|

|

|

PILGRIMAGE OF GRACE, a name assumed by religious insurgents in the north of England, who opposed the dissolution of the monasteries. The movement, which commenced in Lincolnshire in Sept. 1536, was suppressed in Oct., but soon after revived in Yorkshire; and an expedition bearing the foregoing name, having banners on which were depicted the five wounds of Christ, was headed by Robert Aske and other gentlemen [cf. Lord Darcy and Robert Constable], and joined by priests and 40,000 men of York, Durham, Lancaster, and other counties. They took Hull and York, with smaller towns. The Duke of Norfolk marched against them, and by making terms dispersed them [see 24 Articles]. Early in 1537 they again took arms, but were promptly suppressed, and the leaders, several abbots, and many others were executed.

Text source:

Haydn's Dictionary of Dates. 17th Ed. Benjamin Vincent, ed.

New York: Harper & Brothers, 1883. 530.

PILGRIMAGE OF GRACE

By J. Franck Bright

With the death of Catherine some of the dangers which threatened insurrection in England disappeared. It was no longer

impossible that Charles should be reconciled to his uncle [Henry VIII].

As the year therefore passed, the chances of an insurrection in England became less, and the real opportunity for successful action on the part of the

reactionary party was gone. But, perhaps because they felt that time was thus passing away, or because accidental circumstances led the way to an outbreak,

the discontented party, before the year was out, were in arms throughout the whole North of England. Nor did this party consist of one class alone. For one

reason or another, nearly every nobleman of distinction, and nearly every Northern peasant, alike joined in the movement.

The causes which touched the interests of so many different classes were of course various. There was indeed one tie which united them all. All, gentle and

simple, were alike deeply attached to the Roman Church, and saw with detestation the beginning of the Reformation in the late Ten Articles,

and the havoc which Cromwell and his agents were making among the monasteries. In fact, the coarseness with which the reforms

were carried out were very revolting. Stories were current of how the visitors' followers had ridden from abbey to abbey clad in the sacred vestments of

the priesthood, how the church plate had been hammered into dagger hilts. The Church had been always more powerful in the North, and the dislike to the

reforms was proportionately violent. But, apart from this general conservative feeling, each class had a special grievance of its own. The clergy, it is

needless to mention—they were exasperated to the last degree.

The nobles—always a wilder and more independent race than those of the South—saw with disgust the upstart Cromwell

the chief adviser of the Crown. They had borne the tyranny of Wolsey, but in Wolsey they could at least reverence the Prince of

the Church. They had even triumphed over Wolsey, and had probably believed that the older nobility would have regained some of their ancient influence. They

had been disappointed. Cromwell, a man of absolutely unknown origin, and with something at least of the downright roughness of a self-made man, was carrying

all before him.

The gentry, besides that they were largely connected with the superior clergy, and suffered with their suffering, were at the present smarting under a change

in the law, which deprived them of the power of providing for their younger children. By the common law it was not allowed to leave

landed property otherwise than to the eldest son or representative. To evade this it had been customary to employ what are called uses:—that is,

property was left to the eldest son, saddled with the duty of paying a portion, or sometimes the whole, of the rent to the use of the younger son. A long

continuance of this practice had produced inextricable confusion. There were frequently uses on uses, till at length it was often difficult to say

to whom the property really belonged. This difficulty had been met by the "Statute of Uses" in the preceding year, by which the holder of the use was

declared to be the owner of the property, and for his benefit a Parliamentary title was created. At the same time, to prevent a repetition of the difficulty,

i>uses were forbidden. Till, therefore, the law was altered a few years afterwards, the old common law held good, and, uses being impossible, gentry

with much land and little money were deprived of all power of helping their younger children.

The lower orders were suffering principally from a change in the condition of agriculture in England, for which the Government could not be held responsible.

There was a strong tendency to convert arable land into pasture. Complaints on this head are constant. Mercantile men also had begun to find that possession

of land gave them influence irrespective of birth. Bringing the mercantile spirit with them to the country, they had worked their properties to the best advantage,

regardless of the feelings of their tenants and labourers. The consequence was, that where in the old days there had been thriving villages, there were now in many

instances barren sheep-walks, supporting only two or three men. The rest of the old inhabitants, uprooted from their connection with the soil, thronged the towns,

or of necessity became dependent upon charity. They were suffering very deeply, and as usual attributed their sufferings to their governors.

