|

|

|

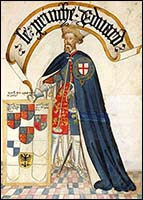

EDWARD, PRINCE OF WALES, called the BLACK PRINCE, and sometimes Edward IV and Edward of Woodstock,

the eldest son of Edward III and Queen Philippa,

was born at Woodstock on 15 June 1330. His father on 16 Sept. allowed five hundred marks a year from the the profits of the county of Chester for his

maintenance, and on 25 Feb. following, the whole of these profits were assigned to the queen for maintaining him and the king's sister Eleanor.1 In the July of that year

the king proposed to marry him to a daughter of Philip VI of France.2

On 18 March 1333 he was invested with the earldom and county of Chester, and in the parliament of 9 Feb. 1337 he was created Duke of Cornwall and received the duchy by charter

dated 17 March. This is the earliest instance of the creation of a duke in England. By the terms of the charter the duchy was to be held by him and the eldest sons of kings of England.3

His tutor was Dr. Walter Burley of Merton College, Oxford. His revenues were placed at the disposal of his mother in March 1334 for the expenses she incurred in bringing up him

and his two sisters, Isabella and Joan.4

Rumours of an impending French invasion led the king in August 1335 to order that he and his household should remove to Nottingham Castle as a place of safety.5 When

two cardinals came to England at the end of 1337 to make peace between the king and Philip, the Duke of Cornwall is said to have met them outside the city of

London, and in company with many nobles to have conducted them to the king.6 On 11 July 1338 his father, who was on the point of leaving England for Flanders,

appointed him guardian of the kingdom during his absence, and he was appointed to the same office on 27 May 1340 and 5 Oct. 1342;7 he was of course too young

to take any nominal part in the administration, which was carried on by the council.

In order to attach John, Duke of Brabant, to his cause, the king in 1339 proposed a marriage between the young Duke of Cornwall and John's daughter Margaret, and

in the spring of 1345 wrote urgently to Pope Clement VI for a dispensation for this marriage.8 On 12 May 1343 Edward created the duke Prince of Wales,

in a parliament held at Westminster, investing him with a circlet, gold ring, and silver rod. The prince accompanied his father to Sluys on 3 July 1345, and Edward

tried to persuade the burgomasters of Ghent, Bruges, and Ypres to accept his son as their lord, but the murder of Van Artevelde put an end to this project.

Both in September and in the following April the prince was called on to furnish troops from his principality and earldom for the impending campaign in France, and as

he incurred heavy debts in the king's service, his father authorised him to make his will, and provided that in case he fell in the war his executors should have all

his revenue for a year.9 He sailed with the king on 11 July, and as soon as he landed at La Hogue received knighthood from his father.10

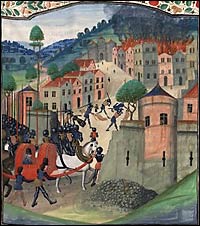

Then he 'made a right good

beginning,' for he rode through the Cotentin, burning and ravaging as he went, and he distinguished himself at the taking of Caen and in the engagement with

the force under Godemar du Faÿ, which endeavoured to prevent the English army from crossing the Somme by the ford of Blanquetaque. Early on Saturday,

26 Aug. [1346], he received the sacrament with his father at Crécy, and took command of the right, or van, of the army with the

Earls of Warwick [Thomas Beauchamp, 11th Earl] and Oxford, Geoffrey Harcourt, Chandos, and other leaders, and

at the head, it is said,

though the numbers are by no means trustworthy, of eight hundred men-at-arms, two thousand archers, and a thousand Welsh foot.

When the Genoese bowmen were discomfited and the front line of the French was in some disorder, the prince appears to have quitted his position in order to

fall on their second line. At this moment, however, the Count of Alençon charged his division with such fury that he was much in peril, and the leaders

who commanded with him sent a messenger to tell his father that he was in great straits, and to beg for succour. When Edward learned that his son was unwounded,

he bade the messenger go back and say that he would send no help, for he would that the lad should win his spurs (the prince was, however, already a knight),

that the day should be his, and that he and those who had charge of him should have the honour of it.

It is said that the prince was thrown to the ground11 and was rescued by Richard de Beaumont, who carried the banner of Wales, and who threw the

banner over the prince, bestrode his body, and beat back his assailants.12 Harcourt now sent to Arundel for help, and

he forced back the French, who had probably by this time advanced to the rising ground of the English position. A flank attack on the side of Wadicourt was

next made by the Counts of Alençon and Ponthieu, but the English were strongly entrenched there, and the French were unable to penetrate the defences

and lost the Duke of Lorraine and the Counts of Alençon and Blois.

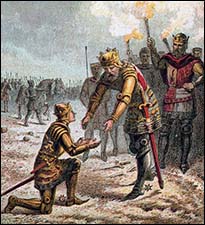

The two front lines of their army were utterly broken before King Philip's division engaged. Then Edward appears to have advanced at the head of the reserve,

and the rout soon became complete.When Edward met his son after the battle was over, he embraced him and declared that he had acquitted himself loyally, and

the prince bowed low and did reverence to his father. The next day he joined the king in paying funeral honours to the King of Bohemia.13

The two front lines of their army were utterly broken before King Philip's division engaged. Then Edward appears to have advanced at the head of the reserve,

and the rout soon became complete.When Edward met his son after the battle was over, he embraced him and declared that he had acquitted himself loyally, and

the prince bowed low and did reverence to his father. The next day he joined the king in paying funeral honours to the King of Bohemia.13

It is commonly said that the prince received the name of the Black Prince after the battle of Crécy, and that he was so called

because he wore black armour at the battle. The first recorded notices of the appellation seem to be given by Leland14 in a heading to the 'Itinerary'

extracted from 'Eulogium.' The 'Black Prince,' however, is not in the 'Eulogium' of the Rolls Series, except in the editor's marginal notes. Leland15

repeats the appellation in quotations 'owte of a booke of chroniques in Peter College Library.' This 'booke' is a transcript from a copy of Caxton's 'Chronicle,'

with the continuation by Dr. John Warkworth, master of the college, 1473-98.16 The manuscript has Warwork's autograph, 'monitum,' but on examination

is found not to contain the words 'Black Prince.'

Other early writers who give Edward his well-known title are: Grafton (1563), who writes,17 'Edward, prince of Wales, who was called the blacke

prince;' Holinshed18; Shakespeare, 'Henry V,' II. iv. 56; and in Speed. Barnes, 'History of Edward III' (1688), p. 363, says: 'From this time the

French began to call him Le Neoir or the Black Prince,' and gives a reference which implies that the appellation is found in a record of 2 Richard II, but his

reference does not appear sufficiently clear to admit of verification.

The name does not occur in the 'Eulogium,' the 'Chronicle' of Geoffrey le Baker, the 'Chronicon Angliæ,' the 'Polychronicon' of Higden or of Trevisa, or

in Caxton's 'Chronile' (1482), nor is it used by Jehan le Bel or Froissart. Jehan de Wavrin (d.1474?), who expounds a prophecy of Merlin as applying to the

prince, says that he was called 'Pie-de-Plomb.'19 Louandre20 asserts that before the battle Edward arrayed his son in black armour, and

it seems that the prince used black in his heraldic devices.21 It is evident from the notices of the sixteenth-century historians that when they

wrote the name was traditional.22

As regards the story that the prince took the crest of three ostrich

feathers and the motto 'Ich dien' from the king of Bohemia, who was slain in the battle of Crécy, it may be noted, first, as

to the ostrich feathers, that in the manuscript of John of Arderne's ' Medica,' written by William Seton,23 is an ostrich feather used as a mark

of reference to a previous page, on which the same device occurs, 'ubi depingitur penna principis Walliæ,' with the remark: 'Et nota quod talem pennam

albam portabat Edwardus, primogenitus E. regis Angliæ, super eristam suam, et illam pennam conquisivit de Rege Boemiæ, quern interfecit apud

Cresy in francia.'24 Although the reference and remark in Sloane MS. 56 may be by Seton and not by Arderne, the prince's physician, it is evident

that probably before the prince's death the ostrich feather was recognised as his peculiar badge, assumed after the battle of Crécy. As regards the story that the prince took the crest of three ostrich

feathers and the motto 'Ich dien' from the king of Bohemia, who was slain in the battle of Crécy, it may be noted, first, as

to the ostrich feathers, that in the manuscript of John of Arderne's ' Medica,' written by William Seton,23 is an ostrich feather used as a mark

of reference to a previous page, on which the same device occurs, 'ubi depingitur penna principis Walliæ,' with the remark: 'Et nota quod talem pennam

albam portabat Edwardus, primogenitus E. regis Angliæ, super eristam suam, et illam pennam conquisivit de Rege Boemiæ, quern interfecit apud

Cresy in francia.'24 Although the reference and remark in Sloane MS. 56 may be by Seton and not by Arderne, the prince's physician, it is evident

that probably before the prince's death the ostrich feather was recognised as his peculiar badge, assumed after the battle of Crécy.

