IX., speaking at the very time that the poet wrote his tales, sometimes secular priests and sometimes friars, but extremely impudent. They dispensed with all ecclesiastic licence, and went from hamlet to hamlet delivering speeches, showing their relics and selling their pardons. It was a lucrative trade, and the competition was great; the success of the authorized pardoners had caused a crowd of interested pardoners to issue from the schools or the priory, or from mere nothingness, greedy, with glittering eyes, as in the "Canterbury Tales": "suche glaryng eyghen hadde he as an hare;" true vagabonds, infesters of the highroads, who having nothing to care for, boldly carried on their impostor's traffic. They imposed it, spoke loud, and without scruple unbound upon earth all that might be bound in heaven. Much profit arose from this; Chaucer's pardoner gained a hundred marks a year, which might easily be, since, having asked no authority from any one he gave no one any accounts, and kept all the gains to himself. In his measured language the Pope tells us as much as the poet, and it seems as though he would recommence, feature for feature, the portrait drawn by the old storyteller. First, says the pontifical letter, these pardoners swear that they were sent by the Court of Rome: "Certain religious, who even belong to different mendicant orders, and some secular clerks, occasionally advanced in the ecclesiastical hierarchy, affirm that they are sent by us or by the legates or the nuncios of the apostolic see, and that they have received the mission to treat of certain affairs, ... to receive money for us and the Roman Church, and they go about the country under these pretexts." We find in the same manner that it is Rome whence Chaucer's personage comes, and he is always speaking against avarice:

"a gentil pardoner

* * * * *

That streyt was comen from the court of Rome

* * * * *

His walet lay byforn him in his lappe,

Bret-ful of pardoun come from Rome al hoot."

* * * * *

"What! trowe ye, whiles that I may preche

And wynne gold and silver for I teche,

That I wil lyve in povert wilfully?

* * * * *

For I wol preche and begge in sondry londes,

I wil not do no labour with myn hondes,

* * * * *

I wol noon of thapostles counterfete

I wol have money, wolle, chese, and whete."

|

"Thus," continues the Pope, "they proclaim to the faithful and simple people the real or pretended authorizations which they have received; and irreverently abusing those which are real, in pursuit of infamous and hateful gain, consummate their impudence by attributing to themselves false and pretended authorizations of this kind."

What says the poet? That the charlatan has always fine things to show, that he knows how to dazzle the simple that he has his bag full of parchments with respect-worthy seals, true or false no doubt; that the people look on and admire, that the curate gets angry but holds his tongue:

"First I pronounce whennes that I come,

And thanne my bulles schewe I alle and some:

Oure liege lordes seal upon my patent

That schewe I first, my body to warent,

That no man be so hardy, prest ne clerk,

Me to destourbe of Cristes holy werk.

And after that than tel I forth my tales.

Bulles of popes and of cardynales,

Of patriarkes, and of bisshops, I schewe.

And in Latyn speke I wordes fewe

To savore with my predicacioun,

And for to stere men to devocioun."

|

And that "turpem et infamem quæstum" of which the pontiff makes mention is not forgotten:

"Now good men, God foryeve yow your trespas,

And ware yow fro the synne of avarice.

Myn holy pardoun may you alle warice,

So that ye offren noblis or starlinges,

Or elles silver spones, broches, or rynges.

Bowith your hedes under this holy bulle."

|

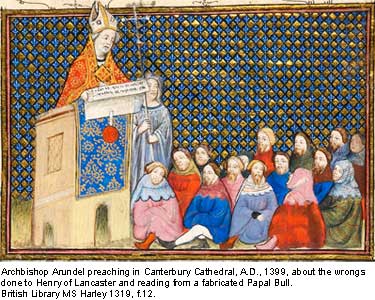

The effect of large parchments and large seals displayed from the pulpit scarcely ever failed upon the simple people assembled, and in many circumstances of more importance than retail selling of the merits of saints in heaven, recourse was had to such performances. Thus when Henry of Lancaster [afterwards King Henry IV] came to turn his cousin Richard II. out of the English throne, the first thing he did, according to Créton, was to have a papal bull carried up the pulpit of Canterbury Cathedral by the Archbishop himself, the text being read and commented upon by the prelate.

