|

|

|

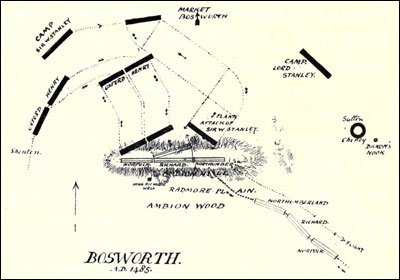

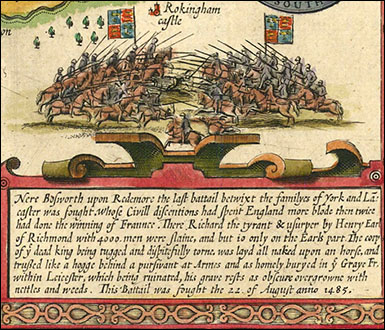

THE BATTLE OF BOSWORTH FIELD (Aug. 22, 1485), was fought between Richard III and Henry, Earl of Richmond, afterwards Henry VII.

On August [7], Henry landed at Milford Haven and passed on without opposition to Shrewsbury, being joined by a large number of Welshmen. He then marched on to Tamworth, where he arrived on the 18th.

On the 20th he was at Atherstone, where he was met by Lord Stanley and by Sir William Stanley, who both promised to desert Richard during

the battle. Meanwhile Richard, having mustered his forces at Nottingham, marched to Leicester and encamped at Bosworth on the 21st.

On the next morning the two armies met between Bosworth and Atherstone at a place known as Whitemoors, near the village of Sutton Cheneys. The battle was mainly a hand-to-hand encounter, the Stanleys

for some time keeping aloof from the fight till, at a critical moment, they joined Richmond. Richard, perceiving that he was betrayed, and crying out, "Treason, treason!" endeavoured only to sell his

life as dearly as possible, and refused to leave the field till, overpowered by numbers, he fell dead in the midst of his enemies. The crown was picked up on the field of battle and placed by Sir William

Stanley on the head of Richmond, who was at once saluted king by the whole army.

Among those that perished on Richard's side were the Duke of Norfolk, Lord Ferrers, Sir Richard Ratcliffe, and Sir Robert Brackenbury,

while the only person of note in Henry's army who was slain was his standard-bearer, Sir William Brandon, who is said to have been killed by Richard himself.

The Dictionary of English History. Sidney J. Low and F. S. Pulling, eds.

London: Cassell and Company, Ltd., 1910. 198.

THE BATTLE OF BOSWORTH

By C. Oman

At last on August 1 Henry of Richmond set sail from Harfleur; the Regent Anne of France had lent him 60,000 francs, and collected for him 1,800 mercenaries

and a small fleet. The adventurer was accompanied by his uncle, Jasper Tudor, the Earl of Oxford, Sir Edward Woodville, Sir John Welles,

heir of the attainted barony of Welles, Sir Edward Courtenay, who claimed the earldom of Devon, his kinsman the Bishop of Exeter [Peter Courtenay], Morton, Bishop of Ely,

and some scores of exiled knights and squires, among whom Yorkists were almost as numerous as Lancastrians. The French auxiliaries were under a Savoyard captain named Philibert de Chaundé.

The Marquis of Dorset and Sir John Bourchier had been left at Paris in pledge for the loan made by the French government. Richmond did not desire to have the marquis

with him, for he had been detected in correspondence with his mother the queen-dowager, who urged him to abandon conspiracy and submit to King Richard.

Stealing down the Breton coast, so as to avoid the English fleet, Richmond turned northward when he had passed the longitude of Lands End, and came ashore in Milford Haven on August 7. He had selected

this remote region as his landing point both because he knew that he was expected to strike at the English south coast, and because he had assurance of help from many old retainers of his uncle the

Earl of Pembroke. He was himself a Welshman and could make a good appeal to the local patriotism of his countrymen. On landing he raised not only the royal banner of

England but the ancient standard of Cadwallader, a red dragon upon a field of white and green, the beast which was afterwards used as the device of the house of Tudor, and the sinister supporter

of their coat-of-arms.