While the crest of John of Bohemia was the entire wings of a vulture 'besprinkled with linden leaves of gold,'25 the ostrich seems to have been

the badge of his house; it was borne by Queen Anne of Bohemia, as well as by her brother Wenzel, and is on her effigy on her tomb.26 The feather

badge occurs as two feathers on four seals of the prince,27 and as three feathers on the alternate escutcheons placed on his tomb in accordance

with the directions of his will. The prince in his will says that the feathers were 'for peace,' i.e. for jousts and tournaments, and calls them his badge,

not his crest. Although the ostrich feather was his special badge, it was placed on some plate belonging to his mother, was used in the form of one or more

feathers by various members of the royal house, and, by grant of Richard II, by

Thomas Mowbray, Duke of Norfolk.28 The story of the prince's winning the feathers was printed, probably for the

first time, by Camden in his 'Remaines.' In his first edition (1605) he states that it was 'at the battle of Poictiers,' p. 161,

but corrects this in his next edition (1614), p. 214.

Secondly, as to the motto, it appears that the prince used two mottoes, 'Houmout' and 'Ich dien,' which are both appended as signature to a letter under

his privy seal.29 In his will he directed that 'Houmout' should be written on each of the escutcheons round his tomb. But it actually occurs

only over the escutcheons bearing his arms, while over the alternate escutcheons with his badge, and also on the escroll upon the quill of each feather,

are the words 'ich diene' (sic). 'Houmout' is interpreted as meaning high mood or courage.30 No early tradition connects 'Ich dien'

with John of Bohemia. Like 'Houmout,' it is probably old Flemish or Low German. Camden in his 'Remaines' (in the passage cited above) says that it is old

English, 'Ic dien,' that is 'I serve,' and that the prince 'adjoyned' the motto to the feathers, and he connects it, no doubt rightly, with the prince's

position as heir, referring to Ep. to Galatians, iv. 1.

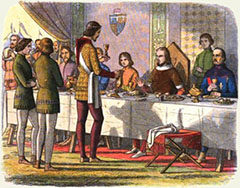

The prince was present at the siege of Calais, and after the surrender of the town harried and burned the country for

thirty miles round, and brought much

booty back with him.31 He returned to England with his father on 12 Oct. 1347, took part in the jousts and other festivities of the court, and

was invested by the king with the new order of the Garter. He shared in the king's chivalrous expedition to Calais in the last days of 1349, came to the

rescue of his father, and when the combat was over and the king and his prisoners sat down to feast, he and the other English knights served the king and his

guests at the first course and then sat down to meat at another table.32

The prince was present at the siege of Calais, and after the surrender of the town harried and burned the country for

thirty miles round, and brought much

booty back with him.31 He returned to England with his father on 12 Oct. 1347, took part in the jousts and other festivities of the court, and

was invested by the king with the new order of the Garter. He shared in the king's chivalrous expedition to Calais in the last days of 1349, came to the

rescue of his father, and when the combat was over and the king and his prisoners sat down to feast, he and the other English knights served the king and his

guests at the first course and then sat down to meat at another table.32

When the king embarked at Winchelsea on 28 Aug. 1350 to intercept the fleet of La Cerda, the prince sailed with him, though in another ship, and in company

with his brother, the young Earl of Richmond (John of Gaunt). His ship was grappled by a large Spanish ship and was so full of leaks

that it was likely to sink, and though he and his knights attacked the enemy manfully, they were unable to take her. The Earl of Lancaster

came to his rescue and attacked the Spaniard on the other side; she was soon taken, her crew were thrown into the sea, and as the prince and his men got on

board her their own ship foundered.33

In 1353 some disturbances seem to have broken out in Cheshire, for the prince as earl marched with the Duke of Lancaster to the neighbourhood of Chester

to protect the justices, who were holding an assize there. The men of the earldom offered to pay him a heavy fine to bring the

assize to an end, but when they thought they had arranged matters the justices opened an inquisition of trailbaston, took a

large sum of money from them, and seized many houses and much land into the prince's, their earl's, hands. On his return from Chester the prince is said

to have passed by the abbey of Dieulacres in Stafordshire, to have seen a noble church which his grandfather, Edward I, had built there, and to have granted

five hundred marks, a tenth of the sum he had taken from his earldom, towards its completion; the abbey was almost certainly not Dieulacres but Vale Royal.34

When Edward determined to renew the war with France in 1355, he ordered the prince to lead an army into Aquitaine while he, as

his plan was, acted with the king of Navarre in Normandy, and the Duke of Lancaster upheld the cause of Montfort in Brittany.

The prince's expedition was made in accordance with the request of some of the Gascon lords who were anxious for plunder. On 10 July the king appointed him

his lieutenant in Gascony, and gave him powers to act in his stead, and, on 4 Aug., to receive homages.35 He left London for Plymouth on 30 June,

was detained there by contrary winds, and set sail on 8 Sept. with about three hundred ships, in company with the Earls of Warwick [Thomas de Beauchamp, 11th earl],

Suffolk, Salisbury, and Oxford, and in command of a thousand men-at-arms,

two thousand archers, and a large body of Welsh foot.36

At Bordeaux the Gascon lords received him with much rejoicing. It was decided to make a short campaign before the winter, and on 10 Oct. he set out with

fifteen hundred lances, two thousand archers, and three thousand light foot. Whatever scheme of operations the king may have formed during the summer,

this expedition of the prince was purely a piece of marauding. After grievously harrying the counties of Juliac, Armagnac, Astarac, and part of Comminges,

he crossed the Garonne at Ste.-Marie a little above Toulouse, which was occupied by the Count of Armagnac and a considerable force. The count refused to

allow the garrison to make a sally, and the prince passed on, stormed and burnt Mont Giscar, where many men, women, and children were ill-treated and

slain,37 and took and pillaged Avignonet and Castelnaudary.

All the country was rich, and the people 'good, simple, and ignorant of war,' so the prince took great spoil, especially of carpets, draperies, and

jewels, for 'the robbers' spared nothing, and the Gascons who marched with him were specially greedy.38 Carcassonne was taken and sacked,

but he did not take the citadel, which was strongly situated and fortified. Ourmes (or Homps, near Narbonne) and Trébes bought off his army.

He plundered Narbonne and thought of attacking the citadel, for he heard that there was much booty there, but gave up the idea on finding that it

was well defended. While he was there a messenger came to him from the papal court, urging him to allow negotiations for peace. He replied that he

could do nothing without knowing his father's will.39

From Narbonne he turned to march back to Bordeaux. The Count of Armagnac tried to intercept him, but a small body of French having been defeated in

a skirmish near Toulouse the rest of the army retreated into the city, and the prince returned in peace to Bordeaux, bringing back with him enormous

spoils. The expedition lasted eight weeks, during which the prince only rested eleven days in all the places he visited, and without performing any

feat of arms did the French king much mischief.40 During the next month, before 21 Jan. 1350, the leaders under his command reduced five

towns and seventeen castles.41

On 6 July [1356] the prince set out on another expedition, undertaken with the intention of passing through France to Normandy, and there giving aid to his

father's Norman allies, the party headed by the king of Navarre and Geoffrey Harcourt. In Normandy he expected, he says, to be met by his father.42

He crossed the Dordogne at Bergerac on 4 Aug.,43 and rode through Auvergne, Limousin, and Berry, plundering and burning as he went until

he came to Bourges, where he burnt the suburbs but failed to take the city. He then turned westward and made an unsuccessful attack on Issoudun,

25-7 Aug. Meanwhile King John was gathering a large force at Chartres, whence he was able to defend the passages of the Loire, and was sending troops

to the fortresses that seemed in danger of attack.

From Issoudun the prince returned to his former line of march and took Vierzon. There he learnt that it would be impossible for him to cross the Loire

or to form a junction with Lancaster, who was then in Brittany. Accordingly he determined to return to Bordeaux by way

of Poitiers, and after putting to death most of the garrison of the castle of Vierzon set out on the 29th towards Romorantin. Some French knights who

skirmished with his advanced guard retreated into that place, and when he heard it he said: 'Let us go there; I should like to see them a little nearer.'

He inspected the fortress in person and sent his friend Chandos to summon the garrison to surrender. The place was defended by Boucicault and other

leaders, and on their refusing his summons he assaulted it on the 31st. The siege lasted three days, and the prince, who was enraged at the death of

one of his friends, declared that he would not leave the place untaken. Finally he set fire to the roofs of the fortress by using Greek fire,

reduced it on 3 Sept., and on the 6th proceeded on his march through Berry.