As Créton was not present when this scene, which he describes only on hearsay, took place, the speech he gives is the more interesting for our purpose for it may be considered an average speech, such a one as was usual and likely to have been pronounced on the occasion. It is to the following effect:

"My good people, hearken all of you here: you well know how the king most wrongfully and without reason has banished your lord Henry; I have therefore obtained of the holy father who is our patron, that those who shall forthwith bring aid this day, shall every one of them have remission of all sins whereby from the hour of their baptism they have been defiled. Behold the sealed bull that the Pope of renowned Rome hath sent me, my good friends, in behalf of you all. Agree then to help him to subdue his enemies, and you shall for this be placed after death with those who are in Paradise."

"Then," continues the narrator, describing the effect of the speech, "might you have beheld young and old, the feeble and the strong, make a clamour, and regarding neither right or wrong, stir themselves up with one accord; thinking that what was told them was true, for such as they have little sense or knowledge. The archbishop invented this device . . ."2

Supposed or real, this speech is given by Créton as having been delivered in good earnest, and is fit to be compared to the pardoner's in Chaucer's tale. The Canterbury pilgrim's burst of eloquence may be taken as a caricature, but not an unrecognizable one of the grave discourses such as the one we have just heard.

The parallel may be continued farther. The apostolic letter before alluded to goes on: "For some insignificant sum of money, they extend the veil of a lying absolution not over penitents, but over men of a hardened conscience who persist in their iniquity, remitting, to use their own words, horrible crimes without there having been any contrition nor fulfilment of any of the prescribed forms." Chaucer's pardoner acts in the very same manner, and says:

"I yow assoile by myn heyh power,

If ye woln offre, as clene and eek as cler

As ye were born.

* * * * *

I rede that oure hoste schal bygynne,

For he is most envoliped in synne.

Come forth, sire ost, and offer first anoon,

And thou schalt kisse the reliquis everichoon,

Ye for a grote; unbocle anone thi purse."3

|

Boccaccio in one of the novels which he is supposed to tell himself, under the name of Dioneo, produces an ecclesiastic who has the greatest resemblance, moral and physical, to Chaucer's man. He is called Frà Cipolla, and was accustomed to visit Certaldo, Boccaccio's village. "This Frà Cipolla was little of person, red-haired and merry of countenance, the jolliest rascal in the world, and to boot, for all he was no scholar, he was so fine a talker and so ready of wit that those who knew him not would not only have esteemed him a great rhetorician, but had avouched him to be Tully himself, or maybe, Quintilian; and he was gossip, or friend, or well-wisher, to well-nigh every one in the country." If his hearers give him a little money or corn or anything, he will show them the most wonderful relics; and besides they will enjoy the special protection of the patron saint of his order, St. Anthony: "Gentlemen and ladies, it is, as you know, your usance to send every year to the poor of our lord Baron St. Anthony of your corn and of your oats, this little and that much, according to his means and his devoutness, to the intent that the blessed St. Anthony may keep watch over your beeves and asses and swine and sheep; and, beside this, you use to pay, especially such of you as are inscribed into our company, that small due which is payable once a year."4

One may conceive that such people had few scruples and knew how to profit by those of others. They released their clients from all possible vows, remitted all penances, for money. The more prohibitions, obstacles, or penances were imposed, the more their affairs prospered; they passed their lives in undoing what the real clergy did, and that without profit to any one but themselves. The Pope again tells us:

"For a small compensation they release you from vows of chastity, of abstinence, of pilgrimage beyond the sea to Sts. Peter and Paul of Rome, or to St. James of Compostella, and any other vows." They allow heretics to re-enter the bosom of the Church, illegitimate children to receive sacred orders, they take off excommunications, interdicts; in short, as their power comes from themselves alone, nothing forces them to restrain it and they take it fully and without stint; they recognize no superiors and thus remit little and great penances. Lastly, they affirm that "it is in the name of the apostolic chamber that they take all this money, and yet they are never seen to give an account of it to any one: 'Horret et merito indignatur animus talia reminisci.'"5

They went yet further, they had formed regular associations for systematically speculating in the public confidence; thus Boniface IX. orders in the year 1390, that the Bishops should make an inquiry into everything that concerns these "religious or secular priests, their people, their accomplices, and their associations"; that they should imprison them "without other form of law; de piano ac sine strepitu et figura judicii;" should make them render accounts, confiscate their receipts, and if their papers be not in order hold them under good keeping, and refer the matter to the sovereign pontiff.