Stealing down the Breton coast, so as to avoid the English fleet, Richmond turned northward when he had passed the longitude of Lands End, and came ashore in Milford Haven on August 7. He had selected

this remote region as his landing point both because he knew that he was expected to strike at the English south coast, and because he had assurance of help from many old retainers of his uncle the

Earl of Pembroke. He was himself a Welshman and could make a good appeal to the local patriotism of his countrymen. On landing he raised not only the royal banner of

England but the ancient standard of Cadwallader, a red dragon upon a field of white and green, the beast which was afterwards used as the device of the house of Tudor, and the sinister supporter

of their coat-of-arms.

For a few days Henry received but trifling reinforcements, but he struck into the Cardiganshire mountains, a district where, if his adherents were slow to join him, he might hope to maintain an irregular

warfare in the style of Owen Glendower. After a short delay the Welsh gentry began to come in to his aid; the wealthiest and most warlike chief Rhys ap Thomas consented to put

himself at their head, after he had been promised the justiciarship of South Wales. Sir Walter Herbert had charge of the district in King Richard's name, but the levies that he called out melted away to

the invader's camp, and he himself was suspected of half-heartedness.

Richmond met no resistance as he conducted his ever-growing host across Cardiganshire toward the upper Severn. By way of Newtown and Welshpool he came down on Shrewsbury, which opened its gates on

August 15 after one day's parleying; this was a good omen, for hitherto the earl had received no help save from the Welsh. On the next day but one Sir Gilbert Talbot, uncle and guardian of the

young Earl of Shrewsbury, joined him with 500 of the retainers of his old Lancastrian house.

From this moment onward English malcontents with small bodies of recruits kept pouring into Richmond's camp, but though he advanced boldly into the midlands, making directly towards Richard's post at

Nottingham, his whole force was still small; he had not more than 5,000 men at the decisive battle that gave him the crown. His confidence was due to the fact that he had secret promises of aid from

all sides; the Stanleys had let him pass Shrewsbury unmolested, and had sent him word that they would place the forces of Cheshire and Lancashire at his disposition when they had got Lord Strange

[son of Thomas, Lord Stanley] out of the king's hands. Many other magnates had already given similar assurances.

Meanwhile Richard had received the news of the invader's landing somewhat later than he had expected, owing to the remoteness of Milford Haven. When he learnt that Richmond

was marching straight towards him, he ordered out all the shire levies which had been so long ready, and summoned in his most trustworthy adherents in the baronage. Norfolk,

Northumberland, and some twenty more of the peers rallied to his standard at Leicester within a few days,1 but the lords of the extreme south and west were still

absent when the crisis came.

Lord Stanley, who had been summoned with the rest, sent a futile excuse, yet raised all Cheshire and Lancashire under his own banner and advanced as far as Lichfield. His son

Strange made an attempt to escape from custody and join him, whereupon Richard put him in irons, and sent word to his father that if he turned traitor his son should be beheaded without a moment's delay.

This did not prevent Sir William Stanley, who commanded a part of the Cheshire levies, from visiting Richmond's camp at Stafford, and pledging himself to join him on the

battlefield; but the head of the house hung back as long as possible, to save the life of his heir.

On August 20 the earl's army advanced from Tamworth to Atherstone, while the king had gathered his forces at Leicester. On the 21st the one moved forward from Atherstone to the White Moor, a few miles

south-west from Bosworth, while the other marched out from Leicester to Sutton Cheney; only two miles divided their camps, and it was obvious that a decisive engagement must take place next day. The host

of the Stanleys, with Sir William leading its vaward, and Lord Stanley keeping discreetly to the rear, was near Bosworth that same evening,

equidistant from the two hostile armies. Both the king and Richmond were aware of its approach, and neither was pleased, for Richard apprehended treason, and his rival had hoped to be openly joined by

these cautious allies before the battle began.

The king was well aware that the spirit of his troops was unsatisfactory; his confidential advisers had warned him that treachery was on foot; and unless he could bear down the enemy by his first onset,

his superior numbers—he had two men to Richmond's one—were not likely to avail him much. But he trusted to his own energy and military skill, and hoped to conquer despite the lukewarmness of

the majority of his followers. Nevertheless he had dismal forebodings; his rest was broken by horrible dreams, and he showed next morning a face not only haggard, but disfigured with a death-like pallor.2

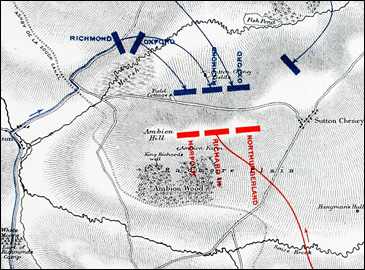

But his courage was unbroken, and he promised victory to his doubting captains in words of haughty confidence. His position was excellent; the army was drawn out in the usual three divisions on the slopes

of Ambion Hill, a well-marked rising ground two miles south of Bosworth. It was partly divided from the enemy by marshy fields formed by the little river Sence. The king led the main battle, the

Duke of Norfolk the vaward or right wing, the Earl of Northumberland the rear.