The insurrection broke out in Lincolnshire, at Louth. Thither Heneage, one of the clerical commissioners, and the Bishop of Lincoln's chancellor were going on their

business on the 1st of October. It was rumoured that they intended to rob the treasury of the church. A crowd collected under the leading of a man who called himself

Captain Cobler. The church was locked and guarded, the great cross fetched out by way of standard, and the whole township marched to raise the neighbouring towns

and villages. The insurrection in Lincoln was essentially a popular one. It was on compulsion that the gentry joined it. There was a strong party for murdering them.

They were in fact besieged by the populace in the Close at Lincoln, and quickly threw their weight upon the side of the Government.

At Lincoln, during this quarrel between gentry and people, was a young lawyer, Robert Aske, who had been stopped by the insurgents, as he said,

returning to his work in London. However this may be, he at once imbibed the spirit of the insurrection, and hurried off into Yorkshire, where he had interest, and

where a rebellion of quite a different sort from that in Lincoln was quickly organized. The Lincolnshire rebels never came to open fighting. They sent a petition to

the King from Horncastle, begging that religious houses should be restored, the late subsidy remitted, the "Statute of Uses" be repealed, the villein blood[1]

removed from the Privy Council, and the heretic bishops[2] deprived.

The arrival of troops under Sir John Russell and the Duke of Suffolk was sufficient to cool the rebels' ardour,

and though they watched his progress sulkily, they did not absolutely oppose him. The ringleaders were given up and the insurrection dissolved. Suffolk had brought with

him the King's very firm answer to their petition: "How presumptuous," he says, "are ye, the rude commons of one shire, and that one of the most brute and beastly of the

whole realm and of least experience, to take upon you, contrary to God's law and man's law, to rule your Prince, whom ye are bound to obey and serve." He refused every

request.

It was the duty of the great nobles in each county, under such circumstances, to call out the military force of the county to repress the insurrection. Lord Hussey, in

Lincolnshire, had timorously held aloof and left the country. Lord Shrewsbury had gallantly taken his position at Nottingham. In

Yorkshire this duty would have devolved on Lord Darcy of Templehurst, an old and tried soldier of both the late and the present King. His sympathies were, however, wholly

with the movement, and, though Henry wrote to him to urge him to instant action, he threw himself with only twelve followers into Pontefract Castle, and there awaited the

arrival of the rebels. These had rendezvoused on Weighton Common, and having elected Aske general, and having despatched a force to Hull, moved

towards York. On the way they were joined by the Percies, with the exception of the Earl of Northumberland himself.

York surrendered to them. They then advanced to Pontefract, which was unable to hold out against them, and Lord Darcy and the Archbishop of

York speedily took the oath which was exacted of all whom the rebels met in their march. Lord Darcy henceforward became the leader of the movement, second only to Aske.

Of opposition in the North there was scarcely any. Hull was taken, and the army of insurgents, kept under rigid discipline, moved onwards till they reached the river Don.

Their army consisted of 30,000 men, "as tall men, well-horsed and well-appointed, as any men could be;" and they had with them all the nobility and gentry of the North.

At Doncaster they found themselves face to face with Shrewsbury and Norfolk, well chosen agents for

the purpose the Government had in view; for the rebels, claiming to uphold the rights of the old nobility and the old Church, here found themselves opposed by two nobles

of the oldest blood and the strongest Catholic convictions in England. The rebels determined to treat, principally on the recommendation of Aske, who seems to have been

really patriotic, and to have wished to avoid civil war. It was agreed that a conference should be held upon the bridge of Doncaster, and there a petition was intrusted

to Sir Robert Bowes and Sir Ralph Elleskar to carry to the King, Norfolk agreeing to accompany them. Meanwhile, the rebel forces were disbanded.