On the 9th King John, who had now gathered a large force, crossed the Loire at Blois and went in pursuit of him. When the king was at Loches on the

12th he had as many as twenty thousand men-at-arms, and with these and his other forces he advanced to Chauvigny. On the 16th and 17th his army crossed

the Vienne. Meanwhile the prince was marching almost parallel to the French and at only a few miles distance from them. It is impossible to believe

Froissart's statement that he was ignorant of the movements of the French. From the 14th to the 16th he was at Châtelherault, and on the next

day, Saturday, as he was marching towards Poitiers, some French men-at-arms skirmished with his advance guard, pursued them up to the main body of

his army, and were all slain or taken prisoners. The French king had outstripped him, and his retreat was cut off by an army at least fifty thousand

strong, while he had not, it is said, more than about two thousand men-at-arms, four thousand archers, and fifteen hundred light foot. Lancaster had

endeavoured to come to his relief, but had been stopped by the French at Pont-de-Cé.44

When the prince knew that the French army lay between him and Poitiers, he took up his position on some rising ground to

the south-east of the city, between the right bank of the Miausson and the old Roman road, probably on a spot now called La Cardinerie, a farm in

the commune of Beauvoir, for the name Maupertuis has long gone out of use, and remained there that night. The next day, Sunday, the 18th, the cardinal,

Hélie Talleyrand, called 'of Périgord,' obtained leave from John to endeavour to make peace. The prince was willing enough to come to terms,

and offered to give up all the towns and castles he had conquered, to set free all his prisoners, and not to serve against the king of

France for seven years, besides, it is said, offering a payment of a hundred thousand francs. King John, however, was persuaded to demand that the prince

and a hundred of his knights should surrender themselves up as prisoners, and to this he would not consent. The cardinal's negotiations lasted the whole day,

and were protracted in the interest of the French, for John was anxious to give time for further reinforcements to join his army.

Considering the position in which the prince then was, it seems probable that the French might have destroyed his little army simply by hemming it in

with a portion of their host, and so either starving it or forcing it to leave its strong station and fight in the open with the certainty of defeat.

Anyway John made a fatal mistake in allowing the prince the respite of Sunday; for while the negotiations were going forward he employed his army in

strengthening its position. The English front was well covered by vines and hedges; on its left and rear was the ravine of the Miausson and a good

deal of broken ground, and its right was flanked by the wood and abbey of Nouaillé. All through the day the army was busily engaged in digging

trenches and making fences, so that it stood, as at Crécy, in a kind of entrenched camp.45

The prince drew up his men in three

divisions, the first being commanded by Warwick and Suffolk, the second by himself, and the rear by

Salisbury and Oxford. The French were drawn up in four divisions, one behind the other, and so

lost much of the advantage of their superior numbers. In front of his first line and on either side of the narrow lane that led to his position the

prince stationed his archers, who were well protected by hedges, and posted a kind of ambush of three hundred men-at-arms and three-hundred mounted

archers, who were to fall on the flank of the second battle of the enemy, commanded by the Duke of Normandy.

At daybreak on the 19th the prince addressed his little army, and the fight began. An attempt was made by three hundred picked men-at-arms to ride

through the narrow lane and force the English position, but they were shot down by the archers. A body of Germans and the first division of the army

which followed were thrown into disorder; then the English force in ambush charged the second division on the flank, and as it began to waver the

English men-at-arms mounted their horses, which they had kept near them, and charged down the hill. The prince kept Chandos by his side, and his

friend did him good service in the fray. As they prepared to charge he cried: 'John, get forward; you shall not see me turn my back this day, but

I will be ever with the foremost,' and then he shouted to his banner-bearer, 'Banner, advance, in the name of God and St. George!'

All the French except the advance guard fought on foot, and the division of the Duke of Normandy, already wavering, could not stand against the English charge

and fled in disorder. The next division, under the Duke of Orleans, also fled, though not so shame-fully, but the rear, under the king in person,

fought with much gallantry. The prince, 'who had the courage of a lion, took great delight that day in the fight.' The combat lasted till a little after

3 P.M., and the French, who were utterly defeated, left eleven thousand dead on the field, of whom 2,426 were

men of gentle birth. Nearly a hundred counts, barons, and bannerets and two thousand men-at-arms, besides many others, were made prisoners, and

the king and his youngest son, Philip, were among those who were taken. The English loss was not large.

When the king was brought to him the prince received him with respect, helped him to take off his armour, and entertained him and the greater part

of the princes and barons who had been made prisoners at supper. He served at the king's table and would not sit down with him, declaring that

'he was not worthy to sit at table with so great a king or so valiant a man,' and speaking many comfortable words to him, for which the

French praised him highly.46

The next day the prince continued his retreat on Bordeaux; he marched warily, but no one ventured to attack him. At Bordeaux, which he reached

on 2 Oct., he was received with much rejoicing, and he and his men tarried there through the winter and wasted in festivities the immense spoil

they had gathered. On 23 March 1357 he concluded a two years' truce, for he wished to return home. The Gascon lords were unwilling that the king

should be carried off to England, and he gave them a hundred thousand crowns to silence their murmurs. He left the country under the government

of four Gascon lords and arrived in England on 4 May, after a voyage of eleven days, landing at Plymouth,47 not at Sandwich.48

When he entered London in triumph on the 24th, the king, his prisoner, rode a fine white charger, while he was mounted on a little black hackney.

Judged by modern ideas the prince's show of humility appears affected, and the Florentine chronicler remarks that the honour done to King John

must have increased the misery of the captive and magnified the glory of King Edward; but this comment argues a refinement of feeling which

neither Englishmen nor Frenchmen of that day had probably attained.49

After his return to England the prince took part in the many festivals and tournaments of his father's court, and in May 1359 he and the king

and other challengers held the lists at a joust proclaimed at London by the mayor and sheriffs, and, to the great delight of the citizens,

the king appeared as the mayor and the prince as the senior sheriff.50 Festivities of this sort and the lavish gifts he bestowed

on his friends brought him into debt, and on 27 Aug., when a new expedition into France was being prepared, the king granted that if he fell

his executors should have his whole estate for four years for the payment of his debts.51 In October he sailed with the king to

Calais, and led a division of the army during the campaign that followed. At its close he took the principal part on the English side in

negotiating the treaty of Bretigny, and the preliminary truce arranged at Chartres on 7 May 1360 was drawn up by proctors acting in his name

and the name of the regent of France.52

He probably did not return to England until after his father, 53 who landed at Rye on 18 May. On 9 July he and

Henry, duke of Lancaster, landed at Calais in attendance on the French king. As, however, the stipulated

instalment of the king's ransom was not ready, he returned to England, leaving John in charge of Sir Walter Manny and three other knights.54

He accompanied his father to Calais on 9 Oct. to assist at the liberation of King John and the ratification of the treaty, rode with John

to Boulogne, where he made his offering in the Church of the Virgin, and returned with his father to England at the beginning of November.

On 10 Oct. 1361 the prince, who was then in his thirty-first year, married his cousin Joan, countess of Kent,

daughter of Edmund of Woodstock, earl of Kent, younger son of Edward I, by Margaret, daughter of Philip III

of France, and widow of Thomas lord Holland, and in right of his wife earl of Kent, then in her thirty-third year,

and the mother of three children. As the prince and the countess were related in the third degree, and also by the spiritual tie of sponsorship,

the prince being godfather to Joan's elder son Thomas, a dispensation was obtained for their marriage from Innocent VI,

though they appear to have been contracted before it was applied for.55 The marriage was performed at Windsor,

in the presence of the king, by Simon, archbishop of Canterbury. It is said that the marriage—that is, no doubt, the contract of marriage—was

entered into without the knowledge of the king.56 The prince and his wife resided at Berkhampstead in Hertfordshire.

On 19 July 1362 the king granted him all his dominions in Aquitaine and Gascony, to be

held as a principality by liege homage on payment of an ounce of gold each year, together with the title of Prince of Aquitaine and Gascony.57

During the rest of the year he was occupied in preparing for his departure to his new principality, and after Christmas he received the king

and his court at Berkhampstead, took leave of his father and mother, and in the following February sailed with his wife and all his household

for Gascony, and landed at Rochelle. There he was met by Chandos, the king's lieutenant, and proceeded with him to Poitiers, where he received

the homage of the lords of Poitou and Saintonge; he then rode to various cities and at last came to Bordeaux, where from 9 to 30 July he received

the homage of the lords of Gascony. He received all graciously, and kept a splendid court, residing sometimes at Bordeaux and sometimes at Angoulême. On 19 July 1362 the king granted him all his dominions in Aquitaine and Gascony, to be

held as a principality by liege homage on payment of an ounce of gold each year, together with the title of Prince of Aquitaine and Gascony.57

During the rest of the year he was occupied in preparing for his departure to his new principality, and after Christmas he received the king

and his court at Berkhampstead, took leave of his father and mother, and in the following February sailed with his wife and all his household

for Gascony, and landed at Rochelle. There he was met by Chandos, the king's lieutenant, and proceeded with him to Poitiers, where he received

the homage of the lords of Poitou and Saintonge; he then rode to various cities and at last came to Bordeaux, where from 9 to 30 July he received

the homage of the lords of Gascony. He received all graciously, and kept a splendid court, residing sometimes at Bordeaux and sometimes at Angoulême.