His adversaries, on the other side of the marsh, had formed their smaller host in two divisions only; the Earl of Oxford led the vaward, while the main battle was under Richmond's

own command. Contrary to what might have been expected, they took the offensive, reckoning, no doubt, on treachery in the king's ranks. They moved off eastward, Oxford's corps leading, till they had circumvented

the marshy ground, and faced the royalists with the sun at their backs and the wind also behind them—advantages of no mean importance in the archery-fight which always opened an English engagement.

When they had cleared the boggy tract, and began to advance up the slopes of Ambion Hill, with their western flank still covered by the impassable marsh, the king first opened upon them with his artillery,

and then charged down upon them. Norfolk's corps came into collision with that of Oxford, while Richard attacked the earl's

main body. Northumberland, on the other wing of the royal host, deliberately held back and would not get into action. Before ordering the line to advance, the king had sent orders

to Lord Stanley to draw in to his banner, and, when he made no movement issued a command for the instant execution of his son Strange. But those charged with the matter wisely deferred

obedience till the battle should be over, and the young man escaped with his life.

When the two armies came into close contact it was at once evident that many of the king's men were not inclined to fight. They hung back, kept up a feeble archery fire from a distance, and refused to close.

Oxford, who had halted to receive the attack, bade his banner go forward again, and began to mount the slopes. On this more serious fighting began, for Norfolk

with his son Surrey, and some others of the king's adherents, tried to do their duty, and fell hotly upon the earl's front.

At the same moment Richard himself, having marked the position of Richmond in the hostile line, charged at the head of his bodyguard, broke into the Lancastrian

main body and seemed for a moment likely to prevail. He slew with his own hand, as it is said, Sir William Brandon, Richmond's standard-bearer, and encountered the earl hand to hand for a short space. But by this

moment the battle was lost, for Sir William Stanley, who had been drawing nearer ever since the fighting began, now fell upon Richard's host in flank and rear. With a cry of treason

the royalist main body broke up and fled. The Stanleys took up the pursuit, which passed away to the east with no great slaughter, for the pursuers understood that the vanquished had no heart in the struggle and had

deliberately given them the victory.

King Richard, however, refused to fly, though faithful friends brought him his horse, and bade him escape while they held back the enemy for a moment. The usurper replied that at least

he would die King of England, and plunged back into the fight. A moment later, shouting "Treason! treason!" as he laid about him with his battle-axe, he was ringed round by many foes and hewn down; his helmet was

battered through and his brains beaten out.

It was the end of a brave man, and his courage touched the heart even of those who remembered his crimes. The finest stanzas written in fifteenth century England were given to his memory by an admiring enemy, a

retainer of the Stanleys, who wrote the Ballad of Lady Bessie:—

Then a knight to King Richard gan say—good Sir William Harrington—

He saith "all wee are like this day to the death soone to be done;

There may no man their strokes abide, the Stanleys' dints they be so stronge.

Yee may come back at another tide, methinks yee tarry here too longe.

Your horsse at your hand is ready, another day you may worshipp win

And come to raigne with royaltye, and weare your crown and be our king".

"Nay, give me my battle-axe in my hand, sett the crowne of England on my head so high,

For by Him that made both sea and land, King of England this day I will dye.

One foot I will never flee whilst the breath is my brest within."

As he said so did it be—if hee lost his life he died a king.3

|

The battered crown which had fallen from Richard's helmet was found in a hawthorn bush, where it had probably been hidden by a plunderer, and set on the head of Richmond by

Lord Stanley, while all the victorious army hailed the earl by his new title of Henry VII.