The King contrived to win over these emissaries to his party, but Aske continued his organizations; and when no satisfactory answer had been given by the close of November,

he recalled his army to his standards, and again advanced to the Don. At Norfolk's earnest intercession the King at last agreed, against his own judgment, to grant a general

pardon, and to call a Parliament, to be held almost immediately, at York. A conference between Norfolk and Aske was held at Doncaster, and Aske on his knees accepted the

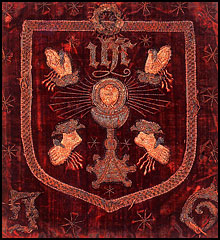

conditions, and threw aside the badge of the five wounds of Christ which had been assumed by the rebels.

It seems certain that the rebels at the time believed that the whole of their petitions had been granted [see 24 Articles]. It is possible

that Norfolk, who had much sympathy with them, held out larger promises than Henry intended. The King's views at all events were not what the rebels supposed. He at once

proceeded to organize the North, to establish fortified posts, and secure the ordnance stores. Norfolk was sent to Pontefract to make preparations for the coming Parliament.

All this looked very unlike a favourable answer to the insurgents' petition. Still more were they disappointed when they found that, instead of a general amnesty, each

individual had to petition for his own pardon, and received it only in exchange for the oath of allegiance.

There was much natural disappointment and smouldering discontent. A man of little influence, called Sir Francis Bigod, contrived a disorderly rising in opposition to the

old chiefs. This afforded opportunity for Norfolk to establish martial law, and seventy-four persons were hanged. Perhaps some new treasonable correspondence was discovered,

and perhaps the opportunity for vengeance had now arrived, but without any very clear renewal of their offences, the three leaders of the old insurrection—Aske,

Darcy, and Constable—were arrested (March). Discontented words could no doubt be proved against them, and on this the charges against

them were chiefly based. They were all condemned and executed, as were also many others of the prominent gentry of the North. Nineteen of the Lincolnshire rebels were executed

(July 1537).

Of the three leaders, by far the most interesting is Aske. His popularity and influence were enormous, his power of organization seems to have been great,

and there is visible in his whole career a genuine desire for the objects of the insurrection, apart from his own aggrandizement, which, coupled with his marked moderation and

uprightness, renders him a very remarkable character.

AJ Notes:

[1. Low-born (i.e., Cromwell, et al.). Villein: 'one of the class of serfs in the feudal system' —OED.]

[2. Cranmer and his fellow reformers.]

Text source:

Bright, J. Franck. English History for the Use of Public Schools.

London: Rivingtons, 1876. 404-8.

Other Local Resources:

Books for further study:

Bernard, G. W. The King's Reformation: Henry VIII And the Remaking of the English Church.

New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 2007.

Bush, Michael. The Pilgrimage of Grace: A Study of the Rebel Armies

of October 1536. Manchester: Manchester University Press, 1996.

Duffy, Eamon. The Stripping of the Altars. 2nd Ed.

New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 2005.

Hoyle, R. W. The Pilgrimage of Grace and the Politics of the 1530s.

Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2005.

Moorehouse, Geoffrey. Pilgrimage of Grace: The Rebellion That Shook

Henry VIII's Throne. London: Phoenix Press, 2003.

The Pilgrimage of Grace on the Web:

| to Henry VIII |

| to Renaissance English Literature |

| to Luminarium Encyclopedia |

Badge of the Five Wounds of Christ from the collection of the Baroness Herries.

Site ©1996-2022 Anniina Jokinen. All rights reserved.

This page was created on April 13, 2007. Last updated October 19, 2022.

|

Index of Encyclopedia Entries:

Medieval Cosmology

Prices of Items in Medieval England

Edward II

Isabella of France, Queen of England

Piers Gaveston

Thomas of Brotherton, E. of Norfolk

Edmund of Woodstock, E. of Kent

Thomas, Earl of Lancaster

Henry of Lancaster, Earl of Lancaster

Henry of Grosmont, Duke of Lancaster

Roger Mortimer, Earl of March

Hugh le Despenser the Younger

Bartholomew, Lord Burghersh, elder

Hundred Years' War (1337-1453)