He appointed Chandos constable of Guyenne, and provided the knights of his household with profitable offices. They kept much state, and their

extravagance displeased the people.58 Many of the Gascon lords were dissatisfied at being handed over to the dominion of the English,

and the favour the prince showed to his own countrymen, and the ostentatious magnificence they exhibited, increased this feeling of dissatisfaction.

The lord of Albret and many more were always ready to give what help they could to the French cause, and the Count of Foix, though he visited

the prince on his first arrival, was thoroughly French at heart, and gave some trouble in 1365 by refusing to do homage for Bearn.59

Charles V, who succeeded to the throne of France in April 1364, was careful to encourage the malcontents, and the prince's position was by no

means easy. In April 1363 the prince mediated between the Counts of Foix and Armagnac, who had for a long time been at war with each other.

He also attempted in the following February to mediate between Charles of Blois and John of Montfort, the rival competitors for the duchy

of Brittany. Both appeared before him at Poitiers, but his mediation was unsuccessful. The next month he entertained the king of Cyprus at

Angoulême, and held a tournament there. At the same time he and his lords excused themselves from assuming the cross. During the

summer the lord of Albret was at Paris, and his forces and several other Gascon lords upheld the French cause in Normandy against the party

of Navarre. Meanwhile war was renewed in Brittany; the prince allowed Chandos to raise and lead a force to succour the party of Montfort,

and Chandos won the battle of Auray against the French.

As the leaders of the free companies which desolated France were for the most part Englishmen or Gascons, they did not ravage Aquitaine, and

the prince was suspected, probably not without cause, of encouraging, or at least of taking no pains to discourage, their proceedings.60

Accordingly on 14 Nov. 1364 Edward called upon him to restrain their ravages.61 In 1365 these companies, under Sir Hugh Calveley

and other leaders, took service with Du Guesclin, who employed them in 1366 in compelling Peter of Castile to flee from his kingdom, and

in setting up his bastard brother, Henry of Trastamare, as king in his stead. Peter, who was in alliance with King Edward, sent messengers

to the prince asking his help, and on receiving a gracious answer at Corunna, set out at once, and arrived at Bayonne with his son and his

three daughters. The prince met him at Cap Breton, and rode with him to Bordeaux.

Many of his lords, both English and Gascon, were unwilling that he should espouse Peter's cause, but he declared that it was not fitting

that a bastard should inherit a kingdom, or drive out his lawfully born brother, and that no king or king's son ought to suffer such a

despite to royalty; nor could any turn him from his determination to restore the king. Peter won friends by declaring that he would make

Edward's son king of Galicia, and would divide his riches among those who helped him. A parliament was held at Bordeaux, in which it was

decided to ask the wishes of the English king. Edward replied that it was right that his son should help Peter, and the prince held another

parliament at which the king's letter was read. Then the lords agreed to give their help, provided that their pay was secured to them.

In order to give them the required security, the prince agreed to lend Peter whatever money was necessary.

He and Peter then held a conference with Charles of Navarre at Bayonne, and agreed with him to allow their troops to pass through his

dominions. In order to persuade him to do this, Peter had, besides other grants, to pay him 56,000 florins, and this sum was lent him

by the prince. On 23 Sept. a series of agreements were entered into between the prince, Peter, and Charles of Navarre, at Libourne, on

the Dordogne, by which Peter covenanted to put the prince in possession of the province of Biscay and the territory and fortress of

Castro de Urdialès as pledges for the repayment of this debt, to pay 550,000 florins for six months' wages at specified dates,

250,000 florins being the prince's wages, and 300,000 florins the wages of the lords who were to serve in the expedition. He consented

to leave his three daughters in the prince's hands as hostages for the fulfilment of these terms, and further agreed that whenever the

king, the prince, or their heirs, the kings of England, should march in person against the Moors, they should have the command of the

van before all other christian kings, and that if they were not present the banner of the king of England should be carried in the

van side by side with the banner of Castile.62

The prince received a hundred thousand francs from his father out of the ransom of the late king of France,63 and broke up

his plate to help to pay the soldiers he was taking into his pay. While his army was assembling he remained at Angoulême, and

was there visited by Peter.64 He then stayed over Christmas at Bordeaux, for his wife was there brought to bed of her

second son Richard. He left Bordeaux early in February, and joined his army at Dax, where he remained

three days, and received a reinforcement of four hundred men-at-arms and four hundred archers sent out by his father under his

brother John, duke of Lancaster. From Dax he advanced by St. Jean-Pied-de-Port through Roncesvalles to

Pamplona. When Calveley and other English and Gascon leaders of free companies found that he was about to fight for Peter, they

threw up the service of Henry of Trastamare, and joined him 'because he was their natural lord.'65

While he was at Pamplona he received a letter of defiance from Henry.66 From Pamplona he marched by Arruiz to Salvatierra,

which opened its gates to his army, and thence advanced to Vittoria, intending to march on Burgos by this direct route. A body of his

knights, which he had sent out to reconnoitre under Sir William Felton, was defeated by a skirmishing party, and he found that Henry

had occupied some strong positions, and especially St. Domingo de la Calzada on the right of the Ebro, and Zaldiaran on the left,

which made it impossible for him to reach Burgos through Alava. Accordingly he crossed the Ebro, and encamped under the walls of

Logroño. During these movements his army had suffered from want of provisions both for men and horses, and from wet and windy

weather. At Logroño, however, though provisions were still scarce, they were somewhat better off, and there on 30 March the

prince wrote an answer to Henry's letter. On 2 April he quitted Logroño and moved to Navarrete de Rioja. Meanwhile Henry and

his French allies had encamped at Najara, so that the two armies were now near each other.

Letters passed between Henry and the prince, for Henry seems to have been anxious to make terms. He declared that Peter was a tyrant,

and had shed much innocent blood, to which the prince replied that the king had told him that all the persons he had slain were

traitors. The next morning the prince's army marched from Navarrete, and all dismounted while they were yet some distance from

Henry's army. The van, in which were three thousand men-at-arms, both English and Bretons, was led by Lancaster,

Chandos, Calveley, and Clisson; the right division was commanded by Armagnac and other Gascon lords; the left, in which some

German mercenaries marched with the Gascons, by the Captal de Buch and the Count of Foix; and the rear or main battle by the prince,

with three thousand lances, and with the prince was Peter and, a little on his right, the dethroned king of Majorca and his company;

the numbers, however, are scarcely to be depended on.

Before the battle began the prince prayed aloud to God that as he had come that day to uphold the right and reinstate a disinherited king,

God would grant him success. Then, after telling Peter that he should know that day whether he should have his kingdom or not, he cried:

'Advance, banner, in the name of God and St. George; and God defend our right.' The knights of Castile teased his van sorely, but the

wings of Henry's army behaved ill, and would not move, so that the Gascon lords were able to attack the main body on the flanks.

Then the prince brought the main body of his army into action, and the fight became hot, for he had under him 'the flower of chivalry,

and the most famous warriors in the whole world.' At length Henry's van gave way, and he fled from the field.67

When the battle was over the prince besought Peter to spare the lives of those who had offended him. Peter assented, with the exception

of one notorious traitor, whom he at once put to death, and he also had two others slain the next day. Among the prisoners was the French

marshal Audeneham, whom the prince had formerly taken prisoner at Poitiers, and whom he had released on his

giving his word that he would not bear arms against him until his ransom was paid. When the prince saw him he reproached him bitterly,

and called him 'liar and traitor.' Audeneham denied that he was either, and the prince asked him whether he would submit to the judgment

of a body of knights. To this Audeneham agreed, and after he had dined the prince chose twelve knights, four English, four Gascons, and

four Bretons, to judge between himself and the marshal. After he had stated his case, Audeneham replied that he had not broken his word,

for the army the prince led was not his own; he was merely in the pay of Peter. The knights considered that this view of the prince's

position was sound, and gave their verdict for Audeneham.68

When the battle was over the prince besought Peter to spare the lives of those who had offended him. Peter assented, with the exception

of one notorious traitor, whom he at once put to death, and he also had two others slain the next day. Among the prisoners was the French

marshal Audeneham, whom the prince had formerly taken prisoner at Poitiers, and whom he had released on his

giving his word that he would not bear arms against him until his ransom was paid. When the prince saw him he reproached him bitterly,

and called him 'liar and traitor.' Audeneham denied that he was either, and the prince asked him whether he would submit to the judgment

of a body of knights. To this Audeneham agreed, and after he had dined the prince chose twelve knights, four English, four Gascons, and

four Bretons, to judge between himself and the marshal. After he had stated his case, Audeneham replied that he had not broken his word,

for the army the prince led was not his own; he was merely in the pay of Peter. The knights considered that this view of the prince's

position was sound, and gave their verdict for Audeneham.68

On 5 April the prince and Peter marched to Burgos, and there kept Easter. The prince, however, did not take up his quarters in the city,

but camped outside the walls at the monastery of Las Helgas. Peter did not pay him any of the money he owed him, and he could get nothing

from him except a solemn renewal of his bond of the previous 23 Sept., which he made on 2 May before the high altar of the cathedral of

Burgos.69 By this time the prince began to suspect his ally of treachery. Peter had no intention of paying his debts, and when

the prince demanded possession of Biscay told him that the Biscayans would not consent to be handed over to him. In order to get rid of

his creditor he told him that he could not get money at Burgos, and persuaded the prince to take up his quarters at Valladolid while he

went to Seville, whence he declared he would send the money he owed.