The battered crown which had fallen from Richard's helmet was found in a hawthorn bush, where it had probably been hidden by a plunderer, and set on the head of Richmond by

Lord Stanley, while all the victorious army hailed the earl by his new title of Henry VII.

Along with the king there fell his chief supporter, John Duke of Norfolk; the Lord Ferrers of Chartley, Sir Richard Ratcliffe, his well-known councillor,

Sir Robert Brakenbury, lieutenant of the Tower of London, Sir Robert Percy, controller of the royal household, Sir William Conyers, and about 1,000 others, as was reported, probably with some exaggeration, for the

battle had not been hot nor the pursuit merciless.

The victors lost not above 100 men, of whom the only personage of note was the standard-bearer Sir William Brandon. The Earl of Surrey was taken prisoner, grievously wounded, and lodged

in prison. Catesby was captured in the flight, and executed along with two yeomen of the king's chamber—a father and son named Breacher. These were the only lives taken in cold blood by

Henry of Richmond.

The corpse of Richard was stripped and carried to Leicester across the back of a horse in unseemly fashion, with head and arms hanging down. It was exposed to the public view for two days, and then decently buried

in the church of the Greyfriars. His monument was destroyed and his bones scattered at the dissolution of the monasteries.

1. If the Ballad of Bosworth Feilde can be trusted, there were with the king the following peers: Norfolk, Kent, Surrey, Lincoln, Northumberland, Westmorland [Ralph Neville, 3rd Earl], Zouch [John la Zouche, 7th Baron], Maltravers [Thomas Fitzalan, 7th Baron], Arundel, Grey of Codnor [Henry Grey, 7th Baron], Audley [James Touchet, 6th Baron], Berkeley [William, 1st Viscount Berkeley], Ferrers of Chartley [Walter Devereux, 7th Baron] and Ferrers of Groby [John Bourchier, 6th Baron], Fitzhugh [Richard, 6th Baron], Dacre [Thomas, 2nd Baron Dacre of Gillesland], Scrope of Bolton [John, 5th Baron], Scrope of Upsal [Ralph, 9th Baron], Lumley [George, 3rd Baron], and Greystock [Ralph de Greystoke, 5th Baron Greystoke]. Lovel seems to have been still with the fleet in the Channel. The list cannot be trusted for all the names.

2. Continuator of the Croyland Chronicle, Fulman, 1684, p. 374.

3. I have corrected some obvious verbal errors in Lady Bessie mainly from the parallel passage—nearly the same in wording—in Bosworth Feilde. See Percy Folio MS., iii., 257 and 362.

Oman, C. The History of England.

London: Longmans, Green, and Co., 1906. 491-6.

Other Local Resources:

Books for further study:

Bennett, Michael. The Battle of Bosworth.

Stroud, Gloucestershire: Sutton Publishing, 2000.

Chrimes, S. B. Henry VII.

New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 1999.

Gravett, Christopher. Bosworth 1485: Last Charge of the Plantagenets.

Oxford: Osprey Publishing, 1999.

Hallam, E., ed. Wars of the Roses: From Richard II to the Fall of Richard III

at Bosworth Field—Seen Through the Eyes of Their Contemporaries.

Grove Press, 1988.

Hammond, Peter. Richard III and the Bosworth Campaign.

Barnsley, Yorkshire: Pen and Sword, 2011.

Hicks, Michael. The Wars of the Roses 1455-1485.

New York: Routledge, 2003.

Ingram, Mike. Battle Story: Bosworth, 1485.

The History Press, 2012.

Ingram, Mike. Richard III and the Battle of Bosworth.

Helion and Company, 2019.

Jones, Michael. Bosworth 1485.

Pegasus Books, 2016.

More, Sir Thomas. History of King Richard III.

Hesperus Press, 2005.

Ross, Charles. Richard III.

New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 2011.

Rowse, A. L. Bosworth Field & the Wars of the Roses.

Wordsworth Military Library; New Ed., 1999.

Shakespeare, William. Richard III.

Folger Shakespeare Library, 2004.

Weir, Alison. The Wars of the Roses.

New York: Ballantine Books, 1996.

The Battle of Bosworth Field on the Web:

| to Richard III |

| to Henry VII |

| to Wars of the Roses

|

| to Luminarium Encyclopedia |

Site ©1996-2022 Anniina Jokinen. All rights reserved.