There were indeed authorized pardoners who paid the produce of their receipts into the treasury of the Roman Court. The learned Richard d'Angerville (or de Bury), Bishop of Durham, in a circular of December 8, 1340, speaks of apostolic or diocesan letters subject to a rigorous visa, with which the regular pardoners were furnished.6 But many did without them, and the Bishop notices one by one the same abuses as the Pope and as Chaucer. "Strong complaints have come to our ears that the questors of this kind, not without great and rash boldness, of their own authority, and to the great danger of the souls who are confided to us, openly making game of our power, distribute indulgences to the people, dispense with the execution of vows, absolve the perjured, homicides, usurers, and other sinners who confess to them; and, for a little money paid, grant remission for crimes ill-atoned for, and are given to a multitude of other abuses."

Henceforward all curates and vicars must refuse to admit these pardoners to preach or to give indulgences, whether in the Churches or anywhere else, if they be not provided with letters or a special licence from the Bishop himself. And this was a most proper injunction, for with these bulls brought from far-off lands, furnished with unknown seals "of popes and of cardynales, of patriarkes and of bisshops,"7 it was too easy to make people believe that all was in order. Meanwhile let all those who are now wandering round the country be stripped of what they have taken, and let "the money and any other articles collected by them or on their behalf" be seized.

The common people not always having pieces of money, Chaucer's pardoner contented himself with "silver spones, broches, or rynges;" besides, we find here a new allusion to those associations of pardoners which must have been so harmful. They employed inferior agents; the general credulity and the widespread wish to get rid of religious trammels which men had imposed on themselves, or which had been imposed on them on account of their sins, were a mine for the perverse band, the veins of which they carefully worked. By means of these subordinate representatives of their imaginary power, they easily extended the field of their operations; and the complicated threads of their webs traversed the whole kingdom, sometimes too strong to be broken, sometimes too subtle to be perceived.

Occasionally, too, the bad example came from very high quarters; all had not the Bishop of Durham's virtue. Walsingham relates with indignation the conduct of a cardinal who made a stay in England in order to negociate a marriage between Richard II. and the emperor's sister. For money this prelate, like the pardoners, took off excommunications, dispensed with pilgrimages to St. Peter, St. James, or Jerusalem, and had the sum that would have been spent on the journey given to him, according to an estimate;8 and it is much to be regretted from every point of view that the curious tariff of the expenses of a journey thus estimated has not come down to us.

The list of the misdeeds of pardoners was in truth enormous, and it is found even larger on exploring the authentic ecclesiastical documents than in the poems of Chaucer himself. Thus in a bull of Pope Urban V., dated 1369, we find the description of practices which seem to have been unknown to the otherwise experienced

"gentil pardoner of Rouncival." These doings were familiar to the pardoners employed by the hospital of St. John of Jerusalem in England. They pretended to have received certain immunities by which they could dispence with apostolic letters, and were not bound to show any in order to be allowed to make their preachings and to offer to the people their "negotia quaestuaria." The parish rectors and curates naturally objected to such pretensions, but their complaints were badly received, and to get rid of such tenacious adversaries, the pardoners sued them before some distant judge for contempt of their cloth and privileges. While the suit was being determined they remained free to act pretty much as they liked. Sometimes they were so happy as to obtain a condemnation against the priest who had tried to do his duty by them, and even succeeded in having him excommunicated: which could of course but be a cause of great merriment among the unholy tribe.

"Very often, also," adds Pope Urban, "when they mean to hurt a rector or his curate, they go to his church on some feast-day, especially at such time as the people are accustomed to come and make their offerings. They begin then to make their collections or to read the name of their brotherhood or fraternity, and continue until such an hour as it is not possible to celebrate mass conveniently that day. Thus they manage perversely to deprive these rectors and vicars of the offerings which accrue to them at such masses." They have, on the other hand, Divine service performed "in polluted or interdicted places, and there also bury the dead; they use, as helps to their trade, almost illiterate subordinates, who spread errors and fables among the people."9

Such abuses and many others, constantly pointed out by councils, popes, and bishops, moved the University of Oxford to recommend, in the year 1414, the entire suppression of pardoners, as being men of loose life and lying speeches, spending their profits "with the prodigal son," remitting to sinners their sins as well as their penances, encouraging sin by the ease of their absolutions, and drawing the souls of simple people "to Tartarus." But this request was not listened to, and pardoners continued to prosper for the moment.10