The prince remained at Valladolid during some very hot weather, waiting in vain for his money. His army suffered so terrible from dysentery

and other diseases that it is said that scarcely one Englishman out of five ever saw England again.70 He was himself seized with

a sickness from which he never thoroughly recovered, and which some said was caused by poison.71 Food and drink were scarce,

and the free companies in his pay did much mischief to the surrounding country.72 Meanwhile Henry of Trastamare made war upon

Aquitaine, took Bagnères and wasted the country. Fearing that Charles of Navarre would not allow him to return through his dominions,

the prince negotiated with the king of Aragon for a passage for his troops. The king made a treaty with him, and when Charles of Navarre

heard of it he agreed to allow the prince, the Duke of Lancaster, and some of their lords to pass through

his country; so they returned through Roncesvalles, and reached Bordeaux early in September.

Some time after he had returned the companies, some six thousand strong, also reached Aquitaine, having passed through Aragon. As they had

not received the whole of the money the prince had agreed to pay them, they took up their quarters in his country and began to do much

mischief. He persuaded the captains to leave Aquitaine, and the companies under their command crossed the Loire and did much damage to

France. This greatly angered Charles V, who about this time did the prince serious mischief by encouraging disaffection among the

Gascon lords. When the prince was gathering his army for his Spanish expedition, the lord of Albret agreed to serve with a thousand lances.

Considering, however, that he had at least as many men as he could find provisions for, the prince on 8 Dec. 1366 wrote to him requesting

that he would bring two hundred lances only.

The lord of Albret was much incensed at this, and, though peace was made by his uncle the Count of Armagnac, did not forget the offence,

and Froissart speaks of it as the 'first cause of hatred between him and the prince.' A more powerful cause of this lord's discontent

was the non-payment of an annual pension which had been granted him by Edward. About this time he agreed to marry Margaret of Bourbon,

sister of the queen of France. The prince was much vexed at this, and, his temper probably being soured by sickness and disappointment,

behaved with rudeness to both D'Albret and his intended bride. On the other hand, Charles offered the lord the pension which he had lost,

and thus drew him and his uncle, the Count of Armagnac, altogether over to the French side.

The immense cost of the late campaign and his constant extravagance had brought the prince into difficulties, and as soon as he returned

to Bordeaux he called an assembly of the estates of Aquitaine to meet at St. Emilion in order to obtain a grant from them. It seems as

though no business was done then, for in January 1368 he held a meeting of the estates at Angoulême, and there prevailed on them

to allow him a fouage, or hearth-tax, of ten sous for five years. An edict for this tax was published on 25 Jan. The chancellor,

John Harewell, held a conference at Niort, at which he persuaded the barons of Poitou, Saintonge, Limousin, and Rouergue to agree to

this tax, but the great vassals of the high marches refused, and on 30 June and again on 25 Oct. the Counts of Armagnac, Périgord,

and Comminges, and the lord of Albret laid their complaints before the king of France, declaring that he was their lord paramount.73

Meanwhile the prince's friend Chandos, who strongly urged him against imposing this tax, had retired to his Norman estate.

Charles took advantage of these appeals, and on 25 Jan. 1369 sent messengers to the prince, who was then residing at Bordeaux, summoning

him to appear in person before him in Paris and there receive judgment. He replied: 'We will willingly attend at Paris on the day appointed

since the king of France sends for us, but it shall be with our helmet on our head and sixty thousand men in our company.' He caused the

messengers to be imprisoned, and in revenge for this the Counts of Périgord and Comminges and other lords set on the high-steward

of Rouergue, slew many of his men, and put him to flight. The prince sent for Chandos, who came to his help, and some fighting took place,

though war was not yet declared. His health was now so feeble that he could not take part in active operations, for he was swollen with

dropsy and could not ride. By 18 March more than nine hundred towns, castles, and other places signified in one way or another their

adherence to the French cause.74

He

had already warned his father of the intentions of the French king, but there was evidently a party at Edward's court that was jealous

of his power, and his warnings were slighted. In April, however, war was declared. Edward sent the Earls of Cambridge

and Pembroke [John Hastings, 2nd Earl] to his assistance, and Sir Robert Knolles, who now in took service with him, added much to his

strength. The war in Aquitaine was desultory, and, though the English maintained their ground fairly in the field, every day that it

was prolonged weakened their hold on the country. On 1 Jan. 1370 the prince sustained a heavy loss in the death of his friend Chandos.

Several efforts were made by Edward to conciliate the Gascon lords, but they were fruitless and can only have served to weaken the

prince's authority. It is probable that John of Gaunt was working against him at the English court, and when

he was sent out in the summer to help his brother, he came with such extensive powers that he almost seemed as though he had come to

supersede him. He

had already warned his father of the intentions of the French king, but there was evidently a party at Edward's court that was jealous

of his power, and his warnings were slighted. In April, however, war was declared. Edward sent the Earls of Cambridge

and Pembroke [John Hastings, 2nd Earl] to his assistance, and Sir Robert Knolles, who now in took service with him, added much to his

strength. The war in Aquitaine was desultory, and, though the English maintained their ground fairly in the field, every day that it

was prolonged weakened their hold on the country. On 1 Jan. 1370 the prince sustained a heavy loss in the death of his friend Chandos.

Several efforts were made by Edward to conciliate the Gascon lords, but they were fruitless and can only have served to weaken the

prince's authority. It is probable that John of Gaunt was working against him at the English court, and when

he was sent out in the summer to help his brother, he came with such extensive powers that he almost seemed as though he had come to

supersede him.

In the spring Charles raised two large armies for the invasion of Aquitaine; one, under the Duke of Anjou, was to enter Guyenne by

La Réole and Bergerac, the other, under the Duke of Berry, was to march towards Limousin and Queray, and both were to unite and

besiege the prince in Angoulême. Ill as he was, the prince left his bed of sickness75 and gathered an army at Cognac,

where he was joined by the Barons of Poitou and Saintonge, and the Earls of Cambridge, Lancaster,

and Pembroke. The two French armies gained many cities, united and laid siege to Limoges, which was treacherously surrendered to them

by the bishop, who had been one of the prince's trusted friends. When the prince heard of the surrender, he swore 'by the soul of his

father' that he would have the place again and would make the inhabitants pay dearly for their treachery. He set out from Cognac with

an army of twelve hundred lances, a thousand archers, and three thousand foot. His sickness was so great that he was unable to mount

his horse, and was carried in a litter.

The success of the French in Aquitaine was checked about this time by the departure of Du Guesclin, who was summoned to the north to

stop the ravages of Sir Robert Knolles. Limoges made a gallant defence, and the prince determined to take it by undermining the walls.

His mines were constantly countermined by the garrison, and it was not until the end of October, after a month's siege, that his

miners succeeded in demolishing a large piece of wall which filled the ditches with its ruins. The prince ordered that no quarter

should be given, and a terrible massacre took place of persons of all ranks and ages. Many piteous appeals were made to him for

mercy, but he would not hearken, and three thousand men, women, and children are said to have been put to the sword. When the

bishop was brought before him, he told him that his head should be cut off, but Lancaster begged him of his brother, and so, while

so many innocent persons were slain, the life of the chief offender was spared. The city was pillaged and burnt.76

The success of the French in Aquitaine was checked about this time by the departure of Du Guesclin, who was summoned to the north to

stop the ravages of Sir Robert Knolles. Limoges made a gallant defence, and the prince determined to take it by undermining the walls.