This page was created on April 12, 2007. Last updated August 22, 2022.

|

Index of Encyclopedia Entries:

Medieval Cosmology

Prices of Items in Medieval England

Edward II

Isabella of France, Queen of England

Piers Gaveston

Thomas of Brotherton, E. of Norfolk

Edmund of Woodstock, E. of Kent

Thomas, Earl of Lancaster

Henry of Lancaster, Earl of Lancaster

Henry of Grosmont, Duke of Lancaster

Roger Mortimer, Earl of March

Hugh le Despenser the Younger

Bartholomew, Lord Burghersh, elder

Hundred Years' War (1337-1453)

Edward III

Philippa of Hainault, Queen of England

Edward, Black Prince of Wales

John of Eltham, Earl of Cornwall

The Battle of Crécy, 1346

The Siege of Calais, 1346-7

The Battle of Poitiers, 1356

Lionel of Antwerp, Duke of Clarence

John of Gaunt, Duke of Lancaster

Edmund of Langley, Duke of York

Thomas of Woodstock, Gloucester

Richard of York, E. of Cambridge

Richard Fitzalan, 3. Earl of Arundel

Roger Mortimer, 2nd Earl of March

The Good Parliament, 1376

Richard II

The Peasants' Revolt, 1381

Lords Appellant, 1388

Richard Fitzalan, 4. Earl of Arundel

Archbishop Thomas Arundel

Thomas de Beauchamp, E. Warwick

Robert de Vere, Earl of Oxford

Ralph Neville, E. of Westmorland

Thomas Mowbray, Duke of Norfolk

Edmund Mortimer, 3. Earl of March

Roger Mortimer, 4. Earl of March

John Holland, Duke of Exeter

Michael de la Pole, E. Suffolk

Hugh de Stafford, 2. E. Stafford

Henry IV

Edward, Duke of York

Edmund Mortimer, 5. Earl of March

Henry Percy, Earl of Northumberland

Sir Henry Percy, "Harry Hotspur"