Edward III

Philippa of Hainault, Queen of England

Edward, Black Prince of Wales

John of Eltham, Earl of Cornwall

The Battle of Crécy, 1346

The Siege of Calais, 1346-7

The Battle of Poitiers, 1356

Lionel of Antwerp, Duke of Clarence

John of Gaunt, Duke of Lancaster

Edmund of Langley, Duke of York

Thomas of Woodstock, Gloucester

Richard of York, E. of Cambridge

Richard Fitzalan, 3. Earl of Arundel

Roger Mortimer, 2nd Earl of March

The Good Parliament, 1376

Richard II

The Peasants' Revolt, 1381

Lords Appellant, 1388

Richard Fitzalan, 4. Earl of Arundel

Archbishop Thomas Arundel

Thomas de Beauchamp, E. Warwick

Robert de Vere, Earl of Oxford

Ralph Neville, E. of Westmorland

Thomas Mowbray, Duke of Norfolk

Edmund Mortimer, 3. Earl of March

Roger Mortimer, 4. Earl of March

John Holland, Duke of Exeter

Michael de la Pole, E. Suffolk

Hugh de Stafford, 2. E. Stafford

Henry IV

Edward, Duke of York

Edmund Mortimer, 5. Earl of March

Henry Percy, Earl of Northumberland

Sir Henry Percy, "Harry Hotspur"