His mines were constantly countermined by the garrison, and it was not until the end of October, after a month's siege, that his

miners succeeded in demolishing a large piece of wall which filled the ditches with its ruins. The prince ordered that no quarter

should be given, and a terrible massacre took place of persons of all ranks and ages. Many piteous appeals were made to him for

mercy, but he would not hearken, and three thousand men, women, and children are said to have been put to the sword. When the

bishop was brought before him, he told him that his head should be cut off, but Lancaster begged him of his brother, and so, while

so many innocent persons were slain, the life of the chief offender was spared. The city was pillaged and burnt.76

The prince returned to Cognac; his sickness increased, and he was forced to give up all hope of being able to direct any further

operations and to proceed first to Angoulême and then to Bordeaux. The death of his eldest son Edward, which happened at

this time, grieved him greatly; he became worse, and his surgeon advised him to return to England. He left Aquitaine in charge

of Lancaster, landed at Southampton early in January 1371, met his father at Windsor,

and put a stop to a treaty the king had made the previous month with Charles of Navarre, for he would not consent to the cession

of territory that Charles demanded,77 and then went to his manor of Berkhampstead, ruined alike in health and in fortune.

On his return to England the prince was probably at once recognised as the natural opponent of the influence exercised by the

anti-clerical and Lancastrian party, and it is evident that the clergy trusted him; for on 2 May he met the convocation of

Canterbury at the Savoy, and persuaded them to make an exceptionally large grant.78 His health now began to

improve, and in August 1372 he sailed with his father to the relief of Thouars; but the fleet never reached the French coast.

On 5 Oct. he resigned the principality of Aquitaine and Gascony, giving as his reason that its revenues were no longer

sufficient to cover expenses, and acknowledging his resignation in the parliament of the next month. At the conclusion of this

parliament, after the knights had been dismissed, he met the citizens and burgesses 'in a room near the white chamber,' and

prevailed on them to extend the customs granted the year before for the protection of merchant shipping for another year.79

It is said that after Whitsunday (20 May) 1374 the prince presided at a council of prelates and nobles held at Westminster to

answer a demand from Gregory XI for a subsidy to help him against the Florentines. The bishops after hearing the pope's letter,

which asserted his right as lord spiritual, and, by the grant of John, lord in chief, of the kingdom, declared that 'he was

lord of all.' The cause of the crown, however, was vigorously maintained, and the prince, provoked at the hesitation of

Archbishop Wittlesey, spoke sharply to him, and at last told him that he was an ass. The bishops gave way, and it was declared

that John had no power to bring the realm into subjection.80

The prince's sickness again became very heavy, though when the 'Good parliament' met on 28 April 1376

he was looked upon as the chief support of the commons in their attack on the abuses of the administration, and evidently acted

in concert with William of Wykeham in opposing the influence of Lancaster and the disreputable clique of

courtiers who upheld it, and he had good cause to fear that his brother's power would prove dangerous to the prospects of his son

Richard [future Richard II].81 Richard Lyons, the king's financial agent, who was impeached

for gigantic frauds, sent him a bribe of £1,000 and other gifts, but he refused to receive it, though he afterwards said that

it was a pity he had not kept it, and sent it to pay the soldiers who were fighting for the kingdom.82

From the time that the parliament met he knew that he was dying, and was much in prayer, and did many good and charitable works.

His dysentery became very violent, and he often fainted from weakness, so that his household believed that he was actually dead.

Yet he bore all his sufferings patiently, and 'made a very noble end, remembering God his Creator in his heart,' and bidding his

people pray for him.83 He gave gifts to all his servants, and took leave of the king his father, asking him three

things, that he would confirm his gifts, pay his debts quickly out of his estate, and protect his son Richard. These things the

king promised. Then he called his young son to him, and bound him under a curse not to take away the gifts he had bestowed. Shortly

before he died Sir Richard Stury, one of the courtiers of Lancaster's party, came to see him. The prince reproached him bitterly

for his evil deeds. Then his strength failed.

In his last moments he was attended by the Bishop of Bangor, who urged him to ask forgiveness of God and of all those whom he had

injured. For a while he would not do this, but at last joined his hands and prayed that God and man would grant him pardon, and

so died in his forty-sixth year. His death took place at the palace of Westminster84 on 8 July, Trinity Sunday, a day

he had always kept with special reverence.85 He was buried with great state in Canterbury Cathedral on 29 Sept., and

the directions contained in his will were followed at his funeral, in the details of his tomb, and in the famous epitaph placed

upon it. Above it still hang his surcoat, helmet, shield, and gauntlets.*

He had two sons by his wife Joan: Edward, born at Angoulême on 27 July 1364 (Eulogium),

1365 (Murimuth), or 1363 (Froissart), died immediately before his father's return to England in January 1371, and was buried in

the church of the Austin Friars, London;86 and Richard, who succeeded his

grandfather on the throne; and it is said, two bastard sons, Sir John Sounder and Sir Roger Clarendon.

1 Fœdera, ii. 798, 811.

2 p. 822.

3 Courthope, p. 9.

4 Fœdera, ii. 880.

5 ib. p. 919.

6 Holinshed.

7 Fœdera, ii. 1049, 1125, 1212.

8 ib. ii. 1083, iii. 32, 35.

9 ib. iii. 84.

10 ib. p. 90; letter of Edward III to Archbishop of York, Retrospective Review, i. 119; Rot. Parl. iii. 163; Chandos, l. 145.

11 Baker, p. 167.

12 Histoire des mayeurs d'Abbeville, p. 328.

13 Baron Seymour de Constant, Bataille de Crécy, ed. 1846; Louander, Histoire d'Abbeville; Archæologia, xxviii. 171.

14 Collectanea, ed. Hearne, 1774, ii. 307.

15 ib. pp. 471-99.

16 Edited by Halliwell for the Camden Society, and also printed in a modernised text in 'Chron. of the White Rose,' pp. 101 sq.

17 Chronicle, p. 324, printed 1569.

18 iii. 348, b. 20.

19 Chroniques d'Engleterre, t. i. l. ii. c. 56, Rolls ed. i. 236.

20 Histoire d'Abbeville, p. 230.

21 Nichols, Royal Wills, p. 66.

22 the subject is discussed in Dr. Murray's 'New English Dictionary,' art. 'Black Prince,' pt. iii. col. ii. p. 895; compare the 'Antiquary,' vol. xvii. No. 100, p. 183.

23 Sloane MS. 56, f. 74, 14th cent.

24 See also J. De Arderne, 'Miscellanea medica et chirurgica,' in Sloane MS. 335, f. 68, 14th cent.; but not, as asserted in Notes and Queries, 2nd ser. xi. 293, in Arderne's 'Practice,' Sloane MS. 76, f.61, written in English 15th cent.

25 Poem in Baron Reiffenburg's BARANTE, Ducs de

Bourgogne; Olivier de Vrée, Généalogie des Comtes de Flandre, pp. 65-7.

26 Archeologia, xxix. 32-59.

27 ib. xxxi. 361.

28 ib. 354-79.

29 Archeologia, xxxi. 381.

30 ib. xxxii. 69.

31 Knighton in Twysden's Decem Scriptores, c.2595.

32 Froissart, iv. 82.

33 ib. p. 95; Nicolas, Royal Navy, ii. 112.

34 Knighton, c.2606; Monasticon, v. 626, 704; Barnes, p. 468.

35 Fœdera, iii. 302, 312.

36 Avesbury, p. 201.

37 Froissart, iv. 163, 373.

38 Jehan le Bel, ii. 188; Froissart, iv. 165.

39 Avesbury, p. 215.

40 Letter of Sir John Wingfield, Avesbury, p. 222.

41 Another letter of Sir J. Wingfield, ib. p. 224.

42 Letter of the prince dated 20 Oct., Archæologia, i. 212; Froissart, iv. 196.

43 For itinerary of this expedition see Eulogium, iii. 215 sq.

44 Chronique de Bertrand du Guesclin, p. 7.

45 Froissart, v. 29; Matt. Villani, vii. c.16.

46 Froissart, v. 64, 288.

47 (Knighton, c.2615; Eulogium, iii. 227; Walsingham, i. 283; Fœdera, iii. 348.

48 As Froissart, v. 82.

49 Matt. Villani, vii. c. 66.

50 Barnes, p. 564.

51 Fœdera, iii. 445.

52 ib. iii. 486; Chandos, l. 1539.

53 James, ii. 223 n..

54 Froissart, vi. 24.

55 Fœdera, iii. 626.

56 Froissart, vi. 275, Amiens.

57 Fœdera, iii. 667.

58 Froissart, vi. 82.

59 Fœdera, iii. 779.

60 Froissart, vi. 183.

61 Fœdera, iii. 754.

62 ib. iii. 799-807.

63 ib. p. 787.