Thomas Percy, Earl of Worcester

Owen Glendower

The Battle of Shrewsbury, 1403

Archbishop Richard Scrope

Thomas Mowbray, 3. E. Nottingham

John Mowbray, 2. Duke of Norfolk

Thomas Fitzalan, 5. Earl of Arundel

Henry V

Thomas, Duke of Clarence

John, Duke of Bedford

Humphrey, Duke of Gloucester

John Talbot, Earl of Shrewsbury

Richard, Earl of Cambridge

Henry, Baron Scrope of Masham

William de la Pole, Duke of Suffolk

Thomas Montacute, E. Salisbury

Richard Beauchamp, E. of Warwick

Henry Beauchamp, Duke of Warwick

Thomas Beaufort, Duke of Exeter

Cardinal Henry Beaufort

John Beaufort, Earl of Somerset

Sir John Fastolf

John Holland, 2. Duke of Exeter

Archbishop John Stafford

Archbishop John Kemp

Catherine of Valois

Owen Tudor

John Fitzalan, 7. Earl of Arundel

John, Lord Tiptoft

Charles VII, King of France

Joan of Arc

Louis XI, King of France

Charles the Bold, Duke of Burgundy

The Battle of Agincourt, 1415

The Battle of Castillon, 1453

The Wars of the Roses 1455-1485

Causes of the Wars of the Roses

The House of Lancaster

The House of York

The House of Beaufort

The House of Neville

The First Battle of St. Albans, 1455

The Battle of Blore Heath, 1459

The Rout of Ludford, 1459

The Battle of Northampton, 1460

The Battle of Wakefield, 1460

The Battle of Mortimer's Cross, 1461

The 2nd Battle of St. Albans, 1461

The Battle of Towton, 1461

The Battle of Hedgeley Moor, 1464

The Battle of Hexham, 1464

The Battle of Edgecote, 1469

The Battle of Losecoat Field, 1470

The Battle of Barnet, 1471

The Battle of Tewkesbury, 1471

The Treaty of Pecquigny, 1475

The Battle of Bosworth Field, 1485

The Battle of Stoke Field, 1487

Henry VI

Margaret of Anjou

Richard Plantagenet, Duke of York

Edward IV

Elizabeth Woodville

Richard Woodville, 1. Earl Rivers

Anthony Woodville, 2. Earl Rivers

Jane Shore

Edward V

Richard III

George, Duke of Clarence

Ralph Neville, 2. Earl of Westmorland

Richard Neville, Earl of Salisbury

Richard Neville, Earl of Warwick

Edward Neville, Baron Bergavenny

William Neville, Lord Fauconberg

Robert Neville, Bishop of Salisbury

John Neville, Marquis of Montagu

George Neville, Archbishop of York

John Beaufort, 1. Duke Somerset

Edmund Beaufort, 2. Duke Somerset

Henry Beaufort, 3. Duke of Somerset

Edmund Beaufort, 4. Duke Somerset

Margaret Beaufort

Edmund Tudor, Earl of Richmond

Jasper Tudor, Earl of Pembroke

Humphrey Stafford, D. Buckingham

Henry Stafford, Duke of Buckingham

Humphrey Stafford, E. of Devon

Thomas, Lord Stanley, Earl of Derby

Sir William Stanley

Archbishop Thomas Bourchier

Henry Bourchier, Earl of Essex

John Mowbray, 3. Duke of Norfolk

John Mowbray, 4. Duke of Norfolk

John Howard, Duke of Norfolk

Henry Percy, 2. E. Northumberland

Henry Percy, 3. E. Northumberland

Henry Percy, 4. E. Northumberland

William, Lord Hastings

Henry Holland, Duke of Exeter

William Fitzalan, Earl of Arundel

William Herbert, 1. Earl of Pembroke

John de Vere, 12th Earl of Oxford

John de Vere, 13th Earl of Oxford

Thomas de Clifford, 8. Baron Clifford

John de Clifford, 9. Baron Clifford

John Tiptoft, Earl of Worcester

Thomas Grey, 1. Marquis Dorset

Sir Andrew Trollop

Archbishop John Morton

Edward Plantagenet, E. of Warwick

John Talbot, 2. E. Shrewsbury

John Talbot, 3. E. Shrewsbury

John de la Pole, 2. Duke of Suffolk

John de la Pole, E. of Lincoln

Edmund de la Pole, E. of Suffolk

Richard de la Pole

John Sutton, Baron Dudley

James Butler, 5. Earl of Ormonde

Sir James Tyrell

Edmund Grey, first Earl of Kent

George Grey, 2nd Earl of Kent

John, 5th Baron Scrope of Bolton

James Touchet, 7th Baron Audley

Walter Blount, Lord Mountjoy

Robert Hungerford, Lord Moleyns

Thomas, Lord Scales

John, Lord Lovel and Holand

Francis Lovell, Viscount Lovell

Sir Richard Ratcliffe

William Catesby

Ralph, 4th Lord Cromwell

Jack Cade's Rebellion, 1450

Tudor Period

King Henry VII

Queen Elizabeth of York

Arthur, Prince of Wales

Lambert Simnel