Thomas Percy, Earl of Worcester

Owen Glendower

The Battle of Shrewsbury, 1403

Archbishop Richard Scrope

Thomas Mowbray, 3. E. Nottingham

John Mowbray, 2. Duke of Norfolk

Thomas Fitzalan, 5. Earl of Arundel

Henry V

Thomas, Duke of Clarence

John, Duke of Bedford

Humphrey, Duke of Gloucester

John Talbot, Earl of Shrewsbury

Richard, Earl of Cambridge

Henry, Baron Scrope of Masham

William de la Pole, Duke of Suffolk

Thomas Montacute, E. Salisbury

Richard Beauchamp, E. of Warwick

Henry Beauchamp, Duke of Warwick

Thomas Beaufort, Duke of Exeter

Cardinal Henry Beaufort

John Beaufort, Earl of Somerset

Sir John Fastolf

John Holland, 2. Duke of Exeter

Archbishop John Stafford

Archbishop John Kemp

Catherine of Valois

Owen Tudor

John Fitzalan, 7. Earl of Arundel

John, Lord Tiptoft

Charles VII, King of France

Joan of Arc

Louis XI, King of France

Charles the Bold, Duke of Burgundy

The Battle of Agincourt, 1415

The Battle of Castillon, 1453

The Wars of the Roses 1455-1485

Causes of the Wars of the Roses

The House of Lancaster

The House of York

The House of Beaufort

The House of Neville

The First Battle of St. Albans, 1455

The Battle of Blore Heath, 1459

The Rout of Ludford, 1459

The Battle of Northampton, 1460

The Battle of Wakefield, 1460

The Battle of Mortimer's Cross, 1461

The 2nd Battle of St. Albans, 1461

The Battle of Towton, 1461

The Battle of Hedgeley Moor, 1464

The Battle of Hexham, 1464

The Battle of Edgecote, 1469

The Battle of Losecoat Field, 1470

The Battle of Barnet, 1471

The Battle of Tewkesbury, 1471

The Treaty of Pecquigny, 1475

The Battle of Bosworth Field, 1485

The Battle of Stoke Field, 1487

Henry VI

Margaret of Anjou

Richard Plantagenet, Duke of York

Edward IV

Elizabeth Woodville

Richard Woodville, 1. Earl Rivers

Anthony Woodville, 2. Earl Rivers

Jane Shore

Edward V

Richard III

George, Duke of Clarence

Ralph Neville, 2. Earl of Westmorland

Richard Neville, Earl of Salisbury

Richard Neville, Earl of Warwick

Edward Neville, Baron Bergavenny

William Neville, Lord Fauconberg

Robert Neville, Bishop of Salisbury

John Neville, Marquis of Montagu

George Neville, Archbishop of York

John Beaufort, 1. Duke Somerset

Edmund Beaufort, 2. Duke Somerset

Henry Beaufort, 3. Duke of Somerset

Edmund Beaufort, 4. Duke Somerset

Margaret Beaufort

Edmund Tudor, Earl of Richmond

Jasper Tudor, Earl of Pembroke

Humphrey Stafford, D. Buckingham

Henry Stafford, Duke of Buckingham

Humphrey Stafford, E. of Devon

Thomas, Lord Stanley, Earl of Derby

Sir William Stanley

Archbishop Thomas Bourchier

Henry Bourchier, Earl of Essex

John Mowbray, 3. Duke of Norfolk

John Mowbray, 4. Duke of Norfolk

John Howard, Duke of Norfolk

Henry Percy, 2. E. Northumberland

Henry Percy, 3. E. Northumberland

Henry Percy, 4. E. Northumberland

William, Lord Hastings

Henry Holland, Duke of Exeter

William Fitzalan, Earl of Arundel

William Herbert, 1. Earl of Pembroke

John de Vere, 12th Earl of Oxford

John de Vere, 13th Earl of Oxford

Thomas de Clifford, 8. Baron Clifford

John de Clifford, 9. Baron Clifford

John Tiptoft, Earl of Worcester

Thomas Grey, 1. Marquis Dorset

Sir Andrew Trollop

Archbishop John Morton

Edward Plantagenet, E. of Warwick

John Talbot, 2. E. Shrewsbury

John Talbot, 3. E. Shrewsbury

John de la Pole, 2. Duke of Suffolk

John de la Pole, E. of Lincoln

Edmund de la Pole, E. of Suffolk

Richard de la Pole

John Sutton, Baron Dudley

James Butler, 5. Earl of Ormonde

Sir James Tyrell

Edmund Grey, first Earl of Kent

George Grey, 2nd Earl of Kent

John, 5th Baron Scrope of Bolton

James Touchet, 7th Baron Audley

Walter Blount, Lord Mountjoy

Robert Hungerford, Lord Moleyns

Thomas, Lord Scales

John, Lord Lovel and Holand

Francis Lovell, Viscount Lovell

Sir Richard Ratcliffe

William Catesby

Ralph, 4th Lord Cromwell

Jack Cade's Rebellion, 1450

Tudor Period

King Henry VII

Queen Elizabeth of York

Arthur, Prince of Wales

Lambert Simnel