64 Ayala; Chandos.

65 Ayala, xviii. 2.

66 Froissart, vii. 10.

67 Ayala, xviii. c. 23; Froissart, vii. 37; Chandos, l. 3107 sq.; Du Guesclin, p.49).

68 Ayala.

69 Fœdera, iii. 825.

70 Knighton, c. 2629.

71 Walsingham, i. 305.

72 Chandos, l. 3670sq.

73 Froissart, i. 548 n., Buchon.

74 Froissart, vii. Pref p. lviii.

75 Chandos, l. 4043.

76 Froissart, i. 620, Buchon; Cont. Murimuth, p. 209.

77 Fœdera, iii. 907.

78 Wilkins, Concilia, iii. 91.

79 Rot. Parl. ii. 310; Hallam, Const. Hist. iii. 47.

80 Cont. Eulogium, iii. 337. This story, told at length by the continuator of the 'Eulogium,' presents some difficulties, and the pope's pretension to sovereignty and the answer that was decided on read like echoes of the similar incidents in 1366.

81 Chron. Angli&ae;, Pref. xxix, pp. 74, 75, 393.

82 ib. p. 80.

83 ib. p. 88; Chandos, l. 4133.

84 Walsingham, i. 321; Froissart, i. 706, Buchon; it is asserted by Caxton, in his continuation of the 'Polychronicon,' cap. 8, that the prince died in his manor of Kennington, and that his body was brought to Westminster.

85 Chandos, l. 4201.

86 Weever, Funeral Monuments, p. 419.

* [AJ Note: They have since been replaced by replicas.]

Excerpted from:

Dictionary of National Biography. Vol. XVII. Leslie Stephen, ed.

New York: The Macmillan Co., 1889. 90-101.

Other Local Resources:

Books for further study:

Barber, Richard. Edward, Prince of Wales and Aquitaine:

A Biography of the Black Prince.

Boydell Press, 2007.

Barber, Richard. The Life and Campaigns of the Black Prince: from contemporary

letters, diaries and chronicles, including Chandos Herald's Life of the Black Prince.

Boydell Press, 2003.

Chandos Herald. Chivalrous Conqueror: Chandos Herald's Biography of the Black Prince.

Francisque-Michel, trans.

Chivalry Bookshelf, 2005.

Available free at Google Books

Green, David. Edward the Black Prince: Power in Medieval Europe.

Longman, 2007.

Hoskins, Peter. In the Steps of the Black Prince: The Road to Poitiers, 1355-1356.

Boydell & Brewer, 2013.

Jones, Michael. The Black Prince.

Pegasus Books, 2019.

Rogers, Clifford J. The Wars of Edward III: Sources and Interpretations.

Boydell Press, 2000.

Seward, Desmond. The Hundred Years War: The English in France 1337-1453.

Penguin, 1999.

Waugh, Scott L. England in the Reign of Edward III.

Cambridge University Press, 2007.

Edward, the Black Prince of Wales, on the Web:

| to Hundred Years' War

|

| to King Edward III

|

| to King Richard II

|

| to Luminarium Encyclopedia |

Site ©1996-2023 Anniina Jokinen. All rights reserved.

This page was created on April 30, 2007. Last updated March 4, 2023.

|

Index of Encyclopedia Entries:

Medieval Cosmology

Prices of Items in Medieval England

Edward II

Isabella of France, Queen of England

Piers Gaveston

Thomas of Brotherton, E. of Norfolk

Edmund of Woodstock, E. of Kent

Thomas, Earl of Lancaster

Henry of Lancaster, Earl of Lancaster

Henry of Grosmont, Duke of Lancaster

Roger Mortimer, Earl of March

Hugh le Despenser the Younger

Bartholomew, Lord Burghersh, elder

Hundred Years' War (1337-1453)

Edward III

Philippa of Hainault, Queen of England

Edward, Black Prince of Wales

John of Eltham, Earl of Cornwall

The Battle of Crécy, 1346

The Siege of Calais, 1346-7

The Battle of Poitiers, 1356

Lionel of Antwerp, Duke of Clarence

John of Gaunt, Duke of Lancaster

Edmund of Langley, Duke of York

Thomas of Woodstock, Gloucester

Richard of York, E. of Cambridge

Richard Fitzalan, 3. Earl of Arundel

Roger Mortimer, 2nd Earl of March

The Good Parliament, 1376

Richard II

The Peasants' Revolt, 1381

Lords Appellant, 1388

Richard Fitzalan, 4. Earl of Arundel

Archbishop Thomas Arundel

Thomas de Beauchamp, E. Warwick

Robert de Vere, Earl of Oxford

Ralph Neville, E. of Westmorland

Thomas Mowbray, Duke of Norfolk

Edmund Mortimer, 3. Earl of March

Roger Mortimer, 4. Earl of March

John Holland, Duke of Exeter

Michael de la Pole, E. Suffolk

Hugh de Stafford, 2. E. Stafford

Henry IV

Edward, Duke of York

Edmund Mortimer, 5. Earl of March

Henry Percy, Earl of Northumberland

Sir Henry Percy, "Harry Hotspur"