At the same time that they sold indulgences, the pardoners showed relics. They had been on pilgrimage and had brought back little bones and fragments of all kinds, of holy origin, they said. But although there were credulous persons among the multitude, among the educated class the disabused were not wanting who scoffed at the impertinence of the impostors without mercy. The pardoners of Chaucer and Boccaccio, and in the sixteenth century of Heywood and Lyndsay,11 had the pleasantest relics. The Chaucerian who possessed a piece of the sail of St. Peter's boat, is beaten by Frate Cipolla, who had received extraordinary relics at Jerusalem. "I will, as an especial favour, show you," said he, "a very holy and goodly relic, which I myself brought aforetime from the Holy Lands beyond seas, and that is one of the Angel Gabriel's feathers, which remained in the Virgin Mary's chamber, whenas he came to announce to her in Nazareth!"12

The feather, which was a feather from the tail of a parrot, through some joke played upon him was replaced in the casket of the holy man by a few coals; when he perceived the metamorphosis he did not show any surprise, but began the narrative of his long voyages, and explained how, instead of the feather, the coals on which St. Lawrence was grilled would be seen in his coffer. He received them from " My lord Blamemenot Anitpleaseyou," the worthy patriarch of Jerusalem, who also showed him "a finger of the Holy Ghost as whole and sound as ever it was, . . . and one of the nails of the cherubim, . . . divers rays of the star that appeared to the three Wise Men in the East, and a vial of the sweat of St. Michael when as he fought with the devil;" he possessed also "somewhat of the sound of the bells of Solomon's Temple in a vial."

These are poets' jests, but they are less exaggerated than might be thought. Was there not shown to the pilgrims at Exeter a bit "of the candle which the angel of the Lord lit in Christ's tomb"? This was one of the relics brought together in the venerable cathedral by Athelstan, "the most glorious and victorious king," who had sent emissaries at great expense on to the Continent to gather these precious spoils. The list of their discoveries, which has been preserved in a missal of the eleventh century, comprises also a little of "the bush in which the Lord spoke to Moses," and a lot of other curiosities.13

Matthew Paris relates that in his time the friar preachers gave to Henry III. a piece of white marble on which there was the trace of a human foot. According to the testimony of the inhabitants of the Holy Land this was nothing less than the mark of one of the Saviour's feet, a mark which He left as a souvenir to His apostles after His Ascension. "Our lord the king had this marble placed in the church of Westminster, to which he had already lately offered some of the blood of Christ."14

In the fourteenth century kings continued to give example to the common people, and to collect relics of doubtful authenticity. In the accounts of the expenses of Edward III., in the thirty-sixth year of his reign, we find that he paid a messenger a hundred shillings for bringing a gift of a vest which had belonged to St. Peter.15

In France, at the same period, the wise King Charles V. had one day the curiosity to visit the cupboard of the Sainte Chapelle, where the relics of the passion were kept. He found there a phial with a Latin and Greek inscription indicating that it contained a portion of the blood of Jesus Christ. "Then," relates Christine de Pisan, "that wise king, because some doctors have said that, on the day that our Lord rose, nothing was left on earth of His worthy body that was not all returned into Him, would hereupon know and inquire by learned men, natural philosophers, and theologians, whether it could be true that upon earth there were some of the real pure blood of Jesus Christ. Examination was made by the said learned men assembled about this matter; the said phial was seen and visited with great reverence and solemnity of lights, in which when it was hung or lowered could be clearly seen the fluid of the red blood flow as freshly as though it had been shed but three or four days since: which thing is not small marvel, considering the passion was so long ago. And these things I know for certain by the relation of my father who was present at that examination, as philosophic officer and counsellor of the said prince."

After this examination made by great

"solemnity of lights," the doctors declared themselves for the authenticity of the miracle;16 which was not in reality more surprising than that at Naples Cathedral, where even now, the blood of the patron saint of the town may be seen to liquify several times a year, and for several days each time.

In every country of Europe the pardoners enjoyed exactly the same reputation and acted in the same manner. We may turn to France, to Germany, to Italy, to Spain, and we find them living, so long as there remained any, as Chaucer's pardoner did.