Perkin Warbeck

The Battle of Blackheath, 1497

King Ferdinand II of Aragon

Queen Isabella of Castile

Maximilian I, Holy Roman Emperor

King Henry VIII

Queen Catherine of Aragon

Queen Anne Boleyn

Queen Jane Seymour

Queen Anne of Cleves

Queen Catherine Howard

Queen Katherine Parr

King Edward VI

Queen Mary I

Queen Elizabeth I

Henry Fitzroy, Duke of Richmond

Margaret Tudor, Queen of Scotland

James IV, King of Scotland

The Battle of Flodden Field, 1513

James V, King of Scotland

Mary of Guise, Queen of Scotland

Mary Tudor, Queen of France

Louis XII, King of France

Francis I, King of France

The Battle of the Spurs, 1513

Field of the Cloth of Gold, 1520

Charles V, Holy Roman Emperor

Eustace Chapuys, Imperial Ambassador

The Siege of Boulogne, 1544

Cardinal Thomas Wolsey

Archbishop Thomas Cranmer

Thomas Cromwell, Earl of Essex

Thomas, Lord Audley

Thomas Wriothesley, E. Southampton

Sir Richard Rich

Edward Stafford, D. of Buckingham

Thomas Howard, 2nd Duke of Norfolk

Thomas Howard, 3rd Duke of Norfolk

John Dudley, Duke of Northumberland

Charles Brandon, Duke of Suffolk

Thomas Boleyn, Earl of Wiltshire

George Boleyn, Viscount Rochford

John Russell, Earl of Bedford

Thomas Grey, 2. Marquis of Dorset

Henry Grey, D. of Suffolk

Charles Somerset, Earl of Worcester

George Talbot, 4. E. Shrewsbury

Francis Talbot, 5. E. Shrewsbury

Henry Algernon Percy,

5th Earl of Northumberland

Henry Algernon Percy,

6th Earl of Northumberland

Ralph Neville, 4. E. Westmorland

Henry Neville, 5. E. Westmorland

William Paulet, Marquis of Winchester

Sir Francis Bryan

Sir Nicholas Carew

John de Vere, 15th Earl of Oxford

John de Vere, 16th Earl of Oxford

Thomas Seymour, Lord Admiral

Edward Seymour, Protector Somerset

Margaret Pole, Countess of Salisbury

Henry Pole, Lord Montague

Sir Geoffrey Pole

Thomas Manners, Earl of Rutland

Henry Manners, Earl of Rutland

Henry Bourchier, 2. Earl of Essex

Robert Radcliffe, 1. Earl of Sussex

Henry Radcliffe, 2. Earl of Sussex

George Hastings, Earl of Huntingdon

Henry Courtenay, Marquis of Exeter

George Neville, Baron Bergavenny

Sir Edward Neville

William, Lord Paget

William Sandys, Baron Sandys

William Fitzwilliam, E. Southampton

Sir Anthony Browne

Sir Thomas Wriothesley

Sir William Kingston

George Brooke, Lord Cobham

Sir Richard Southwell

Thomas Fiennes, 9th Lord Dacre

Sir Francis Weston

Henry Norris

Lady Jane Grey

Sir Thomas Arundel

Sir Richard Sackville

Sir William Petre

Sir John Cheke

Walter Haddon, L.L.D

Sir Peter Carew

Sir John Mason

Nicholas Wotton

John Taylor

Sir Thomas Wyatt, the Younger

Cardinal Lorenzo Campeggio

Cardinal Reginald Pole

Stephen Gardiner, Bishop of Winchester

Edmund Bonner, Bishop of London

Nicholas Ridley, Bishop of London

John Hooper, Bishop of Gloucester

John Aylmer, Bishop of London

Thomas Linacre

William Grocyn

Archbishop William Warham

Cuthbert Tunstall, Bishop of Durham

Richard Fox, Bishop of Winchester

Edward Fox, Bishop of Hereford

Pope Julius II

Pope Leo X

Pope Clement VII

Pope Paul III

Pope Pius V

Pico della Mirandola

Desiderius Erasmus

Martin Bucer

Richard Pace

Christopher Saint-German

Thomas Tallis

Elizabeth Barton, the Nun of Kent

Hans Holbein, the Younger

The Sweating Sickness

Dissolution of the Monasteries

Pilgrimage of Grace, 1536

Robert Aske

Anne Askew

Lord Thomas Darcy

Sir Robert Constable

Oath of Supremacy

The Act of Supremacy, 1534

The First Act of Succession, 1534

The Third Act of Succession, 1544

The Ten Articles, 1536

The Six Articles, 1539

The Second Statute of Repeal, 1555

The Act of Supremacy, 1559

Articles Touching Preachers, 1583

Queen Elizabeth I

William Cecil, Lord Burghley

Robert Cecil, 1st Earl of Salisbury

Sir Francis Walsingham

Sir Nicholas Bacon

Sir Thomas Bromley

Robert Dudley, Earl of Leicester

Ambrose Dudley, Earl of Warwick

Henry Carey, Lord Hunsdon

Sir Thomas Egerton, Viscount Brackley

Sir Francis Knollys

Katherine "Kat" Ashley