Perkin Warbeck

The Battle of Blackheath, 1497

King Ferdinand II of Aragon

Queen Isabella of Castile

Maximilian I, Holy Roman Emperor

King Henry VIII

Queen Catherine of Aragon

Queen Anne Boleyn

Queen Jane Seymour

Queen Anne of Cleves

Queen Catherine Howard

Queen Katherine Parr

King Edward VI

Queen Mary I

Queen Elizabeth I

Henry Fitzroy, Duke of Richmond

Margaret Tudor, Queen of Scotland

James IV, King of Scotland

The Battle of Flodden Field, 1513

James V, King of Scotland

Mary of Guise, Queen of Scotland

Mary Tudor, Queen of France

Louis XII, King of France

Francis I, King of France

The Battle of the Spurs, 1513

Field of the Cloth of Gold, 1520

Charles V, Holy Roman Emperor

Eustace Chapuys, Imperial Ambassador

The Siege of Boulogne, 1544

Cardinal Thomas Wolsey

Archbishop Thomas Cranmer

Thomas Cromwell, Earl of Essex

Thomas, Lord Audley

Thomas Wriothesley, E. Southampton

Sir Richard Rich

Edward Stafford, D. of Buckingham

Thomas Howard, 2nd Duke of Norfolk

Thomas Howard, 3rd Duke of Norfolk

John Dudley, Duke of Northumberland

Charles Brandon, Duke of Suffolk

Thomas Boleyn, Earl of Wiltshire

George Boleyn, Viscount Rochford

John Russell, Earl of Bedford

Thomas Grey, 2. Marquis of Dorset

Henry Grey, D. of Suffolk

Charles Somerset, Earl of Worcester

George Talbot, 4. E. Shrewsbury

Francis Talbot, 5. E. Shrewsbury

Henry Algernon Percy,

5th Earl of Northumberland

Henry Algernon Percy,

6th Earl of Northumberland

Ralph Neville, 4. E. Westmorland

Henry Neville, 5. E. Westmorland

William Paulet, Marquis of Winchester

Sir Francis Bryan

Sir Nicholas Carew

John de Vere, 15th Earl of Oxford

John de Vere, 16th Earl of Oxford

Thomas Seymour, Lord Admiral

Edward Seymour, Protector Somerset

Margaret Pole, Countess of Salisbury

Henry Pole, Lord Montague

Sir Geoffrey Pole

Thomas Manners, Earl of Rutland

Henry Manners, Earl of Rutland

Henry Bourchier, 2. Earl of Essex

Robert Radcliffe, 1. Earl of Sussex

Henry Radcliffe, 2. Earl of Sussex

George Hastings, Earl of Huntingdon

Henry Courtenay, Marquis of Exeter

George Neville, Baron Bergavenny

Sir Edward Neville

William, Lord Paget

William Sandys, Baron Sandys

William Fitzwilliam, E. Southampton

Sir Anthony Browne

Sir Thomas Wriothesley

Sir William Kingston

George Brooke, Lord Cobham

Sir Richard Southwell

Thomas Fiennes, 9th Lord Dacre

Sir Francis Weston

Henry Norris

Lady Jane Grey

Sir Thomas Arundel

Sir Richard Sackville

Sir William Petre

Sir John Cheke

Walter Haddon, L.L.D

Sir Peter Carew

Sir John Mason

Nicholas Wotton

John Taylor

Sir Thomas Wyatt, the Younger

Cardinal Lorenzo Campeggio

Cardinal Reginald Pole

Stephen Gardiner, Bishop of Winchester

Edmund Bonner, Bishop of London

Nicholas Ridley, Bishop of London

John Hooper, Bishop of Gloucester

John Aylmer, Bishop of London

Thomas Linacre

William Grocyn

Archbishop William Warham

Cuthbert Tunstall, Bishop of Durham

Richard Fox, Bishop of Winchester

Edward Fox, Bishop of Hereford

Pope Julius II

Pope Leo X

Pope Clement VII

Pope Paul III

Pope Pius V

Pico della Mirandola

Desiderius Erasmus

Martin Bucer

Richard Pace

Christopher Saint-German

Thomas Tallis

Elizabeth Barton, the Nun of Kent

Hans Holbein, the Younger

The Sweating Sickness

Dissolution of the Monasteries

Pilgrimage of Grace, 1536

Robert Aske

Anne Askew

Lord Thomas Darcy

Sir Robert Constable

Oath of Supremacy

The Act of Supremacy, 1534

The First Act of Succession, 1534

The Third Act of Succession, 1544

The Ten Articles, 1536

The Six Articles, 1539

The Second Statute of Repeal, 1555

The Act of Supremacy, 1559

Articles Touching Preachers, 1583

Queen Elizabeth I

William Cecil, Lord Burghley

Robert Cecil, 1st Earl of Salisbury

Sir Francis Walsingham

Sir Nicholas Bacon

Sir Thomas Bromley

Robert Dudley, Earl of Leicester

Ambrose Dudley, Earl of Warwick

Henry Carey, Lord Hunsdon

Sir Thomas Egerton, Viscount Brackley

Sir Francis Knollys

Katherine "Kat" Ashley