Thomas Percy, Earl of Worcester

Owen Glendower

The Battle of Shrewsbury, 1403

Archbishop Richard Scrope

Thomas Mowbray, 3. E. Nottingham

John Mowbray, 2. Duke of Norfolk

Thomas Fitzalan, 5. Earl of Arundel

Henry V

Thomas, Duke of Clarence

John, Duke of Bedford

Humphrey, Duke of Gloucester

John Talbot, Earl of Shrewsbury

Richard, Earl of Cambridge

Henry, Baron Scrope of Masham

William de la Pole, Duke of Suffolk

Thomas Montacute, E. Salisbury

Richard Beauchamp, E. of Warwick

Henry Beauchamp, Duke of Warwick

Thomas Beaufort, Duke of Exeter

Cardinal Henry Beaufort

John Beaufort, Earl of Somerset

Sir John Fastolf

John Holland, 2. Duke of Exeter

Archbishop John Stafford

Archbishop John Kemp

Catherine of Valois

Owen Tudor

John Fitzalan, 7. Earl of Arundel

John, Lord Tiptoft

Charles VII, King of France

Joan of Arc

Louis XI, King of France

Charles the Bold, Duke of Burgundy

The Battle of Agincourt, 1415

The Battle of Castillon, 1453

The Wars of the Roses 1455-1485

Causes of the Wars of the Roses

The House of Lancaster

The House of York

The House of Beaufort

The House of Neville

The First Battle of St. Albans, 1455

The Battle of Blore Heath, 1459

The Rout of Ludford, 1459

The Battle of Northampton, 1460

The Battle of Wakefield, 1460

The Battle of Mortimer's Cross, 1461

The 2nd Battle of St. Albans, 1461

The Battle of Towton, 1461

The Battle of Hedgeley Moor, 1464

The Battle of Hexham, 1464

The Battle of Edgecote, 1469

The Battle of Losecoat Field, 1470

The Battle of Barnet, 1471

The Battle of Tewkesbury, 1471

The Treaty of Pecquigny, 1475

The Battle of Bosworth Field, 1485

The Battle of Stoke Field, 1487

Henry VI

Margaret of Anjou

Richard Plantagenet, Duke of York

Edward IV

Elizabeth Woodville

Richard Woodville, 1. Earl Rivers

Anthony Woodville, 2. Earl Rivers

Jane Shore

Edward V

Richard III

George, Duke of Clarence

Ralph Neville, 2. Earl of Westmorland

Richard Neville, Earl of Salisbury

Richard Neville, Earl of Warwick

Edward Neville, Baron Bergavenny

William Neville, Lord Fauconberg

Robert Neville, Bishop of Salisbury

John Neville, Marquis of Montagu

George Neville, Archbishop of York

John Beaufort, 1. Duke Somerset

Edmund Beaufort, 2. Duke Somerset

Henry Beaufort, 3. Duke of Somerset

Edmund Beaufort, 4. Duke Somerset

Margaret Beaufort

Edmund Tudor, Earl of Richmond

Jasper Tudor, Earl of Pembroke

Humphrey Stafford, D. Buckingham

Henry Stafford, Duke of Buckingham

Humphrey Stafford, E. of Devon

Thomas, Lord Stanley, Earl of Derby

Sir William Stanley

Archbishop Thomas Bourchier

Henry Bourchier, Earl of Essex

John Mowbray, 3. Duke of Norfolk

John Mowbray, 4. Duke of Norfolk

John Howard, Duke of Norfolk

Henry Percy, 2. E. Northumberland

Henry Percy, 3. E. Northumberland

Henry Percy, 4. E. Northumberland

William, Lord Hastings

Henry Holland, Duke of Exeter

William Fitzalan, Earl of Arundel

William Herbert, 1. Earl of Pembroke

John de Vere, 12th Earl of Oxford

John de Vere, 13th Earl of Oxford

Thomas de Clifford, 8. Baron Clifford

John de Clifford, 9. Baron Clifford

John Tiptoft, Earl of Worcester

Thomas Grey, 1. Marquis Dorset

Sir Andrew Trollop

Archbishop John Morton

Edward Plantagenet, E. of Warwick

John Talbot, 2. E. Shrewsbury

John Talbot, 3. E. Shrewsbury

John de la Pole, 2. Duke of Suffolk

John de la Pole, E. of Lincoln

Edmund de la Pole, E. of Suffolk

Richard de la Pole

John Sutton, Baron Dudley

James Butler, 5. Earl of Ormonde

Sir James Tyrell

Edmund Grey, first Earl of Kent

George Grey, 2nd Earl of Kent

John, 5th Baron Scrope of Bolton

James Touchet, 7th Baron Audley

Walter Blount, Lord Mountjoy

Robert Hungerford, Lord Moleyns

Thomas, Lord Scales

John, Lord Lovel and Holand

Francis Lovell, Viscount Lovell

Sir Richard Ratcliffe

William Catesby

Ralph, 4th Lord Cromwell

Jack Cade's Rebellion, 1450

Tudor Period

King Henry VII

Queen Elizabeth of York

Arthur, Prince of Wales

Lambert Simnel

Perkin Warbeck

The Battle of Blackheath, 1497

King Ferdinand II of Aragon

Queen Isabella of Castile

Maximilian I, Holy Roman Emperor

King Henry VIII

Queen Catherine of Aragon

Queen Anne Boleyn

Queen Jane Seymour

Queen Anne of Cleves

Queen Catherine Howard

Queen Katherine Parr

King Edward VI

Queen Mary I

Queen Elizabeth I

Henry Fitzroy, Duke of Richmond

Margaret Tudor, Queen of Scotland

James IV, King of Scotland

The Battle of Flodden Field, 1513

James V, King of Scotland

Mary of Guise, Queen of Scotland

Mary Tudor, Queen of France

Louis XII, King of France

Francis I, King of France

The Battle of the Spurs, 1513

Field of the Cloth of Gold, 1520

Charles V, Holy Roman Emperor

Eustace Chapuys, Imperial Ambassador

The Siege of Boulogne, 1544

Cardinal Thomas Wolsey

Archbishop Thomas Cranmer

Thomas Cromwell, Earl of Essex

Thomas, Lord Audley

Thomas Wriothesley, E. Southampton

Sir Richard Rich

Edward Stafford, D. of Buckingham

Thomas Howard, 2nd Duke of Norfolk

Thomas Howard, 3rd Duke of Norfolk

John Dudley, Duke of Northumberland

Charles Brandon, Duke of Suffolk

Thomas Boleyn, Earl of Wiltshire

George Boleyn, Viscount Rochford

John Russell, Earl of Bedford

Thomas Grey, 2. Marquis of Dorset

Henry Grey, D. of Suffolk

Charles Somerset, Earl of Worcester

George Talbot, 4. E. Shrewsbury

Francis Talbot, 5. E. Shrewsbury

Henry Algernon Percy,

5th Earl of Northumberland

Henry Algernon Percy,

6th Earl of Northumberland

Ralph Neville, 4. E. Westmorland

Henry Neville, 5. E. Westmorland

William Paulet, Marquis of Winchester

Sir Francis Bryan

Sir Nicholas Carew

John de Vere, 15th Earl of Oxford

John de Vere, 16th Earl of Oxford

Thomas Seymour, Lord Admiral

Edward Seymour, Protector Somerset

Margaret Pole, Countess of Salisbury

Henry Pole, Lord Montague

Sir Geoffrey Pole

Thomas Manners, Earl of Rutland

Henry Manners, Earl of Rutland

Henry Bourchier, 2. Earl of Essex

Robert Radcliffe, 1. Earl of Sussex

Henry Radcliffe, 2. Earl of Sussex

George Hastings, Earl of Huntingdon

Henry Courtenay, Marquis of Exeter

George Neville, Baron Bergavenny

Sir Edward Neville

William, Lord Paget

William Sandys, Baron Sandys

William Fitzwilliam, E. Southampton

Sir Anthony Browne

Sir Thomas Wriothesley

Sir William Kingston

George Brooke, Lord Cobham

Sir Richard Southwell

Thomas Fiennes, 9th Lord Dacre

Sir Francis Weston

Henry Norris

Lady Jane Grey

Sir Thomas Arundel

Sir Richard Sackville

Sir William Petre

Sir John Cheke

Walter Haddon, L.L.D

Sir Peter Carew

Sir John Mason

Nicholas Wotton

John Taylor

Sir Thomas Wyatt, the Younger

Cardinal Lorenzo Campeggio

Cardinal Reginald Pole

Stephen Gardiner, Bishop of Winchester

Edmund Bonner, Bishop of London

Nicholas Ridley, Bishop of London

John Hooper, Bishop of Gloucester

John Aylmer, Bishop of London

Thomas Linacre

William Grocyn

Archbishop William Warham

Cuthbert Tunstall, Bishop of Durham

Richard Fox, Bishop of Winchester

Edward Fox, Bishop of Hereford

Pope Julius II

Pope Leo X

Pope Clement VII

Pope Paul III

Pope Pius V

Pico della Mirandola

Desiderius Erasmus

Martin Bucer

Richard Pace

Christopher Saint-German

Thomas Tallis

Elizabeth Barton, the Nun of Kent

Hans Holbein, the Younger

The Sweating Sickness

Dissolution of the Monasteries

Pilgrimage of Grace, 1536

Robert Aske

Anne Askew

Lord Thomas Darcy

Sir Robert Constable

Oath of Supremacy

The Act of Supremacy, 1534

The First Act of Succession, 1534

The Third Act of Succession, 1544

The Ten Articles, 1536

The Six Articles, 1539

The Second Statute of Repeal, 1555

The Act of Supremacy, 1559

Articles Touching Preachers, 1583

Queen Elizabeth I

William Cecil, Lord Burghley

Robert Cecil, 1st Earl of Salisbury

Sir Francis Walsingham

Sir Nicholas Bacon

Sir Thomas Bromley

Robert Dudley, Earl of Leicester

Ambrose Dudley, Earl of Warwick

Henry Carey, Lord Hunsdon

Sir Thomas Egerton, Viscount Brackley

Sir Francis Knollys

Katherine "Kat" Ashley

Lettice Knollys, Countess of Leicester

George Talbot, 6. E. of Shrewsbury

Elizabeth, Countess of Shrewsbury

Gilbert Talbot, 7. E. of Shrewsbury

Sir Henry Sidney

Sir Robert Sidney

Archbishop Matthew Parker

Walter Devereux, 1st Earl of Essex

Robert Devereux, 2nd Earl of Essex

Penelope Devereux, Lady Rich

Sir Christopher Hatton

Edward Courtenay, E. Devonshire

Edward Manners, 3rd Earl of Rutland

Thomas Radcliffe, 3. Earl of Sussex

Henry Radcliffe, 4. Earl of Sussex

Robert Radcliffe, 5. Earl of Sussex

William Parr, Marquis of Northampton

Henry Wriothesley, 2. Southampton

Henry Wriothesley, 3. Southampton

Charles Neville, 6. E. Westmorland

Thomas Percy, 7. E. Northumberland

Henry Percy, 8. E. Northumberland

Henry Percy, 9. E. Nothumberland

William Herbert, 1. Earl of Pembroke

Charles, Lord Howard of Effingham

Thomas Howard, 4th Duke of Norfolk

Henry Howard, 1. Earl of Northampton

Thomas Howard, 1. Earl of Suffolk

Henry Hastings, 3. E. of Huntingdon

Edward Manners, 3rd Earl of Rutland

Roger Manners, 5th Earl of Rutland

Francis Manners, 6th Earl of Rutland

Henry FitzAlan, 12. Earl of Arundel

Thomas, Earl Arundell of Wardour

Edward Somerset, E. of Worcester

William Davison

Sir Walter Mildmay

Sir Ralph Sadler

Sir Amyas Paulet

Gilbert Gifford

Anthony Browne, Viscount Montague

François, Duke of Alençon & Anjou

Mary, Queen of Scots

Henry Stuart, Lord Darnley

James Hepburn, Earl of Bothwell

Anthony Babington and the Babington Plot

John Knox

Philip II of Spain

The Spanish Armada, 1588

Sir Francis Drake

Sir John Hawkins

William Camden

Archbishop Whitgift

Martin Marprelate Controversy

John Penry (Martin Marprelate)

Richard Bancroft, Archbishop of Canterbury

John Dee, Alchemist

Philip Henslowe

Edward Alleyn

The Blackfriars Theatre

The Fortune Theatre

The Rose Theatre

The Swan Theatre

Children's Companies

The Admiral's Men

The Lord Chamberlain's Men

Citizen Comedy

The Isle of Dogs, 1597

Common Law