Lettice Knollys, Countess of Leicester

George Talbot, 6. E. of Shrewsbury

Elizabeth, Countess of Shrewsbury

Gilbert Talbot, 7. E. of Shrewsbury

Sir Henry Sidney

Sir Robert Sidney

Archbishop Matthew Parker

Walter Devereux, 1st Earl of Essex

Robert Devereux, 2nd Earl of Essex

Penelope Devereux, Lady Rich

Sir Christopher Hatton

Edward Courtenay, E. Devonshire

Edward Manners, 3rd Earl of Rutland

Thomas Radcliffe, 3. Earl of Sussex

Henry Radcliffe, 4. Earl of Sussex

Robert Radcliffe, 5. Earl of Sussex

William Parr, Marquis of Northampton

Henry Wriothesley, 2. Southampton

Henry Wriothesley, 3. Southampton

Charles Neville, 6. E. Westmorland

Thomas Percy, 7. E. Northumberland

Henry Percy, 8. E. Northumberland

Henry Percy, 9. E. Nothumberland

William Herbert, 1. Earl of Pembroke

Charles, Lord Howard of Effingham

Thomas Howard, 4th Duke of Norfolk

Henry Howard, 1. Earl of Northampton

Thomas Howard, 1. Earl of Suffolk

Henry Hastings, 3. E. of Huntingdon

Edward Manners, 3rd Earl of Rutland

Roger Manners, 5th Earl of Rutland

Francis Manners, 6th Earl of Rutland

Henry FitzAlan, 12. Earl of Arundel

Thomas, Earl Arundell of Wardour

Edward Somerset, E. of Worcester

William Davison

Sir Walter Mildmay

Sir Ralph Sadler

Sir Amyas Paulet

Gilbert Gifford

Anthony Browne, Viscount Montague

François, Duke of Alençon & Anjou

Mary, Queen of Scots

Henry Stuart, Lord Darnley

James Hepburn, Earl of Bothwell

Anthony Babington and the Babington Plot

John Knox

Philip II of Spain

The Spanish Armada, 1588

Sir Francis Drake

Sir John Hawkins

William Camden

Archbishop Whitgift

Martin Marprelate Controversy

John Penry (Martin Marprelate)

Richard Bancroft, Archbishop of Canterbury

John Dee, Alchemist

Philip Henslowe

Edward Alleyn

The Blackfriars Theatre

The Fortune Theatre

The Rose Theatre

The Swan Theatre

Children's Companies

The Admiral's Men

The Lord Chamberlain's Men

Citizen Comedy

The Isle of Dogs, 1597

Common Law

Court of Common Pleas

Court of King's Bench

Court of Star Chamber

Council of the North

Fleet Prison

Assize

Attainder

First Fruits & Tenths

Livery and Maintenance

Oyer and terminer

Praemunire

The Stuarts

King James I of England

Anne of Denmark

Henry, Prince of Wales

The Gunpowder Plot, 1605

George Villiers, 1st Duke of Buckingham

Robert Carr, Earl of Somerset

Arabella Stuart, Lady Lennox

William Alabaster

Bishop Hall

Bishop Thomas Morton

Archbishop William Laud

John Selden

Lucy Harington, Countess of Bedford

Henry Lawes

King Charles I

Queen Henrietta Maria

Long Parliament

Rump Parliament

Kentish Petition, 1642

Thomas Wentworth, Earl of Strafford

John Digby, Earl of Bristol

George Digby, 2nd Earl of Bristol

Thomas Fairfax, 3rd Lord Fairfax

Robert Devereux, 3rd E. of Essex

Robert Sidney, 2. E. of Leicester

Algernon Percy, E. of Northumberland

Henry Montagu, Earl of Manchester

Edward Montagu, 2. Earl of Manchester

The Restoration

King Charles II

King James II

Test Acts

Greenwich Palace

Hatfield House

Richmond Palace

Windsor Palace

Woodstock Manor

The Cinque Ports

Mermaid Tavern

Malmsey Wine

Great Fire of London, 1666

Merchant Taylors' School

Westminster School

The Sanctuary at Westminster

"Sanctuary"

Images:

Chart of the English Succession from William I through Henry VII

Medieval English Drama

London c1480, MS Royal 16

London, 1510, the earliest view in print

Map of England from Saxton's Descriptio Angliae, 1579

London in late 16th century

Location Map of Elizabethan London

Plan of the Bankside, Southwark, in Shakespeare's time

Detail of Norden's Map of the Bankside, 1593

Bull and Bear Baiting Rings from the Agas Map (1569-1590, pub. 1631)

Sketch of the Swan Theatre, c. 1596

Westminster in the Seventeenth Century, by Hollar

Visscher's View of London, 1616

Larger Visscher's View in Sections

c. 1690. View of London Churches, after the Great Fire

The Yard of the Tabard Inn from Thornbury, Old and New London

|

|