* * * * *

They lingered on till the sixteenth century, and then were entirely suppressed in the twenty-first session of the oecumenical council of Trent, July 16, 1562, Pius IV. being Pope. It is stated in the ninth chapter of the "Decree of Reform," published in that session, that "no further hope can be entertained of amending" such pardoners (eleemosynarum quæstores), therefore "the use of them and their name are entirely abolished henceforth in all Christendom."17

1. See Appendix XIII.

2. "Archaeologia," Vol. xx. p. 53, John Webb's translation. See Appendix XIV.

3. "The Poetical Works of Chaucer," ed. Richard Morris, Prologue to "Canterbury Tales," vol. ii. p. 21,

and Prologue to "Pardoner's Tale," vol. iii. pp. 86-90.

4. "The Decameron of Giovanni Boccaccio" . . . done into English ... by John Payne, London, 1886, vol. ii. p. 278,

tenth Tale, sixth Day.

5 See Appendix XV.

6. See same Appendix.

7. Pardoner's Prologue.

8. "Excommunicatis gratiam absolutionis impendit. Vota peregrinationis ad apostolorum limina, ad Terram Sanctam,

ad Sanctum Jacobum non prius remisit quam tantam pecuniam recepisset, quantam, juxta veram aestimationem,

in cisdem peregrinationibus expendere debuissent, et ut cuncta concludam brevibus, nihil omnino petendum erat,

quod non censuit, intercedente pecunia concedendum" ("Historia Anglicana"; Rolls Series, vol. i. p. 452).

9. See Appendix XV.

10. See Appendix XV.

11. Lyndsay, "A Satire of the Thrie Estates" (performed 1535), Early English Text Society; John Heywood,

"The Pardoner and the Frere, the Curate and Neybour Pratte," 1533; "The foure Ps," 1545.

12 Payne's "Boccaccio," vol ii. pp, 280, 287.

13. "The Leofric Missal" (1050-1072) edited by F. E. Warren, 1883 (Clarendon Press), pp. lxi, 3, 4.

14 "Historia Anglorum" (Historia minor), ed., Sir F. Madden, London, 1866; vol. iii. p. 60 (Rolls Series).

15. * Devon's "Issues of the Exchequer," 1837, p. 176.

16. "Le livre des fais et bonnes moeurs du sage roy Charles," by Christine de Pisan, chap, xxxiii. vol. i. p. 633;

"Nouvelle Collection de Mémoires," ed. Michaud et Poujoulat, Paris, 1836.

17. '"Conciliorum generalium ecclesiae catholicae," tomus iv. p. 261,

Pauli V. Pont. max. auctoritate editus, Rome, 1623. See Appendix XV.

Source:

Jusserand, J. J. English Wayfaring Life in the Middle Ages. 8th Ed.

London: T. Fisher Unwin, 1891. 311-337.

| to Essays and Articles on Chaucer |

This page was created by Anniina Jokinen on November 11, 2009. Last updated January 8, 2023

|

|

Middle English Literature

Geoffrey Chaucer

John Gower

Sir Gawain and the Green Knight

William Langland / Piers Plowman

Julian of Norwich

Margery Kempe

Thomas Malory / Morte D'Arthur

John Lydgate

Thomas Hoccleve

Paston Letters

Everyman

Medieval Plays

Middle English Lyrics

Essays and Articles

Intro to Middle English Drama

Sciences

Medieval Cosmology

Historical Events and Persons

Hundred Years' War (1337-1453)

Edward III

Edward, Black Prince of Wales

Lionel of Antwerp, Duke of Clarence

John of Gaunt, Duke of Lancaster

Edmund of Langley, Duke of York

Thomas of Woodstock, Gloucester

Richard of York, E. of Cambridge

Richard II

Henry IV

Edward, Duke of York

Henry V

Thomas, Duke of Clarence

John, Duke of Bedford

Humphrey, Duke of Gloucester

Catherine of Valois

Charles VII, King of France

Joan of Arc

Louis XI, King of France

Charles the Bold, Duke of Burgundy

The Wars of the Roses (1455-1485)

Causes of the Wars of the Roses

The House of Lancaster

The House of York

The House of Beaufort

The House of Neville

Henry VI

Margaret of Anjou

Richard Plantagenet, Duke of York

Edward IV

Elizabeth Woodville

Edward V

Richard III

George, Duke of Clarence

More at Encyclopedia and at

Additional Medieval Sources

|

|