Lettice Knollys, Countess of Leicester

George Talbot, 6. E. of Shrewsbury

Elizabeth, Countess of Shrewsbury

Gilbert Talbot, 7. E. of Shrewsbury

Sir Henry Sidney

Sir Robert Sidney

Archbishop Matthew Parker

Walter Devereux, 1st Earl of Essex

Robert Devereux, 2nd Earl of Essex

Penelope Devereux, Lady Rich

Sir Christopher Hatton

Edward Courtenay, E. Devonshire

Edward Manners, 3rd Earl of Rutland

Thomas Radcliffe, 3. Earl of Sussex

Henry Radcliffe, 4. Earl of Sussex

Robert Radcliffe, 5. Earl of Sussex

William Parr, Marquis of Northampton

Henry Wriothesley, 2. Southampton

Henry Wriothesley, 3. Southampton

Charles Neville, 6. E. Westmorland

Thomas Percy, 7. E. Northumberland

Henry Percy, 8. E. Northumberland

Henry Percy, 9. E. Nothumberland

William Herbert, 1. Earl of Pembroke

Charles, Lord Howard of Effingham

Thomas Howard, 4th Duke of Norfolk

Henry Howard, 1. Earl of Northampton

Thomas Howard, 1. Earl of Suffolk

Henry Hastings, 3. E. of Huntingdon

Edward Manners, 3rd Earl of Rutland

Roger Manners, 5th Earl of Rutland

Francis Manners, 6th Earl of Rutland

Henry FitzAlan, 12. Earl of Arundel

Thomas, Earl Arundell of Wardour

Edward Somerset, E. of Worcester

William Davison

Sir Walter Mildmay

Sir Ralph Sadler

Sir Amyas Paulet

Gilbert Gifford

Anthony Browne, Viscount Montague

François, Duke of Alençon & Anjou

Mary, Queen of Scots

Henry Stuart, Lord Darnley

James Hepburn, Earl of Bothwell

Anthony Babington and the Babington Plot

John Knox

Philip II of Spain

The Spanish Armada, 1588

Sir Francis Drake

Sir John Hawkins

William Camden

Archbishop Whitgift

Martin Marprelate Controversy

John Penry (Martin Marprelate)

Richard Bancroft, Archbishop of Canterbury

John Dee, Alchemist

Philip Henslowe

Edward Alleyn

The Blackfriars Theatre

The Fortune Theatre

The Rose Theatre

The Swan Theatre

Children's Companies

The Admiral's Men

The Lord Chamberlain's Men

Citizen Comedy

The Isle of Dogs, 1597

Common Law

Court of Common Pleas

Court of King's Bench

Court of Star Chamber

Council of the North

Fleet Prison

Assize

Attainder

First Fruits & Tenths

Livery and Maintenance

Oyer and terminer

Praemunire

The Stuarts

King James I of England

Anne of Denmark

Henry, Prince of Wales

The Gunpowder Plot, 1605

George Villiers, 1st Duke of Buckingham

Robert Carr, Earl of Somerset

Arabella Stuart, Lady Lennox

William Alabaster

Bishop Hall

Bishop Thomas Morton

Archbishop William Laud

John Selden

Lucy Harington, Countess of Bedford

Henry Lawes

King Charles I

Queen Henrietta Maria

Long Parliament

Rump Parliament

Kentish Petition, 1642

Thomas Wentworth, Earl of Strafford

John Digby, Earl of Bristol

George Digby, 2nd Earl of Bristol

Thomas Fairfax, 3rd Lord Fairfax

Robert Devereux, 3rd E. of Essex

Robert Sidney, 2. E. of Leicester

Algernon Percy, E. of Northumberland

Henry Montagu, Earl of Manchester

Edward Montagu, 2. Earl of Manchester

The Restoration

King Charles II

King James II

Test Acts

Greenwich Palace

Hatfield House

Richmond Palace

Windsor Palace

Woodstock Manor

The Cinque Ports

Mermaid Tavern

Malmsey Wine

Great Fire of London, 1666

Merchant Taylors' School

Westminster School

The Sanctuary at Westminster

"Sanctuary"

Images:

Chart of the English Succession from William I through Henry VII

Medieval English Drama

London c1480, MS Royal 16

London, 1510, the earliest view in print

Map of England from Saxton's Descriptio Angliae, 1579

London in late 16th century

Location Map of Elizabethan London

Plan of the Bankside, Southwark, in Shakespeare's time

Detail of Norden's Map of the Bankside, 1593

Bull and Bear Baiting Rings from the Agas Map (1569-1590, pub. 1631)

Sketch of the Swan Theatre, c. 1596

Westminster in the Seventeenth Century, by Hollar

Visscher's View of London, 1616

Larger Visscher's View in Sections

c. 1690. View of London Churches, after the Great Fire

The Yard of the Tabard Inn from Thornbury, Old and New London

